The Development of the Tank in Britain.

Mark V Tank at Tank Corps Driving School

<http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205071473 >

The trench deadlock on the Western Front brought to the fore the best technical and theoretical minds in Britain. The various technical arms of Britain’s war establishment pursued radical technological innovations to overcome the “learning curve” of machine warfare. Perhaps no subject outside of the genesis of strategic bombing is as controversial or little understood as the origin of the tank during the First World War.

Castaldi, Fontana, and Nuvolari (2009) in their analysis of tank technology development, define the armoured fighting vehicle as “in most general terms: mobility, firepower and protection”.[1] They defer to Guderian as the doctrinal innovator responsible for the “new tactics based on speed and mobility.”[2]

Castaldi, Fontana, and Nuvolari appreciate technological paradigms as sets of “heuristics” or prevailing descriptions for problem solutions.[3] Modern tank capabilities are understood in terms of their applicability to strategic, operational and tactical situations.

Essentials of Tank Capability.[4]

In material terms, the essence of the problem of the trench deadlock can be expressed by the statistic that 50 infantrymen firing 10 rounds a minute equaled one water-cooled Maxim machine gun at 500 rounds per minute.[5] With the introduction of heavy artillery it likewise became necessary to abandon surprise, as concentrations of artillery required large logistics networks. Furthermore, the heavy artillery bombardments of set-piece battles invariably ruined the landscape. The influence of infantry cannon and direct-fire was reduced in proportion to the expanded role of the heavy artillery.

To return mobility, surprise and direct fire support to the infantry attack, the notion of the armed and armoured vehicle became central. French and British firms independently began to investigate the concept after the initial phase of the war in Autumn of 1914.[6]

The first movements in the direction of an armoured fighting vehicle, naturally enough, came from the fertile mind of H. G. Wells, who had imagined similar machines in 1903.[7]

Holt tractor (75hp) with 8 inch howitzer

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205269802

The basic principle according to Heinz Guderian, was the Holt Caterpillar: a machine, once armed, capable of crossing the deadly no-man’s land despite echelon machine-gun fire, barb wire and the storm of steel – the artillery barrage. Such a machine would have “the potential to crush obstacles, cross trenches and convey its armament under bullet-proof protection into the very midst of the enemy, where it could annihilate the otherwise almost invulnerable machine-guns, and enable one’s own infantry to pass open ground without incurring intolerable casualties.” [8]

Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, appreciated the problem of deadlock from his usual material perspective. The essence of the problem was the same on land as it was on sea. The problem was protection: men from bullets and ships from torpedoes. “Reduced to its rudiments, it consisted in interposing a thin plate of steel between the side of the ship and the approaching torpedo, or between the body of a man and the approaching bullet.”[9] Or, “the Tank was the beginning of the bullet-proof army.”[10]

RNAS Armoured car section entrained, Eastern Front.

< http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205317703>

In Churchill’s vision of the new methods, armored cars operated by the Royal Naval Air Service would “protect the advanced bases which our naval aeroplanes might require to use.”[11]

The exploits of Charles Samson during operations at Dunkirk on one of these missions are legendary.[12] However, they were not to be the norm on the Western Front once the trench lines solidified by the end of October 1914 (the Eastern Front is another story). A new machine was required for surmounting the trenches.

Churchill was unambiguous that it was the RNAS (Royal Naval Air Service) that first embodied the principles that led to the development of the tank: “The armoured car was the child of the air; and the Tank its grandchild.” Churchill also credited the siege howitzer invention of Rear-Admiral Reginald Bacon and the Coventry Ordnance Works, an idea, backed by Field Marshal Lord Kitchener (Minister for War), that would have deployed 15-inch siege howitzers propelled by caterpillar tracks.[13]

Asked for designs that would cross trenches, Bacon prepared a bridging machine, and Churchill prepared to display the idea to Sir John French and Lord Kitchener.[14] The plan was arranged in November 1914, and was tested by the War Office in May 1915, although the machine was rejected as unsatisfactory.[15] Churchill distinguished these first efforts from the independent efforts of Hankey and Swinton.[16]

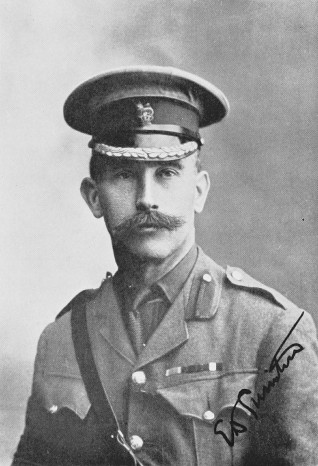

Swinton

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:E._D._Swinton_op._p._81.jpg

Colonel Swinton developed the idea of an armoured fighting vehicle during his reporting as “Eyewitness” a war correspondent for Kitchener.[17] Swinton had been a first hand witness to the utility of armoured warfare as a member of Samson’s RNAS armoured car squadron during the Dunkirk operations.[18] Swinton, who was also assistant secretary to the CID (Committee of Imperial Defence) since 1913, was in close contact with Maurice Hankey, the CID permanent secretary.[19]

The Imperial War Cabinet, May 1917.

Hankey, with other members of the secretariat, is in the back row, third from right. First Sea Lord Jellicoe is second from left, back row, with First Lord Carson to his left. The primaries are seated front, including Lord Milner, DLG, Bonar-Law, Robert Borden, and Jan Smuts

< http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205124978>

Hankey wrote a letter to Historian and tank proponent Sir Basil Liddell Hart on 3 April 1948, in which he explained Swinton’s contribution.[20]

Hankey explained that he and Swinton first germinated the idea when they met at the CID on 20 October 1914. There Swinton noted the existence of the Holt tractor and the use that could be made of it to break the deadlock.[21] Hankey and Swinton, aware of the bureaucratic opposition their agenda would encounter, agreed to make three separate avenues of approach: Hankey at the War Office, Swinton with the General Staff and Captain T. G. Tulloch (RA) with technical matters and execution.[22]

Painting of Horatio Kitchener 1911

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/5346

Guderian relates that Hankey contacted Asquith to follow up on Hankey’s “Boxing Day Memo” (actually dated 28 December 1914). The memo included a proposal for the construction of “large, heavy rollers, themselves bullet proof… with ‘caterpillar’ driving gear… [and] a Maxim gun fitted.”[23]

As Guderian understood the memo, it emphasized the necessity of building “armoured machine-gun carriers with caterpillar tracks.”[24] Guderian critiqued Lord Kitchener for suppressing this early “machine-gun destroyer” initiative.[25]

Indeed, this was the case for Hankey’s approach through the War Office. Although backed by former PM Arthur Balfour (after the May Crisis, First Lord of the Admiralty), and with Asquith showing support, Kitchener detracted from the idea arguing on the case of vulnerability of the tractors to artillery.[26]

Reading Hankey’s December 1914 memo brought Churchill’s mind back around to the machines, and he wrote a letter to Asquith endorsing Hankey’s recommendations.[27]

In that letter, Churchill stated that in December 1914 he had ordered “the Naval Air Service” (RNAS) to build twenty “shields on wheels” for experimental purposes.[28]

Churchill stated that Asquith showed the letter to Kitchener, who received it favourably, but placed further investigation under the responsibility of the Department of the Master General of the Ordnance, which, already dealing with a munitions shortage (the Shell Crisis) failed to move forward with the project.[29]

Feeling that things were not progressing as required, Churchill, on 19 January 1915, instructed Murray Sueter, Director Admiralty Air Department (Churchill calls this the “Air Division”) and chief of the RNAS, to “make certain experiments” with machines designed for defeating trench works.[30]

Sueter, along with his crack armoured car and airplane engineers went to work on the problem. Unfortunately for Sueter, he never received the recognition he thought deserving and when he took the matter directly to King George V, was court martialed by the Admiralty.[31]

Tank designers beside “Mother” at Burton Park, Lincoln. Included are Hetherington, Wilson and Tritton.

< http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205316258>

Churchill met with Major Hetherington, who was working for Sueter as a member of one of the RNAS Armoured Car Squadrons. In conversation with Churchill on 17 February, Hetherington proposed the construction of “land battleships” on a large scale.[32] Churchill forwarded these proposals to First Sea Lord Sir John Fisher, and on 20 February formed the Landship Committee, president Tennyson-d’Eyncourt, the Chief Constructor of the Navy.[33] Churchill’s secret committee, without correspondence with the War Office, produced two variants of machines, one wheeled the other caterpillar driven, the latter which Churchill ordered into production on 26 March 1915.[34]

At the behest of Hankey, the War Office had actually built and tested a small Holt tractor type, in February and March 1915, as related by Chuchill, although it failed to meet expectations.[35]

After the fallout of the May Crisis (collapse of the Fisher-Churchill regime over the Dardanelles campaign), the Landship Committee faced the financial chopping block, and Churchill claims that his personal appeal to Balfour, the incoming First Lord of the Admiralty (as of 25 May 1915) saved the project- trimmed down to a single machine. This single machine eventually became “Mother” which was tested at Lincoln in January and February 1916.[36]

Meanwhile, in June 1915 Swinton brought his proposal to the attention of Field Marshal Sir John French, who passed it to the War Office.[37] It can be seen then that Hankey’s policy of multiple avenues of approach was steadily building pressure.

A more complex machine was put to trial by the Landship Committee in September 1915. This was the “No 1 Lincoln Machine” – known as “Little Willie” after Walter Wilson – which was laid down on 11 August 1915.[38]

“Little Willie” the September 1915 trial machine.

< http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205249606 >

Pressured by Sir John French to investigate Swinton’s proposals, Swinton chaired the two pivotal interdepartmental conferences on 28 August and 24 December, 1915, in which the separate avenues of the Admiralty’s Landship committee and the War Office approach were united.[39] The latter meeting concluded with the placing of an order for fifty machines, which, to ensure secrecy, Swinton coined as “tanks”.[40]

Swinton, who had been at the “Little Willie” trial in September 1915 was in close liaison with the machine’s designers, Sir William Tritton and Walter Wilson. Together they worked up a scheme for a larger machine which was approved for construction by the Landship Committee meeting of 29 September 1915.[41]

“Mother” the prototype tank on trials in January 1916.

< http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205316267>

Hankey and Swinton continued to work closely, and there was speculation that Swinton was being groomed to succeed Hankey as permanent secretary. In February 1916 the new machines were tested. Shortly afterwards, the Heavy Section, Machine Gun Corps was formed, later renamed the Tank Corps in 1917.[42]

“Mother” underwent trials in February 1916 with Kitchener, Balfour and David Lloyd George in attendance. Kitchener apparently held to his position that these new machines would be vulnerable to enemy artillery.[43]

Lloyd George, then Minister of Munitions, was enthusiastic about the machine’s potential, and maneuvered to have the Landship Committee absorbed into his ministry.[44] From there, Lloyd George ordered 100 of the new model, now known as the “Tank Mark I”.[45] The order was shortly increased to 150 machines. The tank, brainchild of the conspiratorial Swinton-Hankey workgroup, grandchild of the Churchill-Sueter-Samson triumvirate, had come of age.

Tank F-10 and soldiers of the “Heavy Section Machine Gun Corps” at Rollencourt Tank Park (“Tankodrome” 30 June 1917.

< http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205236083>

[1] Carolina Castaldi, Roberto Fontana, and Alessandro Nuvolari, “‘Chariots of Fire’: The Evolution of Tank Technology, 1915-1945,” Journal of Evolutionary Economics 19, no. 4 (2009): 546–66. p. 546

[2] Ibid. p. 547

[3] Ibid. p. 547

[4] Ibid. p. 553

[5] Spencer Tucker, Tanks: An Illustrated History of Their Impact, Weapons and Warfare Series 17 (Santa Barbara, California: ABC-Clio, Inc., 2004). p. 6

[6] Ibid. p. 10

[7] Winston Churchill, The World Crisis: 1911-1918, Abridged and Revised Edition (New York: Free Press, 2005). p. 309

[8] Heinz Guderian, Achtung-Panzer!: The Development of Tank Warfare, trans. Christopher Duffy (London: Cassell, 1999). p. 48

[9] Churchill, The World Crisis: 1911-1918. p. 303

[10] Ibid. p. 304

[11] Ibid. p. 304

[12] Charles Rumney Samson, Fights and Flights (Nashville: The Battery Press, 1930). p. 12 et seq.

[13] Churchill, The World Crisis: 1911-1918. p. 305 & Tucker, Tanks: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. p. 11

[14] Churchill, The World Crisis: 1911-1918. p. 305

[15] Ibid. p. 305

[16] Ibid. p. 306

[17] Tucker, Tanks: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. p. 12

[18] Roger Ford, The World’s Great Tanks: From 1916 to the Present Day (Hong Kong: Brown Books, 1997). p. 7

[19] H. C. G. Matthew and B. Harrison, eds., “Swinton, Sir Ernest Dunlop,” The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, September 23, 2004), http://www.oxforddnb.com.proxy.lib.sfu.ca/templates/article.jsp?articleid=36392&back=#cosubject_36392.

[20] Stephen Roskill, Hankey: Man of Secrets, vol. Volume I: 1877–1918, 3 vols. (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1970). p. 147

[21] Ibid. p. 147

[22] Ibid. p. 147

[23] Ibid. p. 148

[24] Guderian, Achtung-Panzer!: The Development of Tank Warfare. p. 48

[25] Ibid. p. 48

[26] Roskill, Hankey: Man of Secrets. p. 147

[27] Churchill, The World Crisis: 1911-1918. p. 306, Roskill, Hankey: Man of Secrets. p. 148

[28] Churchill, The World Crisis: 1911-1918. p. 306-7

[29] Ibid. p. 307

[30] Ibid. p. 307

[31] ADM 178/29

[32] Churchill, The World Crisis: 1911-1918. p. 308

[33] Ibid. p. 308

[34] Ibid. p. 309

[35] Guderian, Achtung-Panzer!: The Development of Tank Warfare. p. 49

[36] Churchill, The World Crisis: 1911-1918. p. 310

[37] Guderian, Achtung-Panzer!: The Development of Tank Warfare. p. 49

[38] Ford, The World’s Great Tanks: From 1916 to the Present Day. p. 9

[39] Tucker, Tanks: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. p. 14

[40] Matthew and Harrison, “Swinton, Sir Ernest Dunlop.”

[41] Ford, The World’s Great Tanks: From 1916 to the Present Day. p. 9

[42] Matthew and Harrison, “Swinton, Sir Ernest Dunlop.”

[43] Guderian, Achtung-Panzer!: The Development of Tank Warfare. p. 50

[44] Ford, The World’s Great Tanks: From 1916 to the Present Day. p. 10

[45] Ibid. p. 10