Breaking the Line: Cavalry Tactics at Balaklava

25 October 1854

“Into the Valley of Death” by John Charlton.1

“Popular history presents the Crimean War as the British army’s most disastrous campaign, with the blundering charge of the Light Brigade and the suffering soldiers at Balaclava saved only by Florence Nightingale.”2

“In English literature the War inspired Tennyson’s ‘Charge of the Light Brigade,’ a poetic description of an episode in the battle of Balaklava. It might be added that this conflict, which is considered by many scholars as unnecessary and a result of misunderstandings, was the more tragic since typhus and other epidemics caused even more deaths than did the actual fighting.”3

The Alliance between Britain and France was formally arranged in March 1854 when the two powers agreed to assist the Ottoman Sultan against the Russian Empire.4 The Allies commenced operations in the Crimea with a 50,000 man expeditionary landing at Balaklava in September 1854, with the intention of securing Sevastopol, Russia’s primary naval base on the Black Sea.5 Due to the introduction of steam transport the expeditionary force’s cavalry contingent arrived in theatre before the fodder for its horses, not to mention tents for the soldiers: the supply train had been dispatched on sailing vessels with resultant delays.6 The Czarist forces in immediate opposition, under Prince Menshikov, were defeated at the Battle of the Alma, 20 September 1854. The Allied guns expended 900 rounds during the Alma.7 In response to this setback, Menshikov retreated to Sevastopol, where as C-in-C, with Gortschakoff as second in command and Chomutoff in command of the artillery he prepared his defences.8 Vice-Admiral Kornilov, who had fought at the Battle of Sinope, 30 November 1853, and was Chief of Staff of the Black Sea Fleet, led the Russian garrison.9

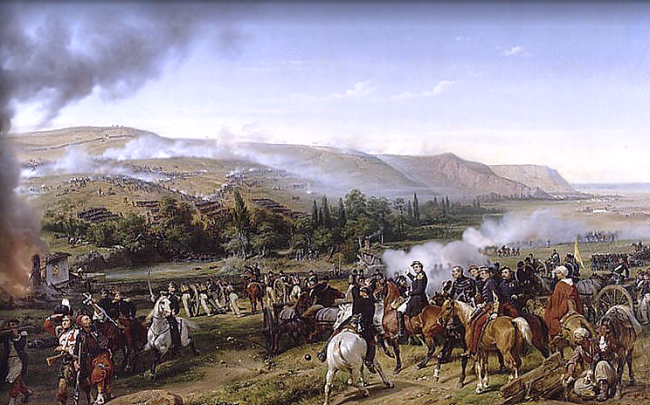

Battle of the Alma, by Horace Vernet.10

In preparation for the siege of Sevastopol the Allies deployed heavy artillery, and by the end of September naval guns and army howitzers were in position on the heights overlooking Balaklava.11 Insufficient logistics resulted in a cholera outbreak that weakened the Allied army throughout the initial phase of the campaign.12

Shipping at Balaklava Harbour, 1855.13

The Russian forces defending Sevastopol were eager to prevent the extended siege of the port and prepared a counter attack of the Allied beach-head. Early in October Russian infantry and artillery moved into position: Brigadier-General Airey, Lord Raglan’s Quartermaster-General,14 spotted a brigade size force, 5,000 men, as they moved towards the Allied positions on 3 October, a report complemented by reconnaissance from the 4th Dragoons that identified 3,500-4,000 cavalry on 7 October.15 The same day, Lord Raglan, General Airey and staff committed to reconnaissance of the Russian positions and a council of war was held in the evening.16 On 10 October four French battalions, 2,400 men, began construction of trenches and redoubts for their cannon to prepare for the siege.17

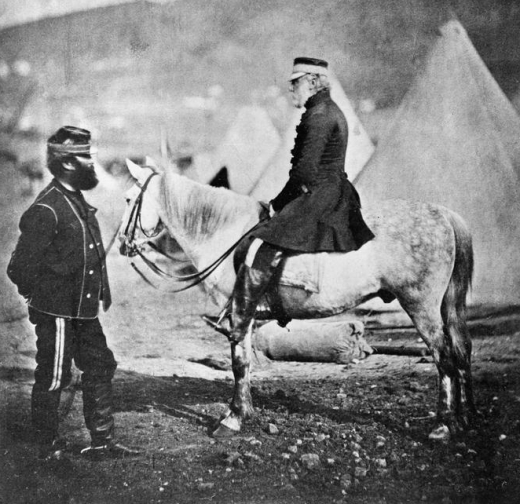

Roger Fenton’s photograph of the Allied commanders: Lord Raglan, Omar Pasha and Marshal Pelissier.18

Allied reinforcements continued to pour in from the beach-head, despite the long range Russian batteries zeroed on the Balaklava approach.19 The British 2nd Division entrenched two miles from Sevastopol, supported by the 4th Division, and covered to the right by the 3rd Division and Light Division (Lt. General Sir George Brown)20 with the 1st Division outside Balaklava, the Royal Marines in garrison at the town itself.21 The Russian lines at this time were permeable, certain Polish soldiers defected and crossed the Allied lines with sensitive information.22

On 17 October Vice-Admiral Kornilov was mortally wounded when the Allied guns, in conjunction with a fleet sortie, bombarded Sevastopol in the opening phase of the siege that was to last for the next 13 months.23 Continuous shelling and skirmishing for the next three days highlighted the strength of Meshikov’s positions. On 20 October reports arrived from England that Sevastopol had fallen, propaganda which “excited great indignation and ludicrous astonishment” from the forces in theatre.24

Positions of Allied forces around Sevastopol, October 1854.25

On 25 October, Menshikov opened his counter-attack with 25,000 men, led by General Pavel Liprandi.26 William Howard Russell, war correspondent for The Times witnessed the battle of Balaklava and provided the account Lord Tennyson used as source material for his renowned poems.27

General Pavel Petrovitch Liprandi28

The morning of 25 October, pursuant to their plan of attack, Russian artillery commenced bombardment of the Allied positions with shell. The Allied batteries at No. 1 redoubt fell and the Turkish gunners retreated, but were run down by Russian cavalry as they withdrew to No. 2 redoubt.29 A Russian cavalry charge carried No. 2 redoubt and the Turkish soldiers continued their retreat towards No. 3 redoubt, only to be likewise overrun. Russian gunners, well practiced in the rapid preparation of batteries,30 immediately secured the Allied batteries stationed in the captured redoubts and turned them against the Allied positions.31 These guns included advanced models capable of firing highly accurate rotating shells prior to the introduction of cannon rifling through a sophisticated ovoid barrel design, later employed against Sevastopol with deadly effect.32 The Turkish batteries abreast the French trenches and Allied naval batteries emplaced on the Balaklava heights ineffectively returned fire.33

The Turkish infantry, armed with the new Minie rifle, reformed when they fell back upon the positions occupied by Britain’s 93rd Highlander regiment. Upon engaging these positions, well formed, the Russian cavalry were forced to halt their advance and deployed at half a mile distance in brigade strength, 3,500 strong in preparation for a decisive charge.34 Opposite the Russian cavalry were the positions held by the 93rd regiment, bayonets fixed in a “thin red streak”- two lines deep- supported by the entire Allied cavalry force: the French cavalry and the British cavalry division under Lord Lucan: Brigadier-General Scarlett’s Heavy Brigade composed of the veteran Scots Greys, Enniskillens, 4th Royal Irish [Dragoon Guards], 5th Dragoon Guards, and 1st Royal Dragoons35 flanked by Lord Cardigan’s Light Brigade (Dragoons, Lancers, Hussars) on the left echelon.36

“Major General George Charles Earl of Lucan, KCB, Commander of the Cavalry Division.”37

Russell vividly described the moments between the formation of the opposing lines, broken by sporadic shell bursts, and the thunderous ensuing charge of the Russian cavalry.38 The Turks fired rifle volleys at 800 and 600 yards.39 At 250 yards the 93rd regiment fired volley, breaking up the Russian charge at close range.40

The initial cavalry charge stopped short, General Liprandi developed a flanking manoeuvre against Raglan’s HQ (defended by the French Zouaves) positioned on the heights overlooking Balaklava. Liprandi planned to use his “corps d’elite- their light blue jackets embroidered with silver lace” for this coup de main.41 Observant of the weakness of the Allied position from his HQ on the heights above the precarious Allied position, Raglan dispatched orders for Lord Lucan to have Scarlett’s Heavy Brigade prepare a counter-charge.42 Russell, with his exclusive report for The Times in mind, watched from Raglan’s HQ as the opposing cavalry forces deployed.

The British charge, in what can only be described as a measure of incredulous courage, began when the “trumpets rang out … through the valley,” as the cavalry with the Greys and Enniskillens at the spear-point charged directly into the mass of veteran Russian cavalry and, with consummate skill, smashed through their lines.43

Tennyson immortalized this moment in his “Charge of the Heavy Brigade”44

Fell like a cannon-shot,

Burst like a thunderbolt,

Crash’d like a hurricane,

Broke thro’ the mass from below,

Drove thro’ the midst of the foe

With this devastating frontal assault underway, the 4th Dragoon Guards and 5th Dragoon Guards swung in from the flanks and completed the route of the Russian cavalry.45 No doubt Cannae was the central thought on Lucan’s mind at this point. Raglan dispatched his aide-de-camp, Lord Curzon, with congratulations- “Well done!”- intended for General Scarlett who had personally led the counter-charge.46 There were 35 British killed and wounded.47

Major General the Hon. Sir James Scarlett, KCB, Commander of the Heavy Cavalry Brigade with Lt. Colonel Alexander Low, 4th Light Dragoons.48

Cardigan was now ordered to recaptured the Allied redoubts, defended by 30 to 40 captured guns.49 Russell described the orders that led to this attack: Brigadier Airey through Captain Nolan of the 15th Hussars, ordered Lucan “to advance” upon the Russian positions.50 Upon receipt of these orders, Lucan asked for clarification, to which Nolan was said to have replied, “’There are the enemy, and there are the guns,’ or words to that effect”.51 Lucan passed the order on to his brother-in-law, Cardigan, and thus Cardigan assumed he was to charge the mile and a half against the Russian cannon positioned in their emplacements. It was not yet 1100 hours.52 Spurred by the decisive victory of the Heavy Brigade, without delay, at 1110 the Light Brigade charged.53

Lord Cardigan recalled the charge in 1855: “We advanced down a gradual descent of more than three-quarters of a mile, with the batteries vomiting forth upon us shells and shot, round and grape, with one battery on our right flank and another on the left, and all the intermediate ground covered with the Russian riflemen; so that when we came to within a distance of fifty yards from the mouths of the artillery which had been hurling destruction upon us, we were, in fact, surrounded and encircled by a blaze of fire, in addition to the fire of riflemen upon our flanks.”54

Lord Cardigan: James Thomas Brudenell.55

Russell editorialized: “Surely that handful [the Light Brigade, 636 men] were not going to charge an army in position? Alas! It was but too true- their desperate valour knew no bounds, and far indeed was it removed from its so-called better part- discretion.”56 The Russian cannon opened fire at 1,200 yards.57 Captain Nolan was killed as he led the first line.58 Riding alongside Nolan was Private James Lamb, 13th Light Dragoons: Lamb described Nolan receiving a mortal wound from one of the first Russian volleys then, still charging, disappeared into the gun smoke.59 The Russian gunners kept up fusillade fire of mixed canister and grape as the Light Brigade galloped in.60 Lamb himself was knocked unconscious and awoke unhorsed and lost in the dense smoke.61

The Allied guns on the Balaklava heights fired counter-battery, although the Light Brigade had already broken through.62 Quoth Tennyson:

Plunged in the battery-smoke

Right thro’ the line they broke;

Cossack and Russian

Reel’d from the sabre-stroke

Shatter’d and sunder’d.63

“Charge of the Light Cavalry Brigade” 1855 Lithographic print.64

Lamb saw Russian infantry forming up from the gun positions to add their rifle fire to the melee. He initially mistook the charge of the French Dragoons (see below) as another flanking attack by Cossacks.65

Russell described the appearance of “a regiment of [Russian] lancers” which counter-attacked at this point, although Colonel Shewell (8th Hussars) seeing the brigade’s exposed flank, immediately charged the approaching enemy.66 During this encounter with unquestionable courage and skill the Russian gunners rallied to the guns and fired grape directly into the general melee: Russell is unambiguous that it was this courageous act by the gunners that broke the Light Brigade.67 Covered by the Heavy Brigade, Cardigan retreated, clearing the guns by 1135. Lucan and Cardigan were both wounded, the latter by lance.68

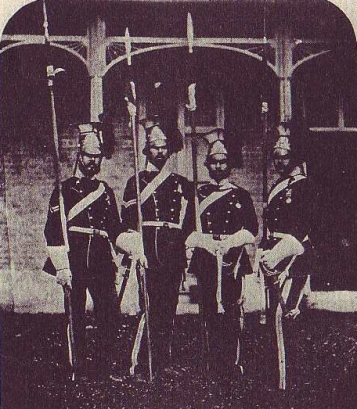

Four survivors from the 17th Lancers.69

Meanwhile, the French cavalry charged the Russian guns firing enfilade on the Light Brigade.70 One of these positions was covered by a regiment of Polish Lancers which the French Dragoons engaged despite suffering terrible casualties from incoming grape and canister.71 The Russian forces began to withdraw from the Allied redoubts: No. 1 was recaptured, and at 1115, as the melee between the Light Brigade and the Russian lancers occurred, No. 2 position was destroyed when the withdrawing Russian forces exploded its magazine.72 No. 3 position was abandoned but with great success as the Russians hauled off seven of the nine Allied guns emplaced there.73 The British had in total 13 officers killed and missing, 156 soldiers killed and missing and 21 officers and 197 men wounded. 520 horses had become casualties.74

Private Lamb’s calvary regiment was decimated, suffering nearly 50% casualties: “we went into action that morning 112 strong and came out with only 61.”75 Lamb, himself wounded, had difficulty returning to the Allied lines and once back found himself reported as killed.76

The Russians celebrated the victory at Sevastopol when the captured guns were added to their armoury. At 2100 a general barrage of the Allied position commenced although without effect.77

The assault of 25 October was followed by a brigade sized attack “4,000 Russians” against the 2nd Division’s position on the British right flank.78 The Russians again attempted to displace the 2nd Division on 5 November resulting in the Battle of Inkerman, a desperate close order affair, which Russell described as “the bloodiest struggle ever witnessed since war cursed the earth.”79

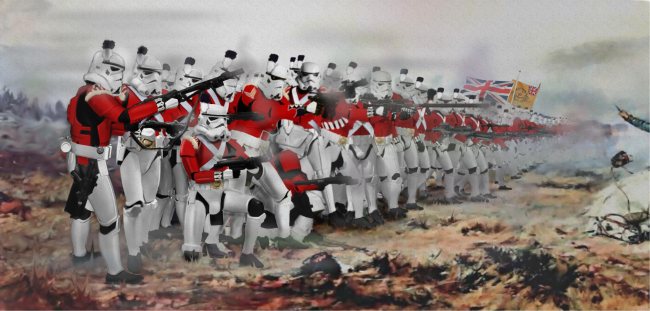

“The Thin Red Line” by Mark Wells <http://www.coroflot.com/mark19/art> satirizing Robert Gibb’s 1881 portrayal80 of the 93rd Highlander Regiment at the “Battle of Balaclava on October 25, 3054… [sic]”81

2 Arthur Herman, To Rule The Waves: How the British Navy Shaped the Modern World, New York: HarperCollins’ Publishers, 2004, p 541

3 Nicholas Riasanovsky and Mark Steinberg, A History of Russia, Seventh Edition, New York: Oxford University Press, 2005, p 316

4 Eric Grove, The Royal Navy Since 1815, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005, p 29

5 F. R. Bridge and Roger Bullen, The Great Powers and the European States System 1814-1914, Second Edition, Toronto: Pearson Education Limited, 2005, p 121

6 Geoffrey Till, Seapower: A Guide for the Twenty-First Century, second edition, Cass Series: Naval Policy and History, New York: Routledge, 2009, p 237; Andrew Lambert and Stephen Badsey, The Crimean War, The War Correspondents, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Bramley Books, 1997, p 90

7 Lambert & Badsey, The Crimean War, p 90

8 Lambert & Badsey, The Crimean War, p 93

9 Lambert & Badsey, The Crimean War, p 96

11 Lambert & Badsey, The Crimean War, p 88, 90

12 Lambert & Badsey, The Crimean War, p 89-90; see also, John Sweetman, “‘Ad Hoc’ Support Services During The Crimean War, 1854-6: Temporary, Ill-Planned and Largely Unsuccessful,” in Military Affairs 52, no. 3 (July 1, 1988): 135

14 Lambert & Badsey, The Crimean War, p

15 Lambert & Badsey, The Crimean War, p 89, 92-3

16 Lambert & Badsey, The Crimean War, p 94

17 Lambert & Badsey, The Crimean War, p 95

19 Lambert & Badsey, The Crimean War, p 90

20 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 6 fn

21 Lambert & Badsey, The Crimean War, p 90

22 Lambert & Badsey, The Crimean War, p 93

23 Lambert & Badsey, The Crimean War, p 96

24 Lambert & Badsey, The Crimean War, p 102

25 Lambert & Badsey, The Crimean War, p 99

26 Lambert & Badsey, The Crimean War, p 103

27 Robert Hill, ed., Tennyson’s Poetry, Second Edition, New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1999, p 307-8, 307 fn.

29 Roger Hudson, ed., William Russell: Special Correspondent of The Times, London: The Folio Society, 1995, p 28

30 Lambert & Badsey, The Crimean War, p 91

31 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 28-9

32 J. F. C. Fuller, The Conduct of War: 1789-1961, New Brunswick, N. J.: Da Capo Press, 1992, p 89 fn

33 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 29

34 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 29

35 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 29

36 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 29

38 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 29

39 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 29

40 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 30

41 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 30

42 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 30

43 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 30-1

45 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 31

46 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 30-1

47 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 31

49 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 31

50 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 31-2

51 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 32

52 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 32

53 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 32

54 John France, Perilous Glory: The Rise of Western Military Power, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011, p 232

56 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 32

57 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 32

58 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 33

59 James Lamb, “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” Strand Magazine: An Illustrated Monthly (July 1891): 348–351

60 Lamb, “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” p 348

61 Lamb, “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” p 348

62 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 33

63 Hill, ed., Tennyson’s Poetry, p 308

64 <http://www.thehistoryblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Charge-of-the-Light-Brigade-lithograph.jpg>

65 Lamb, “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” p 349

66 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 33

67 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 33

68 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 33

69 Hudson, ed., William Russell, between pages 30-31

70 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 33

71 Lamb, “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” p 349

72 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 33

73 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 33

74 Lambert & Badsey, The Crimean War, p 117

75 Lamb, “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” p 350

76 Lamb, “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” p 351

77 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 34

78 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 34

79 Hudson, ed., William Russell, p 34

81 <http://s3images.coroflot.com/user_files/individual_files/original_45080_whgILURoklUO1Ao1p3Ys6tIBk.jpg> See also Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin, The Empire Writes Back: Theory and Practice in Post-colonial Literatures, Routledge, 2002