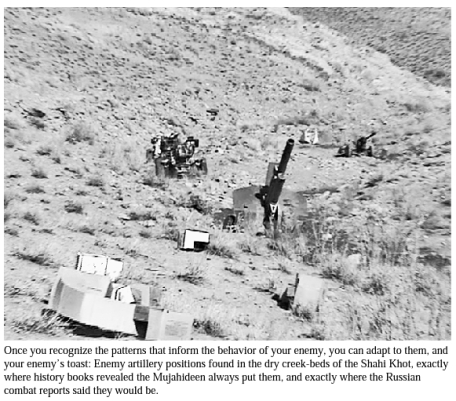

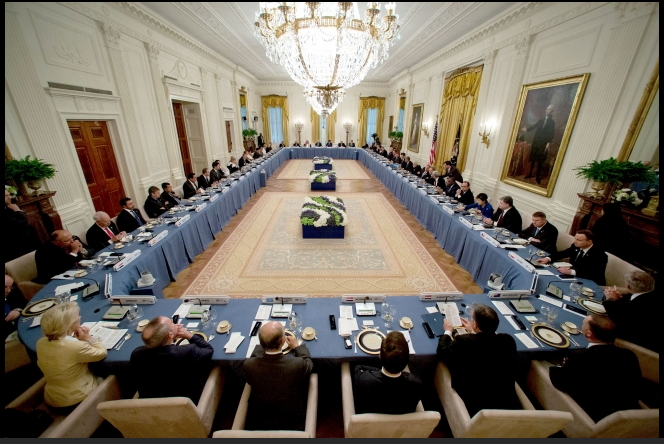

Phormio: The Athenians, & the Origins of the Peloponnesian War (432-427)

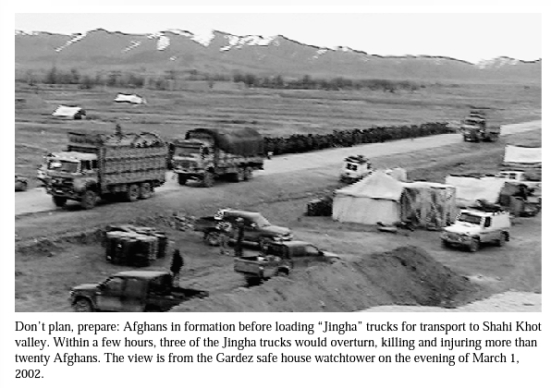

Phormio, son of Asopius, was born circa 480 BC. A recurring character in Thucydides (c. 460-400), Phormio’s career spanned the rise of the Athenian empire and the Peloponnesian Wars (460-445, 432-404). A contemporary of Pericles (495-429), Phormio is known to history primarily for his crushing victories over the Peloponnesians, in the tradition of Themistocles or Cimon, at Naupactuas (modern Lepanto) on the Corinthian Gulf. The relevant background, and Phormio’s involvement in this campaign, are described by Thucydides in Book Two of his History of the Peloponnesian War, and through a collection of fragmentary sources.

Phormio has become a figure of significant historical interest for his role during the first three years of the Great (Second) Peloponnesian War, 431-428, and several scholars have dedicated entire chapters to his exploits.[1] Phormio’s proficiency at maritime warfare, his unconventional tactics, guile, and ability to steal victory from the jaws of defeat, has ensured his legacy in the Western tradition. Phormio’s plaudits from modern historians are many: he has been described as “wily” by Donald Kagan,[2] “an exemplar of Athenian dash and enterprise” and as a commander who “personified the spirit and skill of the Athenian navy,” by H. D. Westlake,[3] and John Hale wrote that Phormio’s “…genius lay in quick improvisation on unexpected themes, and in his conviction that every situation, no matter how discouraging, offered a chance for victory.”[4] Who was this obscure fifth century Athenian?

This post provides the necessary background to contextualize for the modern reader the 5th century struggle between the Athenian empire and the Peloponnesian League, and presents a reconstruction of Phormio’s career, culminating in the battle narrative of his stunning victories in 429.

Athens, Sparta and the Peloponnesian Wars

Bronze statuette of a warrior on horseback, wearing a Corinthian helmet, c. 560-550 BC from Taranto.

“The Greek city-state was a strange little world, very different from the medieval town in western Europe. The latter was quite separate from the countryside: it was self-contained, with political and economic benefit reserved to the privileged townspeople who lived intra muros. The Greek polis on the other hand, while ‘linked to an urban centre, was not identical with it’. The ‘citizens’ were residents of a territory greater than the city itself, which was only one element in the state, though an important one of course, since everyone made use of its market-place or agora, its citadel a place of refuge, and its temple devoted to the divine protector of the polis.”[5]

Classical Hellas was as “a pattern of islands, whether real islands in the sea or ‘islands on dry land’. Each of the Greek city-states occupied a limited terrain, with a few cultivated fields, two or three areas of grazing land for horses, enough vines and olive-groves to get by, some bare mountain slopes inhabited by herds of goats and sheep…”[6]

– Fernand Braudel

Hoplite statue from Dodona, c. 510-500 BC, Berlin Antiquities Collection. Note the Boeotian shield.

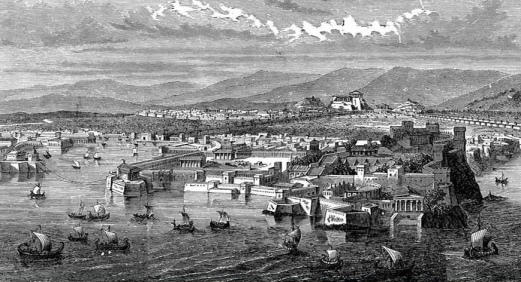

In the decades immediately following the Persian Wars (490-479), the Athenians emerged from the Spartan-led pan-Greek alliance as a thalassocracy, or sea power. Under the able guidance of Themistocles, Cimon, and then Pericles, the Athenians came to dominate the Aegean, and large portions of Boeotia and Thrace. This was an inevitable development for Athens, a city that possessed a dedicated domestic production capacity in the form of metals, marble, ceramics, oil, wine, wool, dye, and textiles,[7] and a sophisticated system of public finance, all gravitating around the unique Athenian democracy.

The large, publicly financed, workforce of slaves and government servants in Athens, and its Aegean periphery, meant that it was imperative to perpetually import foodstuffs, principally grain and fish, to survive.[8] Suppressing piracy, and ensuring the regularity of maritime trade, was therefore a priority for the Athenian navy, which acted as an Aegean police force, and maintained good order at sea.[9]

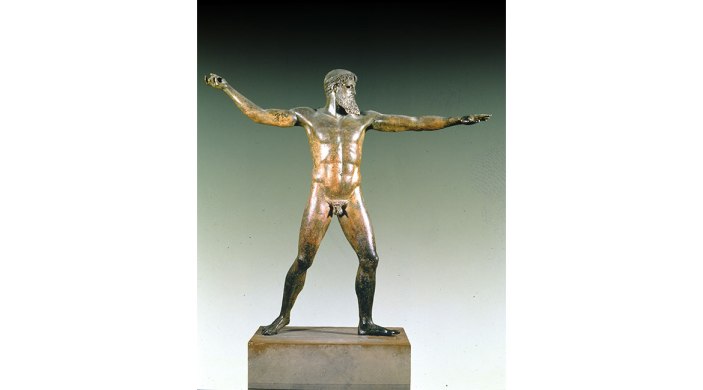

Statue of Zeus or Poseidon, Cape Artemision, Euboea, 460 BC

Themistocles, who destroyed Xerxes’ Phoenician and Egyptian fleet at the Battle of Salamis in 480, cleared the way for Cimon (510-450) to begin expelling the Persians from Thessaly, Thrace and Ionia. Cimon, the son of Miltiades (550-489) who had fought alongside Themistocles and Callimachus at Marathon in 490, launched his aggressive empire-building campaign in 477. The date 477 is significant, as it was at this time that the corruption and excesses of the Spartan general Pausanias caused the first Ionian allies to join Athens in an attempt to break Sparta’s hegemony.[10] Eion fell in 476, and the Athenians gained their first foothold on the Chalcidice peninsula. The war against Persia culminated in the decisive, combined arms, battle of the Eurymedon in 469/6. A major rebellion on Naxos was suppressed in 466, and in 463/2 the Corinthians attacked Megara,the Megarians in turn joining with the Athenians to isolate the Peloponnesians south of the Corinthian isthmus.[11] Cimon, a Spartan sympathizer, was ostracized in 461.

Athenian warship painted on Attic vase c. 520

George Grote considered this opening phase of the Lacedemonian-Athenian competition, 477-450, as a period of rising Athenian hegemony, followed by the transition thereafter to empire: a condition that was ultimately to last until the Athenian navy was defeated by Lysander at the battle of Aegospotami in 405.[12] After the Persian Wars, Sparta was the foremost warrior polis in Hellas, commanding a formidable coalition of Greek allies, including Thebes, Corinth, the islands of Melos and Thera, and later Syracuse.[13] The Spartans were decisively weakened in 464, however, by an earthquake that ruined the polis, killing tens of thousands, and was immediately followed by a serf rebellion amongst the helots.

The First Peloponnesian War (461-446)

Hoplites from Clazomenae sarcophagus

The Athenians took advantage of Sparta’s weakness to launch the First Peloponnesian War.[14] In 459/8 Myronides smashed the Corinthians when they attempted to expel the Athenians from Megara, but the Spartans recovered their position somewhat by defeating the Athenians at Tanagra in 457. This Peloponnesian victory was overawed, however, by the Athenian conquest of Aegina that year, after a spectacular naval battle in which the Athenians captured 70 triremes.

Map of Helles with battles from the Persian Wars (490-479), from Robert Strassler, ed., The Landmark Thucydides (New York: Free Press, 2008 [originally 1996])

Myronides crushed the Boeotian Confederacy at Oenophyta in 456,[16] and the war was temporarily halted as negotiations took place, followed by the return of Cimon, recalled from ostracism, who arranged a five year truce between Athens and Sparta (c. 451/0).[17] The war against the Boeotian Confederacy continued, however, resulting in the Theban victory over Athens at Coroneia in the spring of 446, but was then concluded by Pericles’ recapture of Euboea in July of that year.[18] The Thirty Years’ Peace between Athens and Sparta followed,[19] with the Delian League then, in little more than a decade, securing possession of every island in the Aegean except Thera and Melos.[20] A symbol of the rising Athenian empire, the Delian League’s overflowing treasury of imperial tribute had, of course, been moved from Delos to Athens around 454.[21]

Battles of the First Peloponnesian War, 460-445

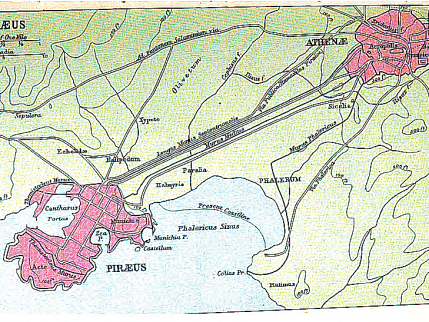

The Delian League was now steadily encroaching on territories controlled by the members of the Peloponnesian League, and the Athenians took appropriate defensive measure.[22] Themistocles, after the Persian sacking of Athens in 479, instituted a defensive rebuilding program during which the city’s walls were repaired and strengthened, and the Piraeus was fortified. In 462 the Athenians began construction on the long walls to unite Athens and the Piraeus into a single fortress,[23] a monumental task completed five years later in 457.[24] In times of crisis – when the Spartans were in Attica – 16,000 men, slightly over half the entire military capacity of Athens, were required to man the metropolis’ walls.[25]

The Athenian polis, and the Delian League, 447-431

The Varvakeion Athena, c. 200-250 AD. A reduction of the 40 foot tall Athena Parthenos by Pheidias that was erected in the Parthenon during 447-438 BC, & modern reconstruction of the ivory and gold statute, from Spivey & Squire, Panorama of the Classical World (2004)

Before Solon’s time, c. 594, and, indeed, with varying degrees of populist reforms since, the citizenry of Athens was composed of essentially a military reserve (“those who provided themselves with arms”), ruled over by a landed aristocracy composed of various tribal elites.[26] The chief offices were those of the archons, representing the ancestral religious and military power of a hereditary state.[27] In 510 the Spartan King Cleomenes overthrew the Athenian tyranny founded by Pisistratus, installing instead a Spartan oligarchy headed by Isagoras. Immediately afterwards, however, the exiled democrat Cleisthenes returned to power and formulated the familiar Athenian constitution of 509/8, reforming the archons into annually elected civic-religious offices with greatly reduced real powers. The ekklesia, the citizen Assembly at the Pnyx, became the new centre of power.[28] This body was composed of all male citizens over the age of twenty, with a quorum of 6,000 required for decisions.[29] The Assembly was physically guarded by 1,000 mercenary Scythian archers, retained at state expense for the purpose of policing.[30] Many of the old factions and plutocratic elites, nevertheless, remained or subsequently reconstituted themselves.[31]

Views of the Acropolis from social media, 2021, the Acropolis viewed from the Pnyx in 1976, & Ruins of the Parthenon in 2014

Such was the situation at the time of the Persian Wars. The prestige of the victorious Athenian generals and statesmen from that period, notably, Miltiades (of the Philaidae clan, and victor of Marathon), Aristides (who organized the Delian League),[32] Themistocles (victor of Salamis), and Cimon (son of Miltiades), was so immense that they entirely dominated state policy. Miltiades, however, after capturing Lemnos, was imprisoned upon returning to Athens as a result of his failure to persecute the conquest of Paros in 489.[33] The appointment of archons was then further reformed in 488/7, into offices appointed by lot,[34] and, to curtail the influence of the general-statesmen, the institution of ostracism was invoked, whereby the Assembly could expel any citizen whose power was believed to be approaching that of the old tyrants.[35] Xanthippus, Pericles’ father, an opponent of Miltiades, was ostracized in 484.[36] Themistocles, meanwhile, was engaged strengthening Athen’s maritime connections, by fortifying the Piraeus and planning for the long walls that were eventually built in the middle of the century, but also alienating the Athenians by his pompous comportment, and was in turn ostracized in 472/1.[37] Aristides arranged the Athenian system of finance, by which 20,000 public servants were retained on state pay (see below).[38] Cimon, after numerous campaigns expanding the Athenian empire, was ostracized in 461, on the eve of the First Peloponnesian War, as we have seen.[39]

The long walls, and Piraeus, Map of Athens.

Just before the outbreak of the First Peloponnesian War (c.460/1), Athenian politics, and, in particular, its finances, was controlled by a faction of 300 elites. This centuries old Council of the Areopagus (the Hill of Ares, on the Acropolis),[40] was composed exclusively of former archons from amongst the nine archon offices: the basileus, or chief archon, responsible for sacrifices and religious rights;[41] the polemarchos who was commander-in-chief of the army,[42] high-magistrate for contract law,[43] and chief judge of the foreigners, metics – the citizens and non-citizens alike who were required to finance the public’s services (leitourgiai); the king archon, who presided over festivals; the eponymous archon, whose name became that of the year, and was responsible for family law; and the six thesmothetai who presided over trials.[44]

The Dipylon Gates, Inner Kerameikos, and straight road to the Academy

In 462/1 the populist Ephialtes was able to mobilize the Assembly to restrict the power of the Areopagus, but was later assassinated for his trouble.[45] Pericles, from the patrician, but thoroughly democratic, clan of the Alcmaeonidae – from which Cleisthenes was also a descendant,[46] and thus an opponent of the Laconian sympathizer Cimon, a Philaidaen – succeeded Ephialtes as the champion of Athen’s democratic faction. By taking advantage of the crisis resulting from the First Peloponnesian War, Pericles succeeded at reforming the judiciary and in opening the archons to a broader electorate.[47] But, in 451, he also restricted the citizenry to those whose parents were both Athenians.[48] Cimon, backing the power of the Areopagus, strove to frustrate then thirty-year old Pericles.

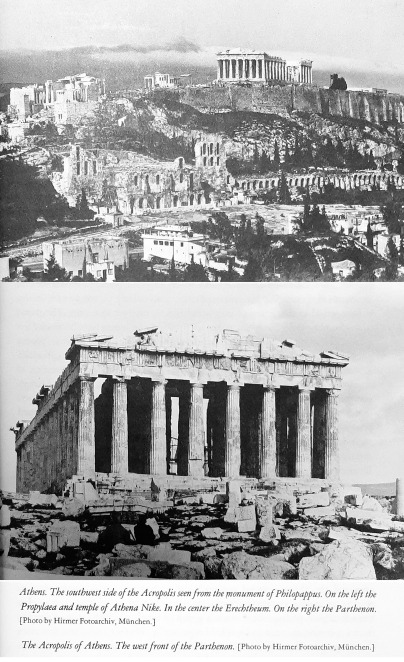

Views of the Acropolis. and Parthenon, from Raphael Sealey, A History of the Greek City States, ca. 700-338 B.C. (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1976)

As it happened, Pericles succeeded in breaking the power of the Areopagus, and as a result their former control over Athen’s finances devolved to the Council of Five Hundred, the boule, which had originally been established by Cleisthenes as a sort of rotating bureaucracy for the Assembly.[49] Composed of 50 citizens from each of ten reformed tribes, based on the Athenian districts (demes), the councillors were chosen by lottery as rendered by the kleroterion, a machine designed to select or discard groups of tribal candidates.[50] Citizens over the age of thirty were allegeable for annual service, but could only hold office in the Council twice during their lifetime, and act as epistates (chair of the prytaneis for 24 hours) but once.[51] Councillors (bouleutes), selected by the lottery, were required to undergo background examinations (dokimasia) by the presiding Council, prior to being sworn in, at which point they could join the Council meetings which were held, during the 5th century, in the Bouleuterion at the Agora.[52]

The Athenian Ecclesia, citizen’s assembly, at the Pnyx

The Council (boule), in turn, was administered by an executive, the prytaneis, of 50 councillors formed from each of the tribal groups, who were always in session and whose terms lasted thirty-five days (ie, 1/10 of the year).[53] Thus, each tribal group acted in the capacity as Assembly presidents for a little over a month. Councillors were paid by the state at the rate of five obols a day, and six obols (one drachm) for a prytaneis.[54]

The Bouleuterion in the Agora, meeting place of the Council of the Five Hundred. The prytaneion, state accommodations for prytaneis was nearby.

The prytaneis was responsible for preparing the Assembly’s agenda (probouleuma), which was done several days in advance of the Assembly’s weekly meetings, so that legislative matters could be voted on (cheirotonia) expeditiously. The prytaneis were also responsible for convening meetings of the full Council when required, and for entertaining foreign dignitaries at the Prytaneum.[55]

The kleroterion lottery, by which means candidates, representing the deme-tribes, were divided into rows of ten, and selected at random for the council and public services.

All magistrates, except the ten strategoi, were selected by the drawing of lots.[56] Athens was thus administered by a galaxy of magistrate colleges, usually numbering ten to reflect the tribal-demes (the latter overseen by demarchs): the ten astynomoi (controllers of the police and public works), the ten agoranomoi (supervisors of the agora who guaranteed exchange values and oversaw retailers), the ten metronomoi (inspectors of weights and measures), the ten epimeletai (port overseers who imported grain, maintained order at the docks, and oversaw wholesale merchants – and were responsible for issuing triremes to the Athenian trierarchs),[57] the nautodikai (magistrates of the Piraeus court),[58] the pentekostologoi (who levied the docking and transhipping fees),[59] the sitonai (civic grain buyers),[60] the sitopolai (grain sellers and their treasurer),[61] the hodopoioi (road surveyors with their slave labour pool), the chief architect, the poletai (public contractors), the praktores (tax collectors), the apodektai (receivers), the episkopoi (tribute collectors),[62] the kolakretai (treasurers of Athens), the Hellenotamiai (treasurers of the empire),[63] and their secretaries (xyngrammateus).[64] In addition, the courts were managed by the heliaia, citizens appointed as judges. Religious festivals, as mentioned above, were controlled by the nine residual archons (plus their secretary).[65]

Stadium at Delphi, 4th century, from Spivey & Squire, Panorama of the Classical World (2004)

Aristotle (384-322), whose Politics (written between 328-325) was informed by the research provided by his school for the Constitution of Athens, stated that the Athenian economy maintained about 20,000 persons at public expense: 6,000 members of the courts, 1,400 magistrates (700 domestic, 700 aboard), 500 members of the Council, 2,500 infantry, 2,000 sailors for 20 guardships, another 2,000 sailors employed to collect the League’s tribute, plus 1,600 archers, 1,200 cavalry, the 1,000 Scythian guards, 500 guards for the Piraeus, and another 50 for the Acropolis.[66]

Life in classical Athens

Thousands of slaves and servants were kept on state play including: councillors, clerks, sacred officials, amourers, shipwrights, secretaries, some doctors, temple attendants, dockworkers, mercenaries, miners, street sweepers, minters, the Scythian police, even the torturers and executioners employed by the dreaded Eleven, jailors,[67] and innumerable other lesser, or more essential, public functions; a myriad of public servants responsible for the city’s welfare. The important point here is to note the variety of services and the complexity of the system of state pay: although the majority of the population of Athens were slaves (perhaps as many as 150,000),[68] struggling in Athen’s various artisanal factories, workshops, and on farms and vineyards, it is significant that the fleet’s triremes were crewed by wage-earning rowers,[69] and that hoplites, and their servants, were maintained at the state’s expense while on campaign (even slaves had to be paid since they purchased their own food).[70]

Warfare in classical Greece

Warfare in classical Greece

The army was commanded by the strategoi, generals such as Cimon, Pericles, Cleon, Demosthenes, Nicias, and Alcibiades, who were elected directly by the Assembly, with no term limits, from amongst the ten tribes and thus hopefully representing all the demes in Attica.[71] In practice, following the Persian Wars, the strongest strategos came to wield immense influence. However, the interests of these formidable marshals were tempered by the requirement to divulge their accounts at the conclusion of their commands (euthyna), and they could be recalled, or even ostracised for ten years, at will by the Assembly.[72] Echoing Thucydides, John Hale’s described Athens as “in fact less a democracy than a commonwealth governed by the richest citizens.”[73]

For his failure to take Amphipolis in 424, Thucydides the historian was exiled from Athens. He retired to his family estate in Thrace and wrote his History. He died about age 56 in 404 (or 60 in 400), leaving the narrative of the Great Peloponnesian War to be completed by Xenophon.

The Spartan polis, and the Peloponnesian League

Geographic map of the Peloponnesus

Sparta, through its gradual conquest of Laconia and Messenia, became the largest Hellenic polis during the archaic period,[74] but the Spartan government, in comparison to the Athenian, was a model of simplicity. The Spartans, based on the laws established by Lycurgus, had evolved into a barracks-state: the city was ruled by twin kings, really hereditary high-priests who commanded Sparta’s army,[75] one from the Eurypontid and one from the Agiad family lines, while foreign policy and finance was administered by the five annually elected ephors,[76] a kind of central committee, who in turn summoned the popular gathering of the apella, and, likewise, acted as the executives of the gerousia, or senate, of 28 elders (over the age of 60), in consultation with the two kings.[77] The ephors were responsible for acting as a supreme court, and were tasked with enforcing morality amongst the Spartans. Two of their number also accompanied a Spartan king during campaigns.[78]

Enter Phormio, the Rebellion on Samos, 441

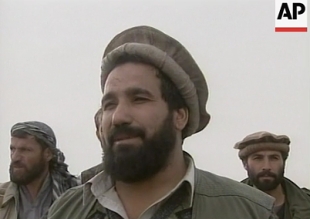

Phormio’s first appearance (chronologically) in Thucydides’ history, interestingly enough, is alongside the historian himself, Thucydides son of Olorus, who, together with Hagnon, another Periclean general, were leading a contingent of 40 ships to reinforce the Samos expedition of 440/439, which was then being executed by Pericles.[79]

2nd century Roman copy of a c. 430 bust of Pericles, c. 1786 drawing by Vincenzo Dolcibene, & anonymous drawing of the same, c. 1789-1817, British Museum, Towneley collection

Heavy-handed Athenian intervention by Pericles, in favour of democratic Miletus against oligarchic Samos in the dispute of 441,[80] caused the Samians to openly revolt the following year, being joined in this endeavour by the Byzantines, and envoys were sent to the Peloponnesus to ask the Spartans for aid. On this occasion the Corinthians intervened decisively, by refusing to support the Samos rebellion (citing the right of the league leader to coerce their allies – the same rationale the Corinthians would then employ in their attempt to dissuade the Athenians from intervening in the Epidamnus affair that brought the Corcyraean-Corinthian dispute of 433 to a head),[81] and, without Corinth’s support, Sparta could not coerce Athens.[82]

Ruins of the Heraion, Island of Samos, Sanctuary of Hera, and the Sacred Way running the 6 kms south from ancient Samos.

The Athenians were thus given a free hand in Samos. In 440 Pericles led the expedition with 60 warships and transports to suppress the revolt. 70 ships of the Samian fleet (including 20 transports) were scattered by Pericles’ 44 triremes off the island of Tragia, and the city of Samos was placed under siege. Pericles was distracted by perceived Phoenician intervention, and the Samians took the opportunity to run the Athenian blockade, but were only able to break through for a fortnight before Pericles returned with his fleet, now numbering 60 triremes. With the arrival of Phormio, Thucydides, and the others, Samos, after a siege lasting nine months, was starved out and forced to surrender, and shortly after this the Byzantines likewise submitted.[83]

Phormio’s First Intervention in Acarnania

Achaea & Aetolia

A few years later (Westlake, Busolt, and others, suggest 437, although Kagan and others,[84] believe the date is closer to, or even after, 433/2), after Phormio’s role in the defeat of the Samos rebellion and prior to his involvement in the Potidaean campaign (see below), the Amphilochians and the Acarnanians appealed to Athens to help them recover Amphilochian Argos from the Ambraciots, a Corinthian colony allied to several nearby tribes in western Hellas.[85] The Amphilochians were colonists originally from Argos, and the Acarnanians were a growing colonial polity, leaning in Athens favour, in the volatile frontier region of Aetolia, north of the Gulf of Corinth. The orchards of Aetolia, with its high mountains, and the animal wilds Epirus, were both important sources of pine, fir, and oak, essential commodities for ship-building, as well as the less dense, but more resilient, poplar or willow, material for the hoplite’s distinctive aspis shields.[86] Athenian access to Epirus, through Corcyra, was the draw that pulled Athens into the Epidamnian affair, ultimately leading to the naval showdown with the Corinthians at Sybota in 433, where the Athenians intervened decisively in Corcyra’s favour.[87]

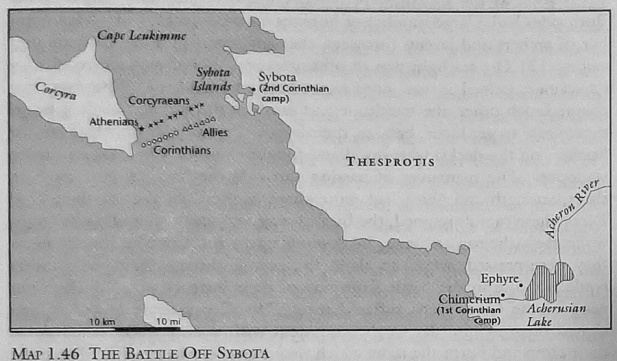

Battle of Sybota, 433, from The Landmark Thucydides

Pericles, responding to the Acarnanian request of 437, despatched Phormio with 30 ships. In a naval action near Naupactus, Phormio’s fleet of 30, deployed into five lines, defeated a grand Ambraciot fleet of 50, by forcing them to break up their formation during a chase, as recounted by Polyaenus.[88]

Phormio then deployed his army ashore and proceeded to make short work of the Ambraciots, enslaving their women and children, capturing Chalcis by stratagem, and recovering Amphilochian Argos. Phormio made off with a great deal of Chalcidian plunder.[89] The Acarnanians were so pleased with Phormio’s conquests that they formalized an alliance with Athens,[90] demonstrating the real political importance of the campaign – a component of Athen’s increasing influence in north western Greece and Italy: Kagan points to the treaties of Rhegium, Leontini, Phormio’s alliance, Diotimus’ expedition to Naples, and then the treaty with Corcyra of 433, as other examples.[91] When Phormio returned to Athens he was seasoned and wealthy, if not rich, still in his prime, with a reputation for guile, toughness, and hard training. He was also a family man with a son. Could there be greater triumphs still?

The Potidaean Campaign, 433/2

The forested highlands of north-east Hellas, Thessaly, Thrace and Macedonia, were important sources not only of timber and precious metals, but also alum, an essential ingredient in dye for Athenian textiles.[92] Potidaea, although originally a Corinthian colony, was at this time a member of the Delian League, and thus beholden to pay tribute to Athens.[93] A small polis (Delian League tribute assessed at 6 talents), but geographically significant port, Potidaea like Corinth, Byzantium, and, in later ages, Gibraltar or Singapore – one of the ‘the keys that lock up the world’ in Admiral Sir John Fisher’s phrase – was centred on a geostrategic bottleneck from whence tolls could be collected,[94] and much of the surrounding waterborne trade and maritime communications controlled.

The Chalcidice Peninsula, showing Potidaea and Pallene, where Phormio led siege operations in 432 BC.

The Potidaeans were known to be gravitating towards Corinth, perhaps because the Athenians were gradually increasing the tribute assessment on the Pallene peninsula and in neighbouring Bottice.[95] Kagan suggests the rationale for this tax increase had to do with the ongoing operations of the Athenians in Macedonia.[96] At any rate, over the winter of 433 the Athenians sent Potidaea an ultimatum, requiring them to dismantle some of their fortifications, provide hostages, and expel the Corinthian magistrates from their city.[97] The Potidaeans instead sent envoys to Corinth, who proceeded to inform the Spartans. Sparta guaranteed Potidaea’s independence, should the Athenians attempt to use military force to secure the tribute they were due that spring, thus establishing a showdown between the two blocs.[98]

The situation in Chalcidice was a significant one, as the Athenians had already deployed there an expedition of 30 ships, with 1,000 hoplites, commanded by five generals of whom the leader was Archestratus.[99] Kagan argues that Archestratus did not depart until April 432, at which time his mission had expanded to include the conquest of the Potidaeans.[100] Archestratus’ mission certainly involved the coercion of Perdiccas, the King of Macedonia, whose competitors for the Macedonian crown the Athenians in fact controlled.[101] Seeing an opportunity to aggravate the Athenians, Perdiccas encouraged the Chalcidians and Bottiaeans to join the Potidaean rebellion. This they did, establishing a regional federation with their capital at Olynthus, only seven miles away from Potidaea.[102] Perdiccas, meanwhile, despatched messengers to engage his diplomats at Sparta and enlist their aid against the Athenians.[103]

Potidea today, with canal & The seawall of Emperor Justinian

The Corinthians sent 1,600 hoplites to support the Potidaean federation, and presently the Athenians despatched Callias, in 40 ships with 2,000 hoplites, to reduce the region and return it to Athenian control.[104] Callias joined up with Archestratus, thus creating a combined expedition of 70 ships and 3,000 hoplites.[105] This total force must have numbered at almost 15,000 men (200 crew in each trireme, plus the 3,000 hoplites and their transports – whose true number would have been much higher when all the attendants, slaves and armourers were counted: see below). This expeditionary force was thus sufficient to isolate the Potidaeans from the Bottiaean side of the Chalcidice peninsula, although not yet enough to overcome them so long as they could access the Pallene.

The timing of these operations is worth noting: in the Aegean Sea the prevailing winds are north to south from May to September, but south to north from October to April,[106] and it is likely the Spartans held their war conference in August or November 432,[107] after the summer in which Pericles issued the Megarian Decree, restricting Megarian products from the Athenian market.[108]

Ruins of the theatre at Sparta, & the ancient agora

Phormio, known by his nickname melampygous for his tanned backside,[109] now enters the scene. He must have been nearing, if not over, 50 years of age in July 432, when he was granted command of reinforcements sent from Athens to persecute the amphibious expedition led by Callias who was then conducting the siege of Potidaea.[110] Diodorus says Phormio was sent to succeed Callias, thus assuming overall command of the operation, and stressing the close connection between Phormio and Pericles’ faction.[111]

Phormio’s orders were to deploy reinforcement to the Pallene isthmus, and thus completely isolate Potidaea. Phormio landed 1,600 hoplites on Pallene and established his base at Aphytis, setting out afterwards to attack Potidaea proper.[112] Demonstrating his experience at siege operations, Phormio had a wall built to cut off Potidaea, while the fleet blockaded the city from the Thermaic and Toronaic Gulfs.[113] The Corinthian commander in Potidaea, Aristeus, could see that defeat was only a matter of time, and so slipped out of Potidaea in a single ship hoping to continue operations from the mainland. The Corinthians and Megarians were soon attempting to induce the Spartans to declare war over the situation at Potidaea.[114]

Alliances and theatres of the Second Peloponnesian War

Phormio, with Potidaea surrounded but not yet secured, spent the rest of the campaign raiding the countryside, later capturing some towns belonging to the Chalcidians and Bottiaeans.[115] At this stage of the Chalcidian campaign (432/1) the Athenians were sustaining operations involving 4,600 hoplites and certainly more than 70 ships: a substantial amphibious expedition, although smaller than the Sicilian expedition of 415-413, which involved more than 200 triremes and over 10,000 soldiers (it is worth bearing in mind that Homer named 46 captains for the 1,186 ships of the Trojan expedition,[116] perhaps 83,000 men at a conservative 70 crew per ship, and that the hoplite force of 38,700 that defeated the Persians at Plataea in 479 must have required at least that number over again in helots and slaves to carry the armour and shields).[117] Each Athenian hoplite, when on campaign, was allowed two drachms per day to cover ration expenses for themselves and their servants.[118]

It is worth examining this question of manpower and finance in some detail, as the manpower allocation of the Athenian military provides some insight into Pericles’ maritime strategy, and indeed the future of Phormio’s career, as we shall see.

Athenian & Spartan Military Capacity

Colossal Zeus statue by Phidias, as it would have looked at the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, c. 435, from Nigel Spivey & Michael Squire, eds., Panorama of the Classical World (London: Thames & Hudson Ltd, 2004).

The Athenian deployment during the Potidaean campaign of 433 – 430, as we have seen, involved up to 4,600 hoplites and at least 70 triremes, with 70 triremes representing perhaps a quarter of the total Athenian trireme force capacity of 300.[119] There were also 1,200 cavalry (the knights, commanded by hipparchs) and 1,600 archers.[120] This force was supported by at least 13,000 sailors (at 170 rowers per trireme crew of 200, including marines, archers and officers), making for an expeditionary force of perhaps 18,000 men, not counting transports, armourers, slaves (the hypaspistai who carried the hoplites’ weapons, armour and supplies),[121] and other logistical elements. Transport ship cargo capacities ranged anywhere between 50 to 140 tons, a ship at the lower end being capable of carrying 400 amphora, ships at the higher end capable of carrying as many as 3,000-4,000.[122]

Zeus Ceraunaeus, from the Sanctuary of Zeus at Dodona, 470-460 BC

Assuming every hoplite had at least one servant (or slave), this brings the minimum manpower of the expedition to 22,200 – a formidable expense, approximately valued at 23,200 drachm per day (9,200 drachm at two drachm per day for each hoplite-servant pair, plus another 14,000 drachm per day to maintain 70 triremes). The expedition, therefore, must have cost nearly 116 talents, about 70,000 decadrachm, every month.

Full scale operations (and especially naval operations), however, only took place for about two-thirds of the year: the winter was usually spent conducting sieges. A reasonable estimate for the Potidaean campaign, therefore is about 560 talents for eight months of naval operations, and another 552 talents to support the land force for a year, or 1,112 talents all told.

Various drachma from the eastern mediterranean 600-300 BC, from the British Museum’s collection, and the Berlin State Museum. Towards the end of the 5th century, a gallon of olive oil cost about three drachm, a cloak of wool cost anywhere from five to twenty drachm, and a pair of shoes might cost between six to eight drachm, from Strassler, ed., The Landmark Thucydides, Appendix J (Thomas R. Martin), p. 622. Soldiers (and servants) were paid from three obols to one drachma a day to cover their expenses.

The Athenian empire’s mid-5th century punitive expeditions were indeed both intricate and expensive. A rough way to calculate the cost of a year of the war for Athens is to figure about 1,000 talents for the defence of the city, including all other other government expenses (about half of the total budget), plus at least another 1,000 talents for each significant maritime operation underway. Pericles, in fact, made it policy to set aside a reserve of 1,000 talents, and 100 triremes, to cover precisely such eventualities.[123] The siege of Samos, 441/0 had cost 1,400 talents of silver over nine months (155 talents per month, 93,000 decadrachm, comparable to the 116 talents or about 70,000 decadrachm that the Potidaean campaign must have cost every month). The total costs associated with building the Parthenon have been estimated at between 470 talents to as many as 1,200-1,300 talents,[124] indicating the relative cost of a years’ worth of an any punitive maritime expedition. The construction cost of a trireme was one talent of silver (6,000 drachm), while it cost another talent to pay a crew of 200 for one month.[125]

Athenian treasury at Delphi, built on the Sacred Way after the Battle of Marathon c. 490, to house Athenian offerings to the Pythian oracle. Not to be confused with the treasury of the Delian League, located first at Delos and then on the Acropolis. From Spivey & Squire, Panorama of the Classical World (2004)

Keeping 35 triremes in commission cost about 420 talents for a year,[126] comparable to the contributions of the Delian League in 454 BC (490-500 talents). Large operations, involving perhaps 150 triremes, and numerous other transports and communications craft, could therefore cost as much 1,700 talents for a year’s worth of operations, necessitating significant state borrowing, on top of which it was necessary to pay, or support, the thousands of slaves and servants owned or retained by the state.

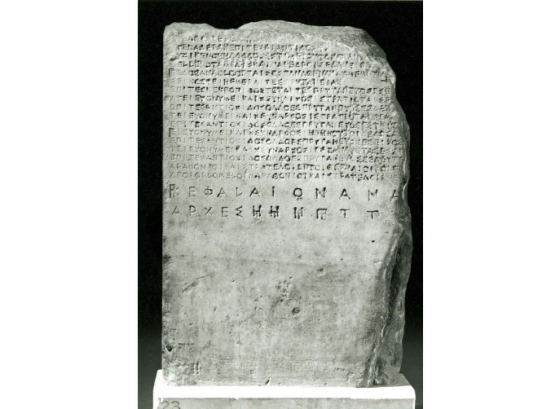

Fragment of Athenian Tribute List from 440/39, from Strassler, ed., The Landmark Thucydides, & marble block describing financial accounts issued by the Athenian Treasury, 415/4 BC, Lord Elgin collection. Chief Athenian allies and colonies included Chios, Lesbos, Corcyra, Plataea, Naupactus, the Zacythians, the Acarnanians, Rhegium, Leontini, and the Thessalians.[15]

In 431, Athenian state expenses accounted for perhaps 885-900 talents, to which must be added the cost of the Potidaean campaign, 1,112 talents, for very nearly 2,000 talents total expenses. In fact, the Athenians were spending even more than this at the outset of the war, as they borrowed 1,370 talents in 431 from their sacred treasuries,[127] suggesting the total state expenses for that year was perhaps 3,000 talents: 600 talents in tribute, 400 talents in state revenue (recycled back to the public through pay), another 1,100 for Potidaea, and then 1,370 talents borrowed from the sanctuaries.[128]

The trireme ship sheds at the Piraeus, and the modern Olympias in its shed, from Strassler, ed., The Landmark Xenophon (2009).

Under peacetime circumstances, during the second half of the 5th century BC, the Athenian empire generated approximately 1,000 talents per annum (about 600,000 decadrachm). In 431, approximately 400 talents were generated in Attica through exports (pottery, wood, wine, iron, bronze, wool and textiles, plus financial and legal services), and Attic taxes paid by non-citizens and foreign merchants, duties (ateleia), court fess, transport fees,[129] plus anchorage and docking fees (the pentekoste, or 1/50th).[130] The rest, 600 talents, came in the form of the imperial tribute,[131] ostensibly to maintain the navy – but the surplus, plus the revenue from the silver mining of the Laurium veins (worked by between 10,000 to as many as 20,000 slaves – at the higher end producing close to 1,000 talents per annum, to make up shortfalls),[132] was piled into the Athenian treasuries, at various sacred oracles.[133]

The Persian Empire

For comparative purposes, in terms of raw silver revenue, no Greek state could match the annual tribute of the Persian Empire: 14,560 Euboean talents at the time of Darius, according to Herodotus.[134] Egypt’s tribute alone accounted to 700 talents, nearly the revenue of the entire Delian League, in addition to producing 120,000 bushels of grain for the Persians, an invaluable resource that Athens attempted to annex on several occasions during the 5th century.[135]

Artifacts in the Piraeus museum

During the Thirty Years’ Peace the kingly sum of 9,700 talents (5.8 million decadrachm), had been amassed in the Athenian treasuries, of which 6,700 remained in the spring of 431 (3,000 talents had been spent improving the Acropolis and on the Potidaean campaign).[136] To finance military operations between 433 and 426, the Athenians borrowed 4,800 talents from their treasuries.[137] It can be seen, then, that the Athenians were carrying on the war at a loss, but had not yet exhausted their silver reserves after six years of incessant operations.

The 5th century BC Varna shipwreck from the Bulgarian Black Sea coast

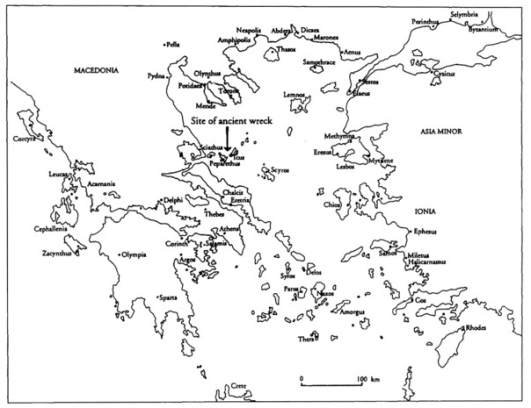

The late 5th century BC Alonissos shipwreck, carrying at least 4,000 amphora, primarily wine, most likely had a total cargo capacity of 140-150 tons.

Amphora detailed and recovered from the wreck, and location of Alonissos.

Example sizes of ancient shipwrecks, from From Alain Bresson, The Making of the Ancient Greek Economy (Princeton University Press, 2019), p. 87. The increasing size of bulk transports lowered the cost, with Athens exporting luxury and consumer goods en masse, outstripping the Corinthian trade.

The Athenian system of finance had evolved in tandem with the conduct and sustainment of these maritime operations, and – this is the key point – assuming operations were conducted biennially, or that there were sustained periods of peace or truces every six to eight years to allow the state coffers to refill, the war could in fact be sustained nearly indefinitely. On the other hand, the forthcoming loss of estate revenue to the Peloponnesian’s desolation of Attica would certainly strain Athenian finances, as would the ravishes of the plague during 430/29 and 427. What couldn’t be withdrawn from the state treasury would need to be borrowed, with interest, from the Attic religious sanctuaries, the hoards of treasure captured from the Persians and Peloponnesians, or even, in small quantities, from Athen’s domestic banking establishment (the latter estimated at 500 talents, plus another 40 in gold attached to the statue of Athena in the Parthenon).[138]

The Agora in the 5th century.

Ruins of Thissio, the Temple of Hephaistos overlooking the Agora

To summarize this rather arcane arithmetic: Athens could continue to function, and accumulate silver, while conducting minor seasonal expeditions, but would have to borrow annually from its limited reserves to finance the major operations required for the war against Sparta, Corinth, and Thebes. Nevertheless, so long as Athen’s artisanal exports and seaborne trade kept the League’s coffers filled with silver to pay troops and seamen, then the vital imports of staples and raw materials would continue to flow into the Piraeus, the location of the emporiom and a thriving urbanate in its own right. Charcoal from Delos,[139] timber from Euboea,[140] textiles manufactured in the Aegean, and fish and grain imported from producers around the Black Sea, in Sicily, Italy, and in Egypt, kept the city alive.[141] Athens was of course the largest single marketplace in the 5th century Mediterranean economy,[142] outstripping Syracuse, Carthage, Phaselis, and having already absorbed both Miletos on the Anatolian coast, and Samos in Ionia.

Attica and its environs, from The Histories by Herodotus, translated by Aubrey de Selincourt (London: Penguin Books, 2003 [1954])

Attica, Boeotia, Argolid, and the Corinthian Isthmus, showing Euboea, source of ship timber, and the silver mines at Laurium, from Rahe, Sparta’s Second Attic War (2020).

Indeed, as Peter Green has argued, the relative defensiveness of Pericles’ strategy, following the First Peloponnesian War, was the result of structural weaknesses in the Athenian economy, in particular, relating to the grain famine of 445 and the inability to secure grain supplies, first from Egypt (approximately 463-457),[143] and then under Cimon’s final command against Cyprus (451-450),[144] which meant importing from the Black Sea, Sicily and Italy at considerable expense.[145] Pericles’ democratic faction was constantly seeking alliances in Italy and Sicily from where grain could be imported,[146] and Pericles despatched colonists to Italy and Thrace to shore up Athen’s grain and timber supplies.[147] So long as the silver mines at Laurium remained active, however, the Athenians could continue to afford their seapower, and thus import grain to the polis.[148] These mines had paid for Themistocles’ fleet in 483/2, and, as Alcibiades recognized in 415, could be raided if the Spartans occupied the fortress at Decelea, thus interrupting the mining operations and stretching the Athenian economy to the breaking point.[149] In fact, everything hinged on the Laurium deposits, without which the intricate mechanisms of the Athenian empire would crumble one by one. The Spartans, until 413, ignored the critical fortress of Decelea for reasons relating back to the outstanding service of the Decelean Sophanes, who had fought heroically against the army of Mardonius at the battle of Plataea (479).[150]

Ruins of the Laurium silver mines, Attica

So much for the strategic implications of Athenian finance. In terms of manpower, the male adult citizen population of Athens proper has been estimated at between 30,000 and 40,000 during the 5th and 4th centuries,[151] with Xenophon (430-354), in the Memorabilia, counting some 10,000 houses in the city during his time.[152] The Theatre of Dionysus, after its expansion in the 4th century whence it became the seat of the Assembly, could seat 16,000 people.[153] Indeed, 18,000 or 20,000 men would have represented between 7% and 8% of Attica’s total pre-plague population of 250,000, of whom 150,000 were slaves,[154] and 20,000 foreigners (metics).[155] A lower estimate puts the total population at 150,000 – 170,000, in which case an expeditionary force of 18,000 represented 10.6% of the population, while a higher estimate puts Attica at 315,000 (5.7%).[156] It can be seen, therefore, that mounting expeditionary operations was a complicated and expensive logistical and military undertaking. Athens’ total hoplite capacity was 12,000-13,000, that is, citizens between the age of 18 and 60 trained and ready for deployment; although a further 16,000-17,000 men could be mobilized on short notice to defend the cities’ fortifications during the summer month when the Peloponnesians were actually raiding Attica.[157]

Theatre of Dionysus as it would have appeared in the 5th century, from The Greek Plays, eds. Mary Lefkowitz & James Romm (New York: Modern Library, 2017)

In short, during wartime, especially when the Athenians were outfitting triremes and conducting expeditionary operations, or when the Peloponnesians were attacking Attica, nearly the entire male citizenry (and a considerable number of metics, slaves and servants) were mobilized for war. The Peloponnesian army, in contrast, was vast; when fully mobilized numbering anywhere from 90,000 to 100,000 men, although it was never deployed as such all at once.

Young Spartans exercising, by Degas, illustration for Plutarch’s Life of Lycurgus, c. 1860

If they were outnumbered on land, however, in their political-economic system of finance and seapower, the Athenians were far in advance of the Spartans: the Peloponnesian League, indeed, had no system of finance to speak of.[158] Lycurgus had created 39,000 fields to organize archaic Sparta,[159] but, as a result of the lengthy training process for Spartan hoplites, Sparta’s frontline military capacity was strictly limited. The elite spartiates, warriors between the age of 20 and 45, numbered 8,000 in 480,[160] but their numbers had fallen, especially after the great earthquake of 464, and by 418 there were no more than 2,500 remaining.[161] The Spartans also had their helots, like the Cretan Perioeci, serfs, who farmed for the Spartans and accompanied them on campaign as armour carriers. There were between five and ten helots for every Spartan citizen, making the risk of helot rebellion a constant concern for Spartan strategy.[162]

The Delian League in 445, from Paul Rahe, Sparta’s Second Attic War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), & Map of Greece showing the Peloponnesian League and the Delian League.

The Peloponnesian League, from Paul Rahe, Sparta’s Second Attic War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020) & The Landmark Thucydides

As the war progressed, and Sparta’s casualties increased, it became policy to liberate helots willing to serve as soldiers – the neodamodeis. The numbers in this middle-class increased significantly during the course of the war, and by the beginning of the 4th century, as Aristotle observed, the Spartan polis could mobilize as many as 30,000 hoplites and 1,500 cavalry.[163] In this sense, it can be seen that Spartan society was ultimately transformed into a kind of feudalism during the course of the 5th century. In terms of seapower, of course, the Athenians were unmatched: in 431 the Peloponnesian League possessed no more than 100 triremes, mainly Corinthian. The Spartans presently circulated orders for their fleet strength to be built up to 500 through contributions in kind or in credit from their allies, although this construction program would require many years, and longer still to acquire the requisite skill to match the Athenians.[164]

Athens, Corinth, Thebes and Sparta

Ruins of Ancient Corinth, the Lechaion road

As Francis Cornford has observed, the Second Peloponnesian War was less an inevitable struggle between two power blocs than, “a struggle between the business interests of Corinth and Athens” for control of commerce and oceanic trade in western and northern Greece.[165] Corinth’s relative maritime-economic power had been in decline vis-à-vis the expansion of Athen’s as a maritime power,[166] especially since the conclusion of the Persian Wars. During the Archaic period, when cargo ships were smaller and long voyages perilous, cargos were hauled across the Corinthian isthmus and thus between the port of Kenchreai, on the Saronic Gulf, and the port of Lechaion, on the Gulf of Corinth.[167]

The partially submerged ruins of the temple of Isis at the port of Kenchreai, on the Saronic Gulf, and the ruins of the Lechaion port on the Gulf of Corinth

This transport corridor was vital for Corinthian and Megarian production.[168] The tracked diolkos crossing, capable of moving both cargo vessels and warships, had been built at the beginning of the 6th century by the Corinthian tyrant Periander.[169] Corinth, as Raphael Sealey observed, “was well placed for control of communications, and during much of the Archaic period pottery made in Corinth was exported more widely than that of any other Greek city.”[170]

The Corinthian diolkos, cargo and warship track crossing of the Corinthian isthmus & CGI depiction of an empty cargo vessel being hauled along the tracks.

By the 5th century, however, Athenian maritime trade around the Peloponnesus began to eclipse the transport value of the diolkos crossing, particularly in terms of grain and amphora exports.[171] Corinth, known for its high quality wool products, was being directly challenged by Athenian wool and textile production: the Athenians operated a quasi-industrial system, utilizing the Delian league itself as processing capacity for enormous quantities of textiles,[172] and as the source of strategic materials including everything from wool, timber, charcoal, dyes, to the ochre from Keos used for painting the triremes.[173] Foreigners (metics), in Athens, were thus highly regarded for their philosophical, architectural, industrial, mercantile, and financial, banking (trapezitai) prowess: Cephalus of Syracuse, the host of Plato’s Republic, was an arms manufacturer in possession of 120 slaves; the largest fish salting business in Athens was owned by the metic Chaerephilus; Hippodamus of Miletus was the architect of the Piraeus, and Miletus was likewise the polis of origin of Pericles mistress, Aspasia.[174] Furthermore, Athens was gradually cornering the market for slaves: the primary slave trade ran through Delos, Chios, Samos, Byzantium and Cyprus, with two in Attica itself, at Sunium – to supply the Laurium mines – and the other in the Athenian Agora (individual slaves sold for between two and six minas, that is, 200-600 drachm – Nicias, the famous general, owned 1,000 slaves, while someone of more bourgeoisie status might own 50).[175]

Photos of the Kyrenia ship reconstruction, a 4th century BC merchant ship capable of carrying about 50 tons (400 amphora) and the original wreck in its museum on Cyprus

Kagan describes a historiography that is critical of Pericles’ maritime strategy, considered too defensive given the considerable cost of the war, as outlined above.[176] Pericles was without doubt a defensive-minded leader, a careful strategist rather than thrusting commander, such as Cimon had been, but he was hardly implementing anything new. Rather, Pericles’ strategy was founded on the traditional Athenian maritime principles fostered by Themistocles. Furthermore, at the outbreak of the war, it was not yet clear what the Spartans would do, nor had the shape of the conflict emerged – the Theban advance against Plataea being a case in point. Pericles, who had fought against the Spartans at Tanagra (457) during the First Peloponnesian War, understood that Athens could not directly confront the Spartans, and thus had no intention of giving them the opportunity they desired to fight a pitched land battle on their terms.

The Thebes-Megera-Corinth corridor.

Indeed, despite Athens’ rising industrial, financial, and maritime power, so long as Corinth supported Sparta, and Thebes honoured the Peloponnesian alliance, the League possessed enough military power to challenge the Athenians, if not topple them. Corinth’s opposition to Athenian expansion, in particular, was guaranteed, given Pericles’ colonial expansion into Aetolia and Epirus in the north west, Chalcidice in the north east, and his effort to crush Corinth’s partner on the isthmus, Megara.

The Epidamnus and Corcyra incidents, 433 & the Megarian decree, 432

The Archaeological Museum on Corfu/Corcyra

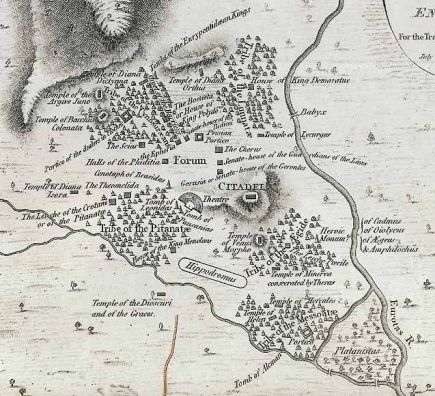

Flashpoints at the opening of the Peloponnesian War, locations of Epirus and Corcrya.

Pericles was content to employ Athen’s significant military-economic influence to gradually strangle the Peloponnesian allies, first, by supporting Corcrya against Corinth during the Epidamnus affair, and then by restricting trade with Megara (excluding them from the markets and harbours of the Athenian empire),[177] and, most directly, by deploying an expeditionary force to Potidaea.[178] It can been seen then that geopolitical relations between the Peloponnesians and the Delians were declining decisively during the period 433-431. Athens had reached the limit of its expansion in the Aegean and Ionia, the only remaining areas of expansion being in the west, in Sicily, Italy, Gaul and Spain, or to the north, in Thessaly, Thrace and Macedonia. It was over colonial influence in these distant, resource rich, regions that Athenian expansion collided with Corinthian and Theban interests, and it was these polis that were ultimately responsible for engaging the Lacedemonians against Athens.

Partial gold wreath, crown for Macedonian king, late 4th century, possibly Philip II or III. Spivey & Squire, Panorama of the Classical World, 2004.

Indeed, the Athenians were still conducting operations against Perdiccas in Macedonia during 432/1, while the Potidaean campaign was underway. Perdiccas was presently brought onside through Athenian diplomacy, and then joined forces with Phormio.[179] These operations, as we have seen, were already absorbing at least a third of the total Athenian fleet, and another 100 triremes were soon activated for operations around the Peloponnese.[180]

Greco-Roman bust of Socrates, who fought together with Alcibiades under Phormio’s command during the Potidaean siege, c. 432/1

The expeditionary commanders themselves were often personally responsible for keeping logistics flowing, including paying out of their own funds, an exigency that veritably bankrupted Phormio during the Potidaean campaign.[181] Indeed, from the Symposium we learn of the great difficulty of the siege: Plato has Alcibiades vividly describe the biting cold over the winter of 432/1, and the privations caused by the logistical shortages that reduced morale, so effecting Alcibiades, but apparently not the transcendent Socrates son of Sophroniscus.[182] Westlake is critical of this phase of Phormio’s career, noting that he was recalled and superseded by former co-commander Hagnon, with whom Phormio had been involved suppressing the Samos rebellion in 441. Hagnon, however, had only to finalize the siege and conduct mopping up operations, and it still required until 430/29 before the city fell.[183] Phormio, for his part, had broken the bank provisioning the Potidaea siege, and with Pericles’ faction temporarily out of power (see below), he could not expect sympathy from the Council’s review (euthyna) of his role in the campaign.[184]

Thebes launched an assault on the small but historically significant polis of Plataea in March 431

When the affairs at Corcyra, Potidaea, and Megara were collectively raised with the Spartan assembly, late in 433/2,[185] the conclusion of the majority was that the Athenians, by their actions, had broken the Thirty Years’ Peace (after only 14 years), and so the Spartans prepared for war.[186] In the event, the Theban attack on Plataea in March 431 forced the issue, with Thebe’s ineptitude necessitating Spartan intervention.[187]

Key Athenian fortresses on the Attic borders of Megara and Boeotia

In the summer of 431, therefore, Spartan King Archidamus led two-thirds of the Peloponnesian army, perhaps 60,000 men all told – hoplites, light troops, cavalry, and servants – into Attica (the other third was kept in Laconia to counter Athenian coastal raids).[188] Archidamus proceeded to besiege the Attic-Boeotia frontier fort of Oenoe, one link in a chain of forts that protected the borders of Attica.[189]

Sanctuary of Asclpeius at Epidaurus. Epidaurus was raided in 430 by an amphibious expedition led by Pericles.

While the Peloponnesians were laying siege to Oenoe, Pericles’ faction (Phormio, Hagnon, Socrates son of Antigenes, Proteas son of Epicles, Callias, Xenophon son of Euripedes, Cleopompus, Carcinus, Eucrates, and Theopompus),[190] put into place their expected maritime strategy. Carcinus, Proteas, and Socrates set out with 100 ships (plus 50 triremes from Corcyra and handfuls from other members of the League),[191] carrying 1,000 hoplites and 400 archers, to raid Laconia, Elis, and the Corinthians in Acarnania, where they captured Sollium and Cephallenia.[192] This opening raid was a dry-run for the larger expedition Pericles personally led to Epidaurus the following year. Simultaneously, a fleet of 30 triremes under Theopompus was despatched to Opuntian Locris, from which the Peloponnesians could potentially interdict Athenian trade with Euboea. Theopompus captured Thronium and defeated a Locrian army at Alope.[193]

Theopompus, with 30 triremes, raided eastern Locris (highlighted in yellow) in the summer of 431

Having failed to capture Oenoe, Archidamus circumvented the fort and marched into Attica to ravage Acharnae (a particularly wealthy Athenian deme), but after about a month the Lacedaemonians exhausted their supplies and departed via Boeotia.[194] In response, the Athenians first expelled the Aeginetans from the island of Aegina,[195] and then Pericles marched 10,000 men, plus 3,000 metics and a number of light troops, into the Megarid and raided the land, a deployment the Athenians repeated twice ever year (once during the summer after the Spartans had departed, and once again in the fall when the grain was being planted),[196] until 424 when they captured the Megarian port of Nisaea on the Saronic Gulf.[197] The fleet of 100 Athenian triremes, lately abroad raiding the Peloponnesus and the Corinthian possessions in Acarnania, had just reached Aegina and thence sailed to the isthmus to support Pericles.[198]

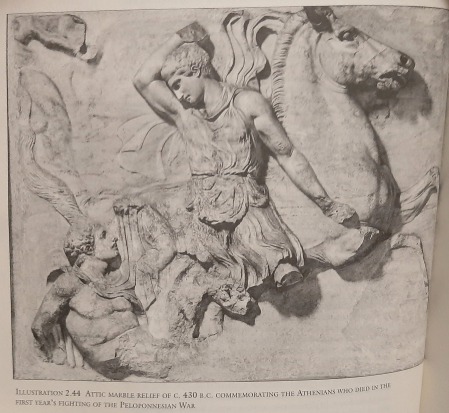

The following year, 430, Archidamus again raided Attica, spending 40 days there while Pericles personally led the fleet to raid Epidaurus.[199] The plague, meanwhile, began to spread in Athens, by 427 ultimately killing 4,400 hoplites and 300 knights, not to mention perhaps one third of the city’s population.[200]

Pericles delivering the funeral oration from the Pynx (actually delivered at the public sepulchre outside the city walls, see Thuc. 2.34) at the conclusion of the first year of the war, 432/1, by Philipp Foltz (1852)

The Acarnanian Campaign, 429

Upon return to Athens from Potidaea in 431/0, Phormio found himself in trouble with the authorities for his conduct of the campaign: his supporters in Pericles’ faction were out of power; Pericles had been censured and fined in 430 and was out of office until the following spring (peace envoys were despatched to Sparta, but rebuffed),[201] and, as a result of his euthyna (debriefing), Phormio was fined or charged 100 sliver minas to settle his accounts.[202]

This narrative is based on the fragmentary history of Androtion, which Hale places in 430 – although Westlake, citing also Pausanias, places it after Phormio’s return from the Acarnanian campaign in 428, a reconstruction that was also favoured by Felix Jacoby.[203] Phillip Harding, however, strongly rejects this thesis.[204] The 100 minas fine was not substantial, but was symbolic for the distress the Athenian Assembly felt concerning the length and cost of the Potidaean campaign. When the generals Xenophon, Hestiodorus and Phanomachus returned from Potidaea, after concluding the siege during the winter of 430/29, they were likewise charged but acquitted (Thucydides says only that “the Athenians found fault with the generals for agreeing terms without their authority, as they thought they could have achieved the unconditional surrender of the city”).[205]

The modern cemetery at Paiania

Phormio, as the story goes, refused to pay his fine, and was deprived of his citizenship (atimia) and thus banned from the consecrated sites in Athens, including the Acropolis, Pnyx, and Agora. Phormio, thus sanctioned, impoverished, and closing in on 50 years of age, departed Athens to return to his ancestral estate in Paiania, east of Mount Hymettus.[206] Paiania had been raided by the Peloponnesian chevauchee that year, but Phormio was no stranger to adversity, and, importantly, he was outside Athens when the plague struck (and, in the event, the Peloponnesians did not raid Attica in 429 – as Archidamus was engaged against Plataea).[207]

Nevertheless, as the summer of 430 ended, a group of Acarnanians sought out Phormio in an attempt to enlist him once again in their defence.[208] The Athenian assembly, still led by the “war party” headed by Cleon,[209] recalled Phormio and, on condition that he “decorate the sanctuary of Dionysus”, canceled his debt of 100 minas.[210] This is the source of the poetic verse, “Phormio said, ‘I’ll raise three silver tripods!’ / Instead he raised just one – made out of lead.”[211] Phormio’s appointment was to command of the crucial Acarnanian region, an area he was familiar with, having suppressed the Ambraciots there some years before when he solidified the Acarnanian-Athenian alliance, as we have seen.[212]

The Acarnanian theatre of operations & details of the Crisaean Gulf, from The Landmark Xenophon, ed. Robert Strassler (2009)

Phormio was given 20 ships – the only crews that could be assembled, considering the sickness inflicted by the plague – whereas the Athenians had deployed more than 130 ships in 431.[213] Hale states that Phormio’s flagship was none other than the Paralus itself, one of the two state triremes (the other being the Salaminia), however, his citation to Polyaenus does not in fact identify the name of Phormio’s ship.[214] At any rate, Phormio, during the winter of 430/429, rounded the Cape of Rhium, and arrived without incident at the small harbour of Naupactus, a colony settled in part by liberated Messenian helots, who had been freed by the Athenians as a result of the helot rebellion of 464.[215] His mission was to intercept shipping, and prevent the Peloponnesians from making use of the Corinthian Gulf to move supplies and forces from Achaea to Aetolia.[216]

Modern marina at the harbour of Naupactus (Nafpaktos)

Not long after Phormio departed for his command, Pericles’s faction, about the spring of 429,[217] was restored to power – although Pericles, due to his bout with the plague, did not have long to live.[218]

The Spartans, meanwhile, focused their efforts during the 429 campaign season against Plataea, which the Thebans had thus far been unable to reduce.[219] The garrison of 400 Plataeans and 80 Athenians hoplites, plus 110 female servants, held out under the Peloponnesian siege – including an attempt to torch the city which was narrowly defeated by a timely thunderstorm.[220]

The Athenians simultaneously continued their operations on the Chalcidice peninsula. Xenophon, son of Euripides (neither the famous Socratic general-historian nor the tragic playwright), and Phanomachus, so recently acquitted by the Athenians now that Pericles was back in power, were sent back to Chalcidice with 2,000 hoplites and 200 cavalry.[221] Their mission was to build on the capture of Potidaea by suppressing the rebellious Thracians, starting with Bottian Spartolus.[222] This expedition, however, came to disaster, as the Olynthians reinforced Spartolus and forced a battle, in which their light troops and horse outmaneuvered the heavy Athenians hoplites and inflicted 430 fatalities. Both Xenophon and Phanomachus were killed.[223] The survivors fled to Potidaea and thence back to Athens.[224] The war was now shifting to the west, where Phormio was stationed at Naupactus in Aetolia.

The Megarians had steadily been expanding their trading influence in Aetolia,[225] and in the summer of 429 Acarnanian, a Delian League ally of Athens because of Phormio’s intervention after 440, was once again threatened by their rivals, the Corinthian-Ambraciots and the ‘barbarian’ Chaonians. For the Ambraciots and their allies the time was indeed opportune, as the Athenians were distracted elsewhere by the Theban-Spartan siege of Plataea, the disastrous operations in Thessaly, and the deprivations of the plague.

The Ambraciots, therefore, mobilized to invade Acarnania, and despatched diplomats to the Peloponnesian League to gain their support. The Spartans agreed, thoroughly supported by the Corinthians,[226] and arranged to send a fleet, and 1,000 hoplites, to conduct amphibious operations against Acarnania.[227]

The Acarnanian theatre of operations

The plan of campaign was to assemble their allies at the island of Leucas and then reduce the coastal Acarnanian settlements, capturing the Athenian colonies on the islands of Zacynthus and Cephallenia, and possibly even Naupactus itself. Success in all of these operations would have seriously damaged the Athenian maritime network, potentially cutting off contact with Athen’s vital Sicilian colonies and Illyrian allies.

The Spartan amphibious component was commanded by Cnemus, an aggressive but temperamental commander, who had conducted a raid against Zacynthus with a force of 1,000 hoplites the previous summer (430).[228] Cnemus was sent ahead with a small detachment, transporting his hoplite force, with orders to take command of the Leucadian, Anactorian and Ambracian ships, while the rest of the expedition assembled, including triremes from Corinth, Sicyon and others.[229] Cnemus’ vanguard eluded Phormio, who was presently observing the Corinthian preparations from his base at Naupactus.[230] The Peloponnesian fleet gathered at the island of Leucas, and Cnemus went over to the Aetolian mainland to mobilize his various Greek and tribal contingents.[231]

In Acarnania, Cnemus’ thousand Spartan hoplites were bolstered by the arrival of troops from Ambracia, Leucadia, Anactoria, 1,000 Chaonians under Photys and Nicanor, some Thesprotians, Molossians and Atintanians under Sabylinthus, Parauaseans under their King Oroedus, 1,000 Orestians, subjects of Antiochus, and 1,000 Macedonians who were marching to join them, the last an interesting development considering that Perdiccas (who had switched sides again) was simultaneously fighting the Athenians on the Chalcidice peninsula, as we have seen.[232] Cnemus thus had under his command a sizeable force, but mainly irregular tribal auxiliaries around a core of Spartan, Leucadian, and Ambracian hoplites. He divided the army into three columns.[233]

Ancient theatre, and acropolis, at Stratus (Stratos)

Cnemus, believing he now possessed an overwhelming force, and, without waiting for the Macedonian or Corinthians reinforcements, started his march. The expedition quickly captured Amphilochian Argos, sacked the village of Limnaea, and advanced on Stratus, the Acarnanian capital.[234] The approach on Stratus was frustrated when the column led by the Chaonians rushed ahead of the main force, and were ambushed by the city’s defenders, including slingers. The Chaonians broke under this spoiling attack, falling back towards the Hellenic columns, where they continued to be harassed by the Acarnanian slingers.[235] Cnemus, having now encountered the first resistance, at once withdrew the entire army to the river Anapus, about nine miles from Stratus, and then to Oeniadae, which was the only polis in Acarnanian open to the Peloponnesians.[236] Here he disbanded his tribal contingents, and then withdrew with his 1,000 hoplites to Leucas. Westlake points out that this expedition accomplished little, but if this was only the vanguard of the Peloponnesian army, then Cnemus had done his job by testing the quality of the local combatants, thus preparing the way for the Corinthian and Macedonian armies to follow. But since his expected Corinthian reinforcements never arrived – having been intercepted by Phormio, as you shall see below – he then sailed back to the Peloponnesian port of Cyllene, in Elis.[237]

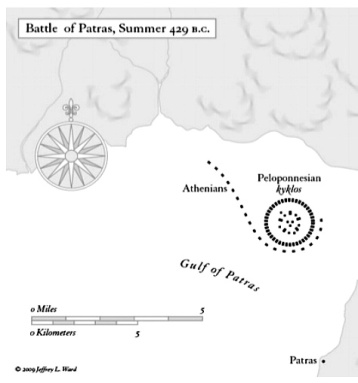

Before their victory over Cnemus, the Acarnanians had despatched heralds to alert Phormio at Naupactus. Phormio, observing developments at Corinth, replied that he could not leave Naupactus, given the imminent deployment of the Corinthian and Sicyonian fleets.[238] When this combined fleet of 47 ships (mostly transports, commanded by Machaon, Isocrates and Agatharchidas) set sail, Phormio shadowed them. The Corinthians sailed close to the Achaean shore, while Phormio prepared to intercept the convoy if it attempted to cross over to Acarnania.[239] After both fleets had crossed the narrows at Rhium, the Corinthians attempted to sail from their anchorage when it was still night, cross over to Oeniadae or Kryoneri,[240] and thus avoid Phormio, but were detected leaving their base at Patrae.[241] Early that morning, therefore, Phormio sortied from his station at the mouth of the river Evenus, and closed with the Corinthians crossing from the opposite shore, thus compelling them to battle.[242]

Battle at Patrae, Phormio surrounds and captures a dozen of the Corinthian transports, but the Corinthians escape to rendezvous with Cnemus, from John R. Hale, Lords of the Sea

To protect their convoy, the Corinthian triremes formed into the well known wheel (kyklos) formation, prows outward, surrounding their transports and five reserves triremes, much as the Athenians had done at Artemisium in 480.[243] Phormio, imitating the technique of the tuna fishermen,[244] formed his squadron into a line, and proceeded to row around the Corinthian formation, forcing them to close ranks, while he waited for the wind to come up and sow confusion amongst the Corinthians.[245]

This was indeed what took place, as Phormio had expected: when dawn broke, the eastern wind picked up, and the transports and triremes collided in the swells, at which point Phormio made the signal to attack.[246] He was rewarded by the immediate sinking of one the Corinthian command ships (Diodorus says this was in fact their flagship).[247] The Corinthians panicked, and Phormio swept up twelve of the enemy’s vessels, made prisoner their crews, perhaps 2,000 men or more,[248] the rest fleeing to Patras. Phormio rowed into Molycreium with his captures, where, at Rhium, the Athenians set up a trophy and dedicated one of the captured ships to Poseidon, before retiring back to Naupactus.

Excavated acropolis at Molycreium (Molykreio), a district of Antirrio, with the modern Rion-Antirion bridge across the narrows visible.

The surviving Corinthian ships withdrew from Patras to Dyme in Achaea, and from there to the Cyllene dockyard on the western coast of the Peloponnesus, in Elis.[249] Cnemus, himself withdrawing from his fleet base at Leucas following the defeat at Stratus, now sailed to join the Corinthians at Cyllene.[250] As Kagan puts it, “the first major Peloponnesian effort at an amphibious offensive had resulted in humiliating failure.”[251] Appalled at this series of reversals, the Spartans despatched Timocrates, Lycophron, and Brasidas, the last a rising star in the Spartan pantheon (a general and diplomat, Che Guevera-like figure for Thucydides),[252] to Cyllene to browbeat Cnemus,[253] and to recruit additional ships from amongst the Peloponnesian allies to reinforce the fleet.[254]

Ruins of Elis, theatre visible at lower left, capital city of the Eleans.

Phormio had not been idle. While he waited for the Peloponnesians to again take the sea, he despatched messengers back to Athens requesting reinforcements. The Athenians sent twenty ships, but with complicated orders that involved first deploying to Crete to assist with the reduction of Cydonia.[255]

Phormio, as such, was hard pressed. Cnemus had by now gathered 77 ships, drawn from Sparta, Corinth, Megara, Sicyon, Pellene, Elis, Leucas, and Ambracia, and was ready to force the crossing to Aetolia.[256] The Peloponnesian army had thus marched to Panormus to await transport across the narrows at Rhium, once the Athenian squadron had been reduced. Phormio, likewise, deployed again with his 20 ships to Molycreium, to keep watch on the combined Peloponnesian fleet.[257] Westlake and Rahe alike consider Phormio’s insistence on cruising in the Gulf of Patras a significant error, in that he left Naupactus open to attack.[258] However, it is also clear that Phormio’s mission was to prevent the Peloponnesians from crossing to Aetolia, and he could not achieve that aim hiding in harbour. With Phormio thus stationed outside the narrows, and the Peloponnesians stationed within, the two fleets waited.

Battle of the Rhium Strait/Naupactus

For about a week the two fleets stood off, training, and preparing for the action that was certain to follow. Cnemus and Brasidas at last determined to attack, before Athenian reinforcements could arrive.[259] The Peloponnesian commanders made a speech to their force, declaring that their greater numbers, both on land and at sea, combined with their certain valour, under more experienced commanders, gave them the advantage – however, the uncertainty of this proclamation was exposed by their threats against cowardice.[260]

Phormio, seeing the concern amongst his sailors given the great disparity of numbers, also delivered a speech, stating that the Peloponnesians would not have assembled so large a fleet if they were truly confident in victory, and that Sparta’s allies could not possibly hope to triumph except under Lacedaemonian compulsion. Phormio outlined his intention to force the Peloponnesians to fight in the open sea, and concluded with words rendered by Thucydides to the effect: “Be prompt in taking your instructions, for the enemy is near at hand and watching us. In the moment of action remember the value of silence and order, which are always important in war, especially at sea. Repel the enemy in a spirit worthy of your former exploits. There is much at stake; for you will either destroy the rising hope of the Peloponnesian navy, or bring home to Athens the fear of losing the sea. Once more I remind you that you have beaten most of the enemy’s fleet already; and, once defeated, men do not meet the same dangers with their old spirit.”[261]

Map showing the Gulf of Patras, narrows of Rhium, & Achaea and Elis

The Peloponnesians, however, had no intention of sailing into Phormio’s trap outside the narrows. Instead, they weighed anchor in the morning on the 6th or 7th day, and split the fleet into two divisions: the main force, in ranks four deep, sailed for the northern shore, while the right wing of 20 of the fastest ships, under Timocrates in a Leucadian trireme,[262] was to prevent Phormio from escaping should he retreat back inside the narrows to Naupactus.[263] Brasidas, and to a lesser extent Cnemus, have generally been credited with this plan.[264] Realizing that the Peloponnesians were preparing to make for Naupactus, and thus capture Phormio’s base, he deployed in single file, holding the middle of the line himself, and hugged the coastline back through the narrows, with his few hundred Messenian hoplites following along the shore.[265]

Battle of Rhium or Naupactus: Phormio is cut off by the combined Peloponnesian fleet, but then overcomes the over-confident Leucadians and crushes their main force, from John R. Hale, Lords of the Sea

Once Phormio was past the narrows, the Peloponnesians executed their plan, making full speed against the Athenian line, hoping to smash Phormio’s ships against the shore, while simultaneously cutting him off from his base.[266] Eleven of the Athenian ships, nevertheless, out-sailed Timocrates and the Peloponnesian right wing and escaped to Naupactus, but the remaining nine were caught and driven ashore.[267] The Athenian line had been cut, with Phormio’s trireme the last of the eleven to escape. Overwhelmed, crews of the nine trapped Athenian triremes swam for their lives – others were killed fighting. Thucydides, from this point on in the narrative, does not mention Phormio specifically,[268] however, other sources provide details that support his central role in what followed.