Operation Urgent Fury: Cold War Crisis in Grenada

Prelude

US President Ronald Reagan and First Lady Nancy at Andrew Air Force Base, 23 April 1983, honouring victims of the 18 April Beirut US embassy bombing.

On Friday, 21 October 1983, President Ronald Reagan was in a budget overview meeting. Afterwards, the President met with Henry Kissinger and the Commission on Central America. Communist infiltration into Nicaragua was discussed. Finishing up the week, the President departed the White House for the Eisenhower cottage at the Augusta Country Club in Atlanta. With Reagan went Secretary of State George Shultz and his wife, along with the newly appointed National Security Advisor Robert “Bud” McFarlane.[i] The President was expecting developments in the Lebanese crisis, bright on the National Security Council’s (NSC) radar after the US embassy bombing in Beirut that April

The President turned in for bed after dinner, but was awoken hastily at four in the morning. It was Bud McFarlane and George Shultz. The President had been requested to authorize the invasion of Grenada, led by the United States, and supported by the Dominican headed Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), formed in 1981 and composed of St. Lucia, Montserrat, St. Christopher-Nevis, Antigua, Barbuda, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and Grenada.

Secretary of State George Shultz being updated by satellite phone while staying at the Augusta Country Club, Atlanta Georgia, 21 October. From Edgar F. Raines, The Rucksack War (2010).

The US President spoke to Margaret Thatcher by phone on the 22nd and the British Prime Minister requested calm, emphasizing that no immediate military action should take place. For the British government, the twin crisis in Grenada and Lebanon came too soon on the heels of the 1982 Falkland’s war, itself involving a major amphibious operation requiring carriers and assault ships acting against an island base.

President Reagan at the Eisenhower cabin in Atlanta, Georgia, consulting with Secretary of State George Shultz and National Security Advisor Robert “Bud” McFarlane early on the morning of 22 October. & Teleconferencing with NSC staff, 22 October.

Discussion and a 9 am teleconference followed, after which the President approved Operation Urgent Fury – the invasion of Grenada – and then went back to sleep.Since the end of American military involvement in the Vietnam war in 1973 and the subsequent over-running of Saigon in 1975, there was a perception that the United States was reticent to utilize military action in a potential conflict. Jimmy Carter had put his presidency on the line over Operation Eagle Claw – the effort to rescue American Iranian embassy hostages in 1980 – and so the decision to intervene weighed heavily on the mind of his successor.

Reagan spent the rest of Saturday, October 22nd playing golf, a normally mundane event punctuated by the incident at the 16th hole: A gunman held up the golf shop, taking hostages and demanding to speak to the President. While he was being escorted away from the country club, Reagan called the gunman as requested, but the man on the phone hung up every time the President got through.[ii] The man was duly apprehended after his hostages escaped.[iii]

At 2 am the following morning, Sunday 23 October, Reagan was awoken again and informed about the Beirut barracks bombing and the enormous death toll, later reports finalizing at 242 Americans and 58 French dead.[iv] The suspects included the Iranians, Syrians, or the organization that eventually became Hezbollah.[v] The killing of so many American marines and French peacekeepers – one-fourth of the US component of the four nation peacekeeping force – came as a shock. This second major attack followed closely on the heels of other United States Marine Corps (USMC) casualties, resulting from sniper-fire and a car-bombing incident against a convoy on 19 October.[vi]

The President returning to Washington on 23 October.

The morning of Sunday, 23 October President Reagan, Shultz and MacFarlane returned to Washington D.C. Hurried meetings with the National Security Council followed, and it was decided to continue with the invasion of Grenada. Special Operations Forces (SOF) were going in immediately, flown 1,500 miles by C-130s to investigate landing beaches for the Tuesday morning attack.

Before finishing for the evening, the President briefed congressional leaders Tip O’Neill, Jim Wright, Bob Byrd, Howard Baker, and Bob Michel about the invasion, and then took a phone call from Margaret Thatcher, who, again, warned of the potentially negative international reaction to American military action and advised against rushing the operation.[vii]

In the Caribbean waters around the small Windward Island nation of Grenada, nevertheless, an amphibious assault ship and an aircraft carrier battle group – hundreds of thousands of tons of warships – laden with United States Marines, aircraft, helicopters, artillery and commandos, was assembling under the command of Vice Admiral Joseph Metcalf,[viii] and Major General H. Norman Schwarzkopf,[ix] to overwhelm Grenada’s small People’s Revolutionary Army (PRA), and its Cuban and Soviet bloc fighters. Combined Joint Task Force (CJTF) 120 was steaming steadily towards Grenada. Operation Urgent Fury was about to begin.

SR-71 Blackbird and TR-1 (U-2), high altitude reconnaissance aircraft of the type used by the CIA and Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) to photograph Grenada between 20 – 24 October 1983

CJTF 120, responsible for carrying out Operation Urgent Fury, led by Vice Admiral Metcalf, has itself become a model for joint operations. Meltcalf’s career and resolute decision-making during the thirty-nine hour planning phase prior to Operation Urgent Fury’s execution are now considered a military case-study in leadership during an international crisis.[xiii] Furthermore, the future commander of Central Command, Major General H. Norman Schwarzkopf, had been significantly influenced by his role as Metcalf’s deputy during Urgent Fury, and thus the otherwise brief campaign in Grenada is of interest to those studying the Gulf War and the end of the Cold War.

This post examines Urgent Fury and its planning, providing the reader with the essential battle-narrative and conclusions required to understand the nature of the conflict and judge why, in a House Appropriations Committee meeting on 26 February 1986, Secretary of the Army John Marsh and Chief of Staff of the Army General John Wickham testified that Urgent Fury had been a great success and, as General Wickham put it, “…a whale of a good job”.[xiv] Likewise, the seventh edition of the Marine Officer’s Guide describes Urgent Fury as a, “coup de main”. On the other hand, Norman Schwarzkopf would later write that, “the coup de main had failed utterly” and Sean Naylor, in his history of JSOC, described Urgent Fury as, “a fiasco”.[xv]

Maurice Bishop, Revolutionary Prime Minister of Grenada (1979 – 1983)

Ultimately a successful joint campaign, the brief struggle over the future of Grenada is a watershed moment in the history of the Caribbean during the Cold War.[x] The United States was set to reassert itself through a massive conventional arms buildup and a more aggressive foreign policy.[xi] Utilizing a combined force architecture that included Navy, Marines, Army Rangers, Airborne, and JSOC Special Operations Forces (SOF), components, the planning and execution of Operation Urgent Fury should not lightly be dismissed as a brief example of US imperialism or a distraction in some calculated Machiavellian dry-run for a futuristic cold-war doctrine.[xii]

Far from it, the Caribbean leaders outside of Cuba could see where the political situation in Grenada was heading. The US, with historical interest in the integrity of the Caribbean states, especially those members of the British Commonwealth, including Grenada, had a responsibility to protect the islands from internal conflict and their exploitation by the Soviet Union. The United States was requested to enable what the local Caribbean forces did not have the capacity to implement: the capture of the traitorous members of Bishop’s cabinet, and the People’s Revolutionary Army (PRA) junta who had overthrown the island’s government and murdered Maurice Bishop.

PART ONE

A Revolutionary Spark

Grenada in 1983 was a favourite tourist destination, only 133 square miles in size, with a population of 110,000. Grenada’s significant domestic product was nutmeg, of which the island produced a third of the world’s supply. Grenada had been a French colony until captured by Admiral Rodney’s forces in February 1762 and then ceded to Great Britain by the Treaty of Paris at the end of the Seven Years War.[xvi] Although briefly captured by France during the American Revolutionary War, the island remained a member of the British Commonwealth into the 20th century. In 1983 Grenada was home to more than 600 medical students at the island’s St. George’s University, comprising the majority of the 800 Americans and 120 other foreign nationals then visiting Grenada.

Daniel Ortega, Maurice Bishop and Fidel Castro.

In March 1979 Maurice Bishop’s New JEWEL (Joint Endeavour for Welfare, Education, and Liberation) movement, including Colonel Hudson Austin (chief of the Grenadian armed forces), seized power in a bloodless coup, overthrowing the corrupt Sir Eric Gairy. 1979 was a critical year in the Cold War. That year the Somoza family, led by Anastasio Somiza, was overthrown in Nicaragua, General Romero was ousted by a coup In El Salvador,[xvii] and Ayatollah Khomeini returned to head the revolutionary government in Iran.

Fidel Castro greeting Maurice Bishop; The Grenada Papers by Paul Seabury and Walter McDougall (1984).

In Havana, Castro’s Cuba quickly aligned with Bishop’s Marxist government, agreeing to finance the construction of a modern airport at Point Salines on the southern-most tip Grenada.[xviii] US analysts believed this airfield, scheduled for completed in January 1984,[xix] would enable the operation of MiG-23s from Grenada, while also acting as a staging ground for guerrilla deployments to Central America and West Africa.[xx]

Letters from the New JEWEL government to Yuri Andropov, then the Chairman of the State Security Committee of the Politburo, and the future General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, requesting counter-intelligence training. Also a letter to the Ministry of Defence of the USSR requesting military training. From The Grenada Papers by Paul Seabury and Walter McDougall (1984).

Bishop, despite his revolutionary Marxism, had recently shown signs of gravitating towards the United States, and had met with US officials in Washington in June 1983. Although Bishop then met with Castro early in October, hardliners in Bishop’s cabinet now decided to remove him from power. Cuban and Soviet backed Marxist revolutionaries, led by Deputy Prime Minister Bernard Coard and the Leninist General Hudson Austin, placed Bishop under house arrest during the night of 13 October.[xxi]

Spurred by counter-revolutionary broadcasts supporting Bishop from Radio Free Grenada, a mob began to form outside the government run newspaper office. By 18 October General Hudson’s government was in crisis, with five cabinet members, including foreign minister Unison Whiteman having resigned to join the pro-Bishop mob, now more than 1,000 protester strong.

On Wednesday, 19 October 1983, the mob, led by Whiteman, freed Bishop from his house arrest and proceeded to march towards Fort Rupert, the police headquarters, and the entry point to St. George’s harbor. At this point troops loyal to Bernard Coard and General Austin, including armoured personal carriers (APCs), surrounded the mob and opened fire. Bishop and his cabinet were arrested and marched to Fort Rupert where they were executed. 18 people altogether, including education minister Jacqueline Creft and others, were killed.[xxii] General Austin declared himself head of the new Revolutionary Military Council and imposed a 24-hour curfew, in addition to closing the island’s commercial airport at Pearl, Grenville, on the island’s east coast.[xxiii]

Bernard Coard, Deputy Prime Minister & General Hudson Austin, Chief of the People’s Revolutionary Army, from the Associated Press newsreel archive.

Fort Rupert being stormed by the coup forces. Soviet BMP armoured vehicles lead the charge to capture Maurice Bishop, who was shortly thereafter executed by the junta. From The Grenada Papers by Paul Seabury and Walter McDougall (1984).

On 20 October Tom Adams, the Prime Minister of Barbados, denounced the violence on Grenada, followed shortly by Prime Minister Eugenia Charles of Dominica.[xxiv] On 21 October it became known, at an OECS meeting held on Barbados, that the US was looking for a reason to intervene in Grenada, and would be willing to do so at the OECS’s behest. A written request for intervention was thus drawn up,[xxv] and on 21 October, Antigua, Dominica, St. Lucia and St. Vincent, supported by Jamaica and Barbados, agreed to respond militarily to the overthrow of Bishop.[xxvi]

Prime Minister Adams of Barbados formally appealed to President Reagan for US military intervention in Grenada on 23 October.[xxvii] The OECS’s eight point request for information was also sent to the US State Department.[xxviii]

Geographical map of Grenada and the Grenadines from 1990

Geographical map of Grenada and the Grenadines from 1990

Grenada’s Governor-General, Sir Paul Scoon, had long before requested American assistance towards countering the rise of Cuban guerrillas on the island. Indeed, fighters from all over the Eastern bloc had been arriving in Grenada, including operatives and technical personal from Cuba, Russia, North Korea, Libya, East Germany and Bulgaria.[xxix] Castro, himself a promoter of Bishop’s government, however, refused to further support Austin,[xxx] no doubt concerned about directly confronting the United States over the crisis.

The Cuban dictator did, however, despatch Colonel Tortolo Comas to organize defensive measures on the island. Colonel Comas’ force included 43 Cuban soldiers and 741 Cuban construction workers, many of whom were also army reservists.[xxxi] Comas organized the Cuban fighters into companies to resist American intervention and deployed Soviet quad 12.7 mm Anti-Aircraft guns around the island, also authorizing the blocking of the runway at Point Salines with heavy equipment.

The People’s Revolutionary Army

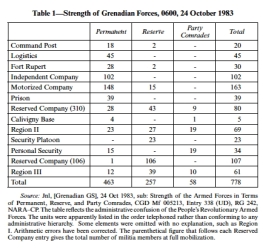

From Edgar F. Raines, The Rucksack War (2010). There were about 40 Cuban guerrillas fighters on Grenada, plus handfuls of fighters from the Soviet Union, North Korea, Syria and other Soviet bloc countries. There were 650 Cuban construction workers on the island, many of whom had military reservist training. The PRA was composed of a large battalion of soldiers, more than 450, supported by a small company sized militia.

19 October – 24 October: The Crisis & Planning

The Americans had become aware of the imminent possibility of action on 12 October. Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs, Langhorne A. “Tony” Motley, convened the Regional Interagency Group of the National Security Council (NSC),[xxxii] and Motley informed the representative from the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), Colonel James. W. Connally (USAF) – the Chief of the Western Hemisphere Division of the Plans and Policy Directorate – that the Pentagon should begin a planning process in the event a US evacuation were ordered and military support required.[xxxiii]

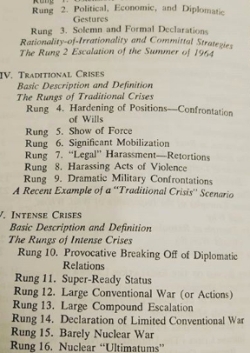

The rungs of “Traditional Crises” in Herman Kahn’s On Escalation (1965)

The rungs of “Traditional Crises” in Herman Kahn’s On Escalation (1965)

This started the ball rolling, and on 14 October the Latin American desk officer for the NSC, Alphonso Sapia-Bosch, got in touch with Commander Michael K. McQuiston, USN, at the Joint Operations Division (JOD), Operations Directorate (J3), who informed Lieutenant General Richard L. Prillaman, US Army, the Director of Operations, who in turn raised the problem of military intervention with the National Military Command Center. A crisis unit composed of officers from the Western Hemisphere Branch of the JOD, an officer J5, and a member of the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) were assembled to consider the possible program of operations.[xxxiv]

Meanwhile, on Barbados, the US Ambassador (also responsible for Grenada) began to receive reports of threats to the US medical students on Grenada. The NSC’s Regional Interagency Group met on 17 October to consider the ambassador’s reports, and, during this meeting, Assistant Secretary of State Motley asked Lt. General Jack N. Merritt (US Army), the Director of the Joint Staff, to prepare plans for a military rescue of the students. On 18 October Lt. General Merritt asked Lt. General Prillaman to contact Admiral Wesley L. McDonald (CINCLANT) to consider options.[xxxv] The group met again on 19 October, with Vice Admiral Arthur S. Moreau Jr., Assistant to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, in attendance.

The Deputy Director of the State Department’s Office of Caribbean Affairs, Richard Brown, briefed the group, specifically mentioning that at least 600 Cubans, mainly workers for the Point Salines airfield construction, were on the island, and two Cuban vessels were currently moored in St. George’s Harbor. At this point Vice Admiral Moreau pointed out that the JCS crisis unit was working on the problem, and that Lt. General Prillaman was monitoring the situation and in touch with USCINCLANT. It was decided to brief the Vice President (Special Situation Group) and the President (National Security Planning Group) to get authorization for military action.[xxxvi]

General John W. Vessey, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Admiral James D. Watkins, Chief of Naval Operations, 1982 – 1986

That evening Lt. General Prillaman sent Admiral McDonald the JSC Chairman’s warning order, requiring Admiral McDonald to submit plans covering various evacuation contingencies by the morning of the 20th. Readiness Command (USCINCRED) and Military Airlift Command (USCINCMAC) were to be in close touch with USCINCLANT. This planning group now requested DIA photoreconnaissance coverage of Grenada.[xxxvii]

As it happened, USLANTCOM had carried out rescue operation exercises involving Ranger and Marine landings in the Caribbean back in August 1981, and thus Admiral McDonald was able to reply speedily to the JCS, providing a full briefing to the Chairman later on the 20th. The need for higher resolution photography of Grenada, combined with better information on Grenadian forces (believed to number 1,200 regulars from the People’s Revolutionary Army (PRA), 2,500 – 5,000 militia, and four torpedo boats) was paramount.[xxxviii] It was known from DIA sources that a Cuban vessel (Vietnam Heroica) had delivered Cuban workers to the Point Salines airfield site, and that on 13 October more Cuban ships had delivered arms caches to the island.

Given the unknown nature of possible resistance on Grenada, the Atlantic Command staff recommended two general positions: first, diplomatic negotiations followed by civilian airlift of the hostages, if possible, or, in the event of opposition, the deployment of Marine Amphibious Ready Group (MARG) 1-84 and the USS Independence battle group, both in the process of transiting from the continental United States to Lebanon, with the possibility of a follow-on attack by multiple airborne forces from USREDCOM.[xxxix]

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, General Vessey, now briefed the Crisis Pre-Planning Group (CPPG) of the National Security Council, in a meeting chaired by Rear Admiral John M. Poindexter (USN), the Military Assistant to the NSC (and Bud McFarlane’s deputy). Also present were John McMahan, the Deputy Director of the CIA, and Lawrence S. Eagleburger, Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs, Assistant Secretary of State Langhorne A. Motley, the CIA’s Latin American specialist, Constantine Menges, and Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North.[xl] This meeting essentially passed the buck up to the Special Situation Group (SSG),[xli] although the lack of intelligence on Grenadian defences was discussed, with the CIA being requested to provide additional information. The CIA, however, had no agents actually in Grenada. Eventually the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) was contacted to provide immediate intelligence and, under this authorization, TR-1 and SR-71 overflights took place.[xlii] Although the results of these high-altitude reconnaissance missions were passed on to JSOC, they did not reach the assault force in time for the invasion.

At 6 pm on the 20th the Special Situation Group of the National Security Council was convened by the Vice President. Present at that meeting were Secretary of State George P. Shultz and General Vessey, who briefed Vice President Bush, the Secretary of Defense (Caspar Weinberger), the Director Central Intelligence (William Joseph Casey), the Counselor to the President (Edwin Meese), the President’s Chief of Staff (James Baker), the Deputy Chief of Staff (Michael Deaver), and the National Security Advisor (Robert McFarlane) on the Grenada situation. The Vice President approved an expanded mission including “neutralization” of the Grenadian forces, although both “forceful extraction” and “surgical strike” plans were also considered.[xliii] Both Casey and Shultz favoured an invasion followed by the restoration of democracy, a plan supported by the CIA’s Menges.[xliv]

The timeframe was an issue, as the forces diverted to Grenada were needed to relieve MARG 2-83 in Lebanon, while the naval forces were required for the CRISEX ’83 exercise to be held with Spain. Nevertheless, as evening fell on 20 October, orders were issued to divert the task force.

Combined Joint Task Force 120

At 3 am on October 21st MARG 1-84 started heading in the direction of Puerto Rico, while the CV-62 (USS Independence) group made for Dominica.[xlv] At 10 pm on 22 October orders were received for the entire force to combine near Grenada.[xlvi]

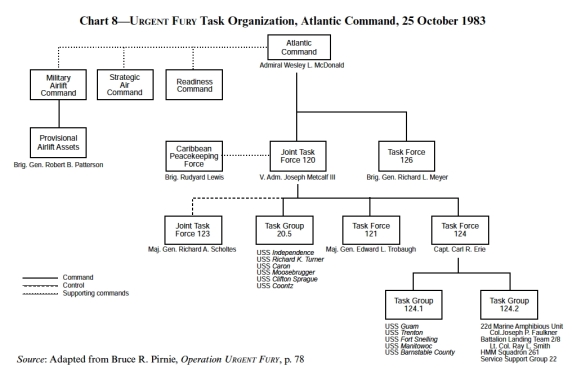

Organization Chart for Operation Urgent Fury, reproduced from Edgar Raines, The Rucksack War (2010).

Organization Chart for Operation Urgent Fury, reproduced from Edgar Raines, The Rucksack War (2010).

General Vessey was in contact with Admiral McDonald the morning of the 21st by which time it had been decided to add the two battalions of US Army Rangers and components of the 82nd Airborne Division to the invasion force. Vessey, due to attend a speaking engagement that evening, was briefly replaced by Admiral James D. Watkins the Chief of Naval Operations, to continue the planning processes. By now it was suspected that as many as 240 Cuban soldiers were on Grenada, plus as many as 50 Soviet citizens.[xlvii]

Vessey, about to depart for Chicago, contacted Atlantic Command, Military Airlift Command, Readiness Command and JSOC, instructing them to manage the deployment of Rangers, airborne and special operations forces to Grenada, in conjunction with the CINCLANT naval force deployments, all while maintaining operational secrecy and security. Grenada’s message traffic, being intercepted at the Pentagon, was, at Lt. General Prillaman’s behest, transferred to SPECAT (Special Category restrictions) channels. This was prudent, and helped to reduce later leaks, however, the story was nevertheless about to break: CBS had gotten wind of the Task Force diversion and ran the story on the 21 October evening news.[xlviii] Staff planners from the Rangers, JSOC, and 82nd Airborne were already aboard flights to Norfolk to meet with planners from the USMC, MAC and Atlantic Command headquarters.

Atlantic Command, Norfolk, Virginia. From Edgar F. Raines, The Rucksack War (2010). & Admiral Wesley L. McDonald, CINCLANT, October 1983

Meanwhile, Donald Cruz, the consular officer in Barbados, traveled to Grenada to meet with Major Leon Cornwall, a senior figure in the Revolutionary Military Council. Cruz met with the students at St. George’s university, who expressed concern about their situation. Cruz then departed by plane after it was cleared for Grenadian airspace.[xlix] At Bridgetown, Barbados, the OECS convened, and invoked Article 8 of the 1981 treaty, requesting the intervention of Barbados, Jamaica and the US in a multinational peacekeeping effort aimed at Grenada. Governor-General Sir Paul Scoon requested OECS support to liberate the island. These requests were relayed to the US State Department from Barbados between 21 and 22 October.

On the evening of the 21st Constantine Menges and Lt. Colonel Oliver North drafted an invasion order under the authority of a National Security Decision Directive for Reagan to sign. The order was sent to the President in Augusta, Georgia, but Reagan delayed.[l]

The Joint Chiefs of Staff, from Edgar F. Raines, The Rucksack War (2010). Vessey seated.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff, from Edgar F. Raines, The Rucksack War (2010). Vessey seated.

At 1:30 in the morning of 22 October, General Vessey returned to Washington, and the SSG was convened. At 4:30 am, as we have seen, the SSG phoned President Reagan, Secretary of State Shultz and National Security Advisor McFarlane, who were staying at the Eisenhower cottage at the Augusta Country Club in Atlanta. A teleconference was arranged for the complete National Security Planning Group at 9 am.[li] In that conference, Bush, Poindexter, McMahon, Motely, Menges and North consulted with Reagan, Shultz and McFarlane. By 11:30 am the NSC had reached a consensus decision on intervention.[lii]

The Joint Chiefs had prepared two force packages, utilizing combinations of Army Rangers and other JSOC elements (Team Delta and Navy SEALs), supported by a Marine Corps landing and 82nd Airborne assault. The primary objectives involved capturing the Port Salines and Pearls airfields, followed by capture of the Grenadian capital at St. George’s (including radio station, government buildings and police HQ), the St. George’s medical school, the Grand Anse beach, and then the Grenadian army barracks at Calivigny. All objectives would be secured within the first four hours. The airborne force would then deploy to consolidate and reinforce. D-Day would be Tuesday, 25 October, requiring an action decision no later than 8pm, 22 October.[liii] In fact, the decision for action and the order to carry out Urgent Fury had been issued at 4:45 pm.[liv]

President Reagan’s evening meeting with the National Security Council in the White House Situation Room, 23 October. George Shultz to Reagan’s left, Vice President Bush to his right.

When Reagan, Shultz and McFarlane arrived back in Washington on the 23rd, they discussed the Lebanon crisis and the Grenada operation. After discussing Lebanon, Secretary of Defense Casper W. Weinberger briefed Reagan on the Grenada plan. Reagan was wary of the risks, both to the medical students, and to the American forces. The Joint Chiefs assured the President that the the risks were marginal.[lv] Reagan signed the formal invasion order.[lvi] With the President’s approval, operation planning kicked into high gear. Secretary Weinberger authorized General Vessey to take control over of the operation, with the objective of speeding the decision cycle now that the political choice for action had been made.[lvii]

As with any action in the Cold War dynamic, American intervention in one hemisphere could prompt a Soviet response elsewhere. Reagan would brief Congress (under Section 3, War Powers Resolution) or inform Congress within 48 hours of the legality of the mission. The State Department would inform the United Nations Security Council and the Organization of American States regarding the justification for the invasion under UN Charter Article 51 and Rio Treaty Article 5. The United Kingdom would also be informed, considering Grenada’s status as a member of the Commonwealth. Shultz argued that Article 22 of the OAS and Article 52 of the UN charter, in addition to Prime Minister Eugenia Charles’ request for American assistance, provided the legal background for the intervention in Grenada.[lviii] With these issues outlined, new intelligence from the DIA (high-altitude reconnaissance) placed Grenadian and Cuban forces at as many as five thousand with eight Soviet made BTR-60 APCs and 18 ZU-23 anti-aircraft guns, in addition to 81-mm mortars and several 75-mm recoilless rifles located around the island.[lix] Grenada had no radar, ships or air units. The National Security Planning Group decided upon a maximum effort utilizing all available assets, and thus issued the Go order to Admiral McDonald.

After concluding his secure telephone call to Admiral McDonald, General Vessey contacted Strategic Air Command (SAC) and informed them of the operation. SAC immediately prepared KC-135 and KC-10 tanker aircraft to support the operation from Robbins Air Force Base, Georgia and Roosevelt Roads Naval Air Station, Puerto Rico. SAC also approved reconnaissance missions over the Eastern Caribbean.[lx]

On 23 October Secretary Shultz despatched Ambassador Francis J. McNeill, supported by Major General George B. Crist, USMC (future CENTCOM commander), the Vice Director of the Joint Staff, to meet the OECS representatives and determine their willingness to join in a peacekeeping force, coordinated by the State Department, the Joint Chiefs and the CIA.[lxi]

Meanwhile, Admiral McDonald’s staff revised the operational plan, now composed of four phases: Transit, Insertion, Stabilization/Evacuation, and finally, Peacekeeping. The US assault force would manage the first three phases, which essentially amounted to maneuver, special operations forces landing, full invasion, including US Marines, and pacification followed lastly by the OECS force being assembled to act in the constabulary role in the fourth phase during which an interim government would be created.[lxii]

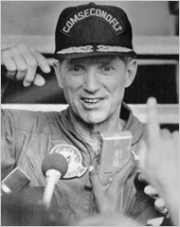

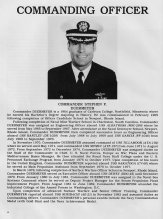

Admiral McDonald flew to Washington to brief the JCS on the evening of the 23rd. He proposed placing Vice Admiral Metcalf (CINC Second Fleet) in command of the Combined Joint Task Force 120.

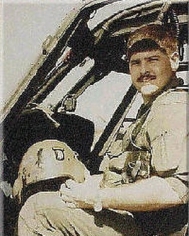

Vice Admiral Joseph Metcalf III, Second Fleet, Atlantic Command, selected to command Combined Joint Task Force 120, photographed here in October 1986. & Major General H. Norman Schwarzkopf (centre, as Lt. General I Corps in 1987) was assigned as the Army – Navy liaison for Atlantic command, and then appointed by Metcalf as the operation Deputy Commander.

The Joint Chiefs were aware that the Navy needed access to consultation from someone with experience commanding combined operations, including Rangers, Airborne and Marines, and decided to appoint an Army-Navy liaison to Metcalf’s staff. On the afternoon of Sunday, 23 October, Major General H. Norman Schwarzkopf, then the divisional commander of the 24th Mechanized Division, received a phone call from Major General Dick Graves, informing him that he was being considered for the position of Army – Navy liaison. Schwarzkopf soon discovered that this operation was the full-scale plan for the Grenada invasion.[lxxx]

List of USN warships involved in Operation Urgent Fury

List of USN warships involved in Operation Urgent Fury

The core of the CJTF was Task Group 20.5: the reinforced USS Independence (CV-62) battle group, commanded by Rear Admiral Richard C. Berry. Captain John Maye Quarterman Jr. in USS Guam (LPH-19) provided the base for amphibious operations and the flagship for Vice Admiral Metcalf. Amphibious Squadron Four itself was commanded by Captain Carl R. Erie (Task Force 124), with Commander Richard A. Butler as his chief of staff (Butler would later prove invaluable as one of the few naval officer in the squadron with knowledge of Grenadian waters).[lxvi] Captain David Bennett was also on hand in USS Saipan (LHA-2), part of Destroyer Squadron 24, in addition to two modern nuclear attack submarines (SSNs) amidst a host of destroyers, frigates and landing craft.

USS Independence, Air Wing CVW-6 and a Wichita-class refueler operating off Lebanon in December 1983.

USS Independence, Air Wing CVW-6 and a Wichita-class refueler operating off Lebanon in December 1983.

The JSOC force element, including Rangers, SEALs, Delta, and 160th Aviation Battalion pilots, was designated Task Force 123. JSOC had received the notice to prepare on 21 October.[lxvii] The MH-60A Black Hawk Helicopters from the newly formed 160th Aviation Battalion,[lxviii] composed of pilots selected from brigades of the 101st Airborne division, would lead the way in their battlefield debut. Delta Force and US Army Rangers, received orders to surge on 23 October, deploying to Barbados in C-5A aircraft before assembling their seven UH-60 helicopters.[lxix]

USS Independence (CV-62), Task Group 20.5, Carrier Group Four

Task Group 20.5 CO, Rear Admiral Richard C. Berry, photographed in 1983, to the left of Vice Admiral Edward Briggs (center), Commander US Surface Forces, Atlantic Fleet)

Task Group 20.5 CO, Rear Admiral Richard C. Berry, photographed in 1983, to the left of Vice Admiral Edward Briggs (center), Commander US Surface Forces, Atlantic Fleet)

The centrepiece of the USN task force was Carrier Group Four’s fleet carrier, USS Independence (CV-62), a 60,000 – 79,000 ton Forrestel class aircraft carrier.

CV-62 photographed alongside USS Savannah, (AOR-4), in the early 1980s. CV-62 CO, Captain William Adam Dougherty Jr. (seen here as Rear Admiral)

CJTF 120 was created on 23 October with Vice Admiral Joseph Metcalf, Second Fleet, appointed as Operation Urgent Fury’s commander. Metcalf’s amphibious force was designated Task Force 124, placed under the command of Captain Carl R. Erie, with attached 22nd Marine Amphibious Unit under Colonel James P. Faulkner.[lxiii] Additional elements included Task Force 121, which was comprised of components of the 82nd Airborne. Major General Edward Trobaugh, commander 82nd Airborne Division, had received the warning order on 22 October. The Division Ready Brigade at the time was 2nd Brigade’s three battalions, 2/325th, 3/325th, 2/508th, plus fire-support from B & C batteries 1/320th AFAB.[lxiv]

82nd Airborne Division, US Army

82nd Airborne troopers waiting to deploy for Operation Urgent Fury air assault, MSG Dave Goldie colleciton. & Major General Edward Trobaugh, CO 82nd Airborne Division.

B Company, 2nd Battalion, 505th, December 1983 in Grenada, reproduced in Stephen Trujilo, Grenada Raiders (2017). Major Edward Trobaugh’s 82nd Airborne Division’s Ready Brigade, three battalions of the 2nd Brigade, 2/325th, 3/325th, 2/508th and B & C batteries 1/320th AFAB.

B Company, 2nd Battalion, 505th, December 1983 in Grenada, reproduced in Stephen Trujilo, Grenada Raiders (2017). Major Edward Trobaugh’s 82nd Airborne Division’s Ready Brigade, three battalions of the 2nd Brigade, 2/325th, 3/325th, 2/508th and B & C batteries 1/320th AFAB.

Organization of the 82nd Airborne Division, with units then on readiness selected for Urgent Fury. From Edgar F. Raines, The Rucksack War (2010).

In addition to SAC and MAC air support, the USAF would provided Task Force 126: eight F-15s from the 33rd Tactical Fighter Wing and four E-3As from the 552nd Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) detachment, with the explicit objective of preventing Cuban interference around Grenada’s airspace.[lxv] General Vessey roughly determined that Grenada would be split into two areas of operation, with the north designated for the US Marines, and the south for all Army operation

Task Force 123

Joint Special Operations Command, 75th Infantry Regiment (Rangers), Team Delta, US Navy SEALs, 160th Aviation Battalion, 1st Special Operations Wing (USAF)

Major General Richard Scholtz, CO of JTF 123 and the first commander of JSOC. & Organization of Task Force 123, from Edgar F. Raines, The Rucksack War (2010). This was the first battlefield test of the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), created by Charlie Beckwith following the debacle during Operation Eagle Claw in 1979. The idea was to combine the US military’s elite special operations forces under a single tactical command, supported by specially trained helicopter pilots, enabling rapid insertion and exfiltration during hostage rescue and counter-terrorism missions.

The JSOC Ranger assault (1st Battalion, Lt. Col. Wesley Taylor) would drop or land in five C-130 aircraft, escorted by four helicopter gunships, and secure the airfield at Salines. The Rangers would then secure medical students at the True Blue campus, afterwards moving to support the capture of St. George’s. 2nd Battalion’s Lt. Col. Ralph Hagler would then deploy and lead an attack on the PRA barracks at Calivngy.[lxx] JSOC commander Scholtes notified the Rangers on 22 October, and informed them that due to the limitation in available night-trained C-130 pilots, the Rangers would have to manage the initial deployment with only 50% of their total force.[lxxi]

The Point Salines objectives were given to the Rangers’ 1st Battalion’s A Company, Captain John Abizaid – later CENTCOM commander – and B Company, Captain Clyde Newman. Total strength was 300, plus two 25-man HQ elements. The Calivigny assault, scheduled for dawn on D+1, was given to 2nd Battalion’s A Company, Captain Francis Kearney, B Company, Captain Thomas Sittnik, and C Company, Captain Mark Hanna. Each company captain was to select 50 or 80 Rangers for their portion of the mission.[lxxiii] Once the 1st Ranger Battalion had cleared the Point Salines runway, C-141 Starlifters would arrive with Team Delta’s Little Bird helicopters, deploy them, and then carry out an assault on Fort Rupert.[lxxiv]

Under the guise of a training exercise, the two battalions now mobilized at Hunter Army Air Field, Georgia, at 2 pm, 23 October.[lxxii]

1st SFOD-Delta, A & B Squadrons

B Squadron. Eric Haney in back with sunglasses, Grenada, October 1983; Eric L. Haney, author of the memoir Inside Delta Force (2002).

JSOC had a number of targets to hit: while the Rangers were capturing Point Salines, Team Delta’s B Squadron, flown in by Major Larry Sloan’s Black Hawk, would secure the Richmond Hill Prison,[xcii] and SEALs from Team 6 would land from Major Bob Johnson’s Black Hawks in St. George’s to capture the Governor’s residence (behind Fort Rupert at the harbour entrance) as well as the Beausejour radio station. Nearby, Fort Frederick would be plastered by USAF aircraft to prevent the PRA from intervening in the Richmond Hill attack.[xciii]

A Squadron operators on 25 October. Emerson “Mac” Bolen, Tommy Carter, John Turner, unknown, and Danny Pugh. Reproduced in Stephen Trujilo, Grenada Raiders (2017)

A Squadron operators on 25 October. Emerson “Mac” Bolen, Tommy Carter, John Turner, unknown, and Danny Pugh. Reproduced in Stephen Trujilo, Grenada Raiders (2017)

After the Rangers had taken Point Salines, Delta’s A Squadron would land its Little Bird helicopters via C-141s and make an airborne assault against Fort Rupert. Although JSOC possessed plenty of detailed maps, most were left behind in the scramble to mobilize: USS Guam had only a 1936 copy of an 1895 British nautical chart of the Island, and Guam’s only Xerox machine printed copies too small to be useful.[xciv] The Delta operators bought Michelin guide maps of the Windward Islands to make do.[xcv]

SEAL Teams 4 & 6

SEAL Team 4 operators in January 1990 during Operation Just Cause, the invasion of Panama. During Urgent Fury, Team 4 would carry out UDT reconnaissance of the Grenville – Pearls area.

SEAL Team 4 operators in January 1990 during Operation Just Cause, the invasion of Panama. During Urgent Fury, Team 4 would carry out UDT reconnaissance of the Grenville – Pearls area.

US Navy SEALs from Team 6 were scheduled to insert on the morning of the 23rd to provide beach reconnaissance for the planned Marine Corps and Ranger landing sites. Once cleared to land, the Marines would secure the medical school campus at the Grand Anse beach, while simultaneously securing the nearby town of Grenville and the Pearls Airfield – the island’s commercial airfield – [lxxv] SEALs from Team 6 would work with the Delta and Ranger assault force to secure inland objectives, beginning with Sir Paul Scoon, the Governor-General, held captive in his residence at For Rupert. Team 6 was also tasked with capturing Grenada’s radio station, and several other key targets including Fort Frederick, the Richmond Hill Prison, and the PRA training camp at Calivigny.[lxxvi]

1st Special Operations Wing (USAF)

Five AC-130 gunships (16th Special Operations Squadron) provided close air support for the landings at Salines as well as during the SEAL insertion at St. George’s. The Ranger elements were deployed from 10 C-130s and two MC-130Es flown by this wing. The USAF Combat Control Teams used as pathfinders for the Rangers were also attached.

Five AC-130 gunships (16th Special Operations Squadron) provided close air support for the landings at Salines as well as during the SEAL insertion at St. George’s. The Ranger elements were deployed from 10 C-130s and two MC-130Es flown by this wing. The USAF Combat Control Teams used as pathfinders for the Rangers were also attached.

22nd Marine Amphibious Unit, USMC

On 22 October the Marine officers in MAU-22 – Colonel Faulkner, Lt. Colonel Smith and Lt. Colonel Amos – met aboard Guam to discuss the expected Grenada operation, which they believed at this time would be essentially an evacuation mission, assuming of course that the mission was going to go ahead.[lxxvii] It was decided that Company D would be used for amphibious assault, Company E for air assault, with Company F in reserve, or for a landing at the Pearls airfield.[lxxviii] Intelligence also arrived detailing what information was known about the PRA and its Cuban and Soviet bloc advisers. Liaison officers from CINCLANT, flown out from Antigua in a CH-53s, arrived the following evening, carrying information concerning the mission planning and Vice Admiral Metcalf’s objectives.[lxxix]

Ray Smith (USMC), the regimental Lt. Colonel who was commander of the 2/8th Battalion Landing Landing team. Smith’s Marine Corps career spanned the Vietnam and Cold War. Lt. Col. Ralph Hagler (left), CO 2nd Ranger Battalion, 75th Infantry Regiment, Rangers, US Army, photographed on 3 November, reproduced in Stephen Trujilo, Grenada Raiders (2017)

Amphibious Squadron Four, the MAU’s parent naval component, had sailed from the continental US for the Mediterranean on 18 October, with orders to relieve the Marine battalions stationed in Lebanon. Amphibious Squadron Four included the 22nd Marine Amphibious Unit (MAU) embarked under the command of Colonel James P. Faulkner (USMC). The entire force consisted of 43 officers and 779 men. Lt. Colonel Ray L. Smith’s men composed the core Battalion Landing Team 2/8. Lt. Colonel Granville R. Amos commanded the Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron 261 (HMM-261) and the Service Support Group 22 was commanded by Major Albert E. Shively. The Marine companies were commanded by Captains Henry Donigan (E), Michael Dick (F), Robert Dobson (G).

Early on 24 October Major General Crist was meeting with the chiefs of staff of the defense forces of Jamaica and Barbados, as well as the OECS Regional Security commander, to iron out the contribution of the Caribbean Peacekeeping Force (CPF). It was determined that the CPF would deploy on the 25th, following the American assault, and would relieve US forces from holding key targets such as the Richmond Hill Prison, government buildings and the radio station in St. George’s. Jamaica was sending 150 troops, including a rifle company, an 81-mm mortar section and a medical team. Barbados contributed a rifle platoon of 50 soldiers, with the OECS unit comprising 100 constabulary personnel.[lxxxi]

Admiral McDonald called a meeting early in the morning on 24 October at Norfolk. In attendance were Vice Admiral Metcalf (CJTF 120), Major General Ed Trobaugh (82nd Airborne – TF 121), Major General Richard Scholtes (JSOC – TF 123) and Major General Schwarzkopf, in addition to representatives from the CIA and State Department. The atmosphere, following the loss of the Navy SEAL team at Salines (see below) was tense.[lxxxii] With less than 24 hours to go before the invasion was to commence, Major General Scholtes recommended a 24 hour delay so further reconnaissance could be carried out. This was denied, and a compromise was agreed instead, with Admiral McDonald pushing back H-hour from 2 to 5 am on the 25th, so that the Navy SEALs could take one more shot at Salines early on the 25th.[lxxxiii]

The attack plan as represented by Wikipedia, showing Ranger and 82nd Airborne Division drops, JSOC insertion, and USMC assaults; & Detail of the same, showing allocation of US forces and targets. The initial landings were centred around securing three primary objectives: the Point Salines airstrip, the Pearls airport at Greville, and the capital buildings at Saint George’s. There were a series of secondary targets, including colonial fortifications, the university campuses, army barracks, and the surrounding hillside.

Metcalf suggested placing Schwarzkopf in the position of ground commander once the amphibious landings had taken place, but he was overruled by McDonald who pointed out that Major General Trobaugh outranked Schwarzkopf.[lxxxiv] Schwarzkopf, for his part, wasn’t certain how much use his input would be on such short notice. Metcalf made another important decision at this point, designating four members of his staff to send half-hourly status reports back to CINCLANT- the idea being to outflank any media reports while also providing a concise narrative of event for the political and military leadership to follow as the invasion unfolded.[lxxxv]

At 11 am, after concluding this meeting, Vice Admiral Metcalf and Major General Schwarzkopf boarded an aircraft for the flight to Bridgetown, Barbados, to meet Major General Crist and Brigadier General Rudyard Lewis, the commander of the Caribbean Peacekeeping Force. Arriving at the Bridgetown airport amidst a flurry of journalists – expectations of imminent American military action having leaked out – and with Brigadier General Lewis not immediately available, Metcalf met briefly with Major General Crist instead, ordering him to organize the CPF for airlift to Pearls or Salines.[lxxxvi] Next, Metcalf, Schwarzkopf and their staffs transferred to Navy helicopters for the flight out to USS Guam, arriving between 5:30 and 5:45 pm while the Task Force was still several hundred miles from Grenada.[lxxxvii] The last of the task force arrived in Grenadian waters at 2 am on 25 October.[lxxxviii]

In Tampa, Florida, General Wallace Nutting, C-in-C Readiness Command (REDCOM) ordered the XVIII Airborne Corps to prepare the 82nd Airborne for deployment to Grenada, placing the deployed battalions under the command of Admiral McDonald.[lxxxix]

Black Hawk UH-60 helicopters, 160th Aviation Battalion photographed near Point Salines airfield, where 1st and 2nd battalions, 75th Ranger regiment, deployed on 25 October. SPC Douglas Ide collection.

Black Hawk UH-60 helicopters, 160th Aviation Battalion photographed near Point Salines airfield, where 1st and 2nd battalions, 75th Ranger regiment, deployed on 25 October. SPC Douglas Ide collection.

The Black Hawk helicopters of Colonel Terrence “Terry” M. Henry’s 160th Aviation Battalion, five from Charlie 101 and four from Charlie 158 – both technically 101st Airborne Division components, were being loaded aboard C-5A aircraft on the evening of 23 October. The battalion’s helicopters were being flown to Barbados, along with more than 100 SEALs and Delta operators, 45 pilots and crews for the helicopters, and a handful of CIA and State Department officers.[xc] The Black Hawks would be led by pilots Major Robert Lee Johnson and Major Larry Sloan.[xci] The fully loaded C-5As took off from Pope Air Force Base on the evening of the 24th, and after landing in Barbados early on the 25th were ready to launch an hour before the sun was due to rise.

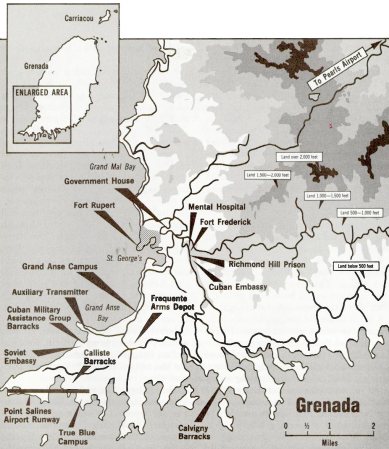

Detailed western targets, ie, not including Grenville and the Pearls Airport. During Operation Urgent Fury maps of Grenada were scarce. This was the result of short-timing and lack of local sources in the CIA and State Department. Estimates about force locations were often wrong and enemy skill with machine guns and anti-aircraft guns was underestimated, proving a real threat to Special Operations Forces helicopters and light infantry.

Forts overlooking St. George. Fort Rupert/Fort George at harbour entrance in green, Fort Frederick & Fort Mathew in red and the ruins of Forts Lucas and Adolphus in blue. Richmond Hill Prison in purple.

24 October, President Reagan holds a briefing with the National Security Council to discuss Lebanon. Present are: National Security Advisor Robert McFarlane, John Poindexter, James Baker, Ed Meese, Michael Deaver, David Gergen, Larry Speakes, Richard Darman, Ken Duberstein, Craig Fuller, and George H. W. Bush.

At noon on 24 October President Reagan met individually with the Joint Chiefs at the White House, who again expressed their belief in the success of the operation. Secretary of Defense Weinberger, General Vessey and the other Joint Chiefs met with Secretary of State Shultz and the President to brief Congressional leaders. After the meeting the President and the rest of the National Security Council met with National Security Advisor McFarlane who had converted the Situation Room into a War Room to receive Metcalf’s staff reports from Grenada. Reagan asked Vessey what he intended to do. General Vessey said he planned to telephone the Pentagon with the final authorization and then go home and go to sleep.[xcvi]

PART TWO

Reconnaissance, 23 – 24 October

View of St. George’s harbour with Fort Frederick complex overlooking the Richmond Hill Prison, and Fort Rupert at right.

The Navy SEALs of Team 6 carried out the first JSOC mission. 12 SEALs and four members of an Air Force Combat Control Team (CCT) were sent in to reconnoiter the proposed beach landing site at Salines early on the morning of the 24th. The crews and their Boston whaler boats were parachuted into the water south of Grenada, near where USS Clifton Sprague was operating. The mission called for the crews to go ashore at Point Salines and carry out beach reconnaissance while the CCT operators planted radio beacons at the airfield for the C-130s to hone in on during the Ranger drop.[xcvii] This was a dangerous, complex, and untested mission and the results were poor.

The weather and sea conditions were not favourable, with the result that four of the SEALs drowned – either when their boat overturned or as a result of the drop. When the remaining SEALs and CCT men headed towards the shore in their only boat, the boat was swamped by waves and the engine flooded. Dawn was breaking by the time the SEALs were nearing the shore, and, for fear of revealing themselves and thus compromising the mission, the SEALs headed back out to sea, meeting up with Clifton Sprague.[xcviii]

Cuban construction workers on the Point Salines airfield, from the Grenada Papers (1984). & View of the unfinished terminal buildings at the Salines airport

Various SOF missions during the Grenada campaign. The failed Team 6 mission for 24 October was the Salines beach reconnaissance. The Paul Scoon rescue mission occurred on 25 October, as did the Beausejour radio tower mission. The first SEAL Team 6 mission to Salines (failed) is not listed. The 1st SOW mission for 25 October was the USAF Combat Control Team pathfinder jump.

Patrol Boat Light (PBL)-type Boston whaler, improved variant of the single-engine type airdropped with Team 6 crew for the Salines mission.

Second, after meeting with Metcalf aboard USS Guam, a SEAL Team 4 crew attached to Amphibious Squadron Four and commanded by “Wild” Bill Taylor and Lieutenant Michael Walsh, departed USS Fort Snelling at 10 pm on 24 October in the SeaFox patrol-boat. Once near Pearls the SEAL crew took to their Zodiac boats and carried out a traditional frogman UDT mission at the Pearls airport landing site,[xcix] successfully examining Grenville’s beaches. Considering the unfavourable nature of the terrain, the SEALs recommended a helicopter assault rather than a shore landing, and this change in plans was approved by Captain Erie and Vice Admiral Metcalf, only a few hours before the beginning of the invasion.[c] Afterwards, with the invasion underway, the Team 4 crew exfiltrated, eventually making their way to Guam to brief Schwarzkopf on the mission outcome.[ci]

SeaFox patrol boat used by the SEAL Team 4 crew as part of the Pearls airfield reconnaissance mission. Note Zodiac inflatable boat.

While SEAL Team 4 was beginning their mission, around midnight on the 24th, a second SEAL Team 6/CCT insertion was attempted at Salines, but again the whaler boats were swamped and the engines flooded. The operators, no doubt exhausted, were unable to reconnoitre the Salines beachhead before sunrise.[cii] The failure of the Team 6 insertion, and the loss of four SEALs during the unit’s first wartime operation since its inception, has generated considerable controversy, especially considering the relative success of the more traditional Team 4 mission at Grenville.

Although there was another Team 4 crew available at Puerto Rico, who theoretically could have been inserted by one of the Task Force’s two nuclear attack submarines (SSNs), hindsight is 20/20 and there almost certainly would not have been time for such a diversion.[ciii] Regardless of the exact details, the failure at Point Salines impacted not only mission planning – with Salines being deemed too dangerous for an amphibious landing – but also delayed the entire operation, with the Ranger’s C-130 drop pushed back twice from the planned 3 am launch to 5 am, only a dozen minutes before the sun began rising.[civ]

Helicopter Assault, 25 October

Guam in October 1983 off Grenada & Dr. Robert Jordan’s photograph of Guam seen from Grenada on 25 October, reproduced in Stephen Trujilo, Grenada Raiders (2017)

The Marines destined for Grenville were awaken at 1 am.[cv] The first 21 helicopters from Lt. Col. Amos’ HMM-261 element left USS Guam at 3:15 am.[cvi] Rain caused some delays, and thus the first components of Company E, carried in CH-46s with AH-1 Cobra escort, arrived at LZ Buzzard – south of Pearls – 30 minutes behind schedule.[cvii] A TOW equipped jeep was damaged during its deployment from a CH-53, and two marines broke arms or legs while unloading, but otherwise the deployment went off successfully.[cviii] 12.7-mm AA cannons fired on the incoming helicopters waves, but these guns were knocked out by Cobra gunships.[cix]

Sikorsky R(C)H-53 Sea Stallions, a Boeing-Vertol CH-46 Sea Knight and Bell UH-1N Iroquois on Guam‘s flight deck during Operation Urgent Fury. & CH-53 Sea Stallion helicopters deploying, SGT M. J. Creen’s collection

CH-46 Sea Knights on 25 October 1983. UH-60 landings at Salines during Operation Urgent Fury.

The helicopters delivered their Marines ashore at the Pearls airport at 5 am. Captain Henry Donigan, CO of Company E, deployed one platoon to secure the landing zone perimeter while the other two platoons attacked the airfield itself.[cx] Within two hours both the airfield and the Grenville objectives had been secured; the Marines captured two Cuban airplanes and their crews in the process.[cxi]

Lt. Colonel Smith was soon ashore with his HQ group, and he ordered the capture of Hill 275 that overlooked the airfield. The Grenadians had emplaced two 12.7-mm guns on the hill, but the crews fled as the Marines approached.[cxii] Company E now began moving west, encountering scattered 81-mm mortar fire in the process.

Marines landing at the Pearls airport, Grenville, 25 October, from Edgar F. Raines, The Rucksack War (2010).

Marines landing at the Pearls airport, Grenville, 25 October, from Edgar F. Raines, The Rucksack War (2010).

At 6.30 am the assault on Grenville began, with helicopters landing Company F at a soccer field, identified at LZ Oriole.[cxiii] In the case of both landings the initial landing zones had been less suitable than hoped, requiring quick adaptation by the helicopter pilots. Grenville and the port area were quickly secured without opposition, the population both friendly and excited to see the arriving Marines.

Black Hawks touching down on 25 October, SGT Michael Bogdanowicz. & UH-1N hovering 25 October, SPC Gregory Tully collection

On the west coast the Navy SEALs and Team Delta were about to hit their targets. Most of Team 6 was landed outside St. George’s to secure Sir Paul Scoon at the Governor’s residence, while one squad hit Grenada’s public radio station north of the capital. Fifteen SEALs, including Lieutenant Wellington “Duke” Leonard, Lt. Bill Davis, and Lt. Johnny Koenig, fast-roped successfully down to the residence. After deploying its SEALs, the command Black Hawk piloted by Major Robert Johnson and carrying Team 6 CO Captain Robert Gormly as well as the satellite radios, was hit by anti-aircraft fire. The helicopter’s instrument panel was blown to pieces and Johnson was badly wounded, forcing the co-pilot, Chief Warrant Officer David “Rosey” Rosengrant to fly back to Guam.[cxiv] Indeed, the Grenadians and Cuban gunners manning the anti-aircraft and machine guns covering the St. George’s approach were putting up a tremendous fire at the approaching helicopters.[cxv]

The Governor-General’s residence behind Fort Rupert, in St. George’s, from Edgar F. Raines, The Rucksack War (2010).

The Governor-General’s residence behind Fort Rupert, in St. George’s, from Edgar F. Raines, The Rucksack War (2010).

The SEALs persevered and successfully entered the Governor-General’s residence, locating Sir Paul with his family hiding in the building’s basement.[cxvi] The SEALs were shortly surrounded by Grenadian forces, including three BTR-60 APCs.[cxvii] The besieged SEALs were able to communicate to the fleet using their short-range radios, and, through Guam, SEAL Team 6 commander Gormly, who was about to head for Point Salines, was able to call for AC-130 gunship support. Metcalf despatched four Cobra gunships,[cxviii] and the Grenadian APCs were shortly out of commission.[cxix] The other telling is that Lt. Bill Davis used a phone in the Governor’s residence to call, “the airfield where American forces were already in control [Salines], and asked for gunship protection…”.[cxx] At any rate, with gunship and Cobra support, the SEALs held off the Grenadian infantry until the following morning when the Marines reached the Governor-General’s residence (see below).

Two teams of SEALs – 12 operators total – commanded by Lt. Donald K. “Kim” Erskine had also landed by MH-60 Pavehawks in a field next to the radio transmitter at Cape St. George Beausejour.[cxxi] Although the SEALs quickly overwhelmed the local guards at the Soviet built radio transmitter, PRA reinforcements, including a BTR-60, arrived and a firefight commenced.[cxxii] The SEALs lacked communication with the fleet (their cryptographic satellite radios did not work as planned, and their short range sets were too short range), and, worse, did not possess any anti-tank weapons.[cxxiii]

Radio Free Grenada, from Edgar F. Raines, The Rucksack War (2010).

Radio Free Grenada, from Edgar F. Raines, The Rucksack War (2010).

At about 2:30 pm, with ammunition nearly exhausted, Lieutenant Erskine retreated under fire. Although many of his SEALs were wounded, they managed to make it to the waterfront.[cxxiv] As the Navy called in airstrikes and naval gunfire on the transmitter,[cxxv] Erskine’s teams swam along the shoreline until they reached a rocky cliff-face and hid there. Two pairs of swimmers were despatched to commandeer local fishing boats, but the SEALs were unable to free the boats from their fishing lines. Eventually the SEALs all made for the open ocean, where they were luckily spotted by a C-130 aircraft early on the 26th, and thence retrieved by USS Caron.[cxxvi] Lt. Erskine received the Silver Star.

USS Caron firing on the Beausejour radio station after exfiltration by SEAL Team 6

USS Caron firing on the Beausejour radio station after exfiltration by SEAL Team 6

While the SEALs were carrying out these operations, Delta’s B Squadron and components of Ranger C Company (1st Battalion) and their five Black Hawk helicopters were moving to their target. As the Black Hawks neared their objective at Richmond Hill they encountered heavy anti-aircraft and machinegun fire from Fort Frederick. Delta operator Eric Haney recalled his Black Hawk being hit by 23-mm rounds, wounding many of the occupants, including Major Larry Sloan, the commander of this Black Hawk section, who was hit in the shoulder and neck by 23-mm fire.[cxxvii]

Richmond Hill Prison, atop Mount Cardigan, west of Fort Frederick & Mathew. The tip of Point Salines (end of the airstrip) is visible at the extreme left.

When they reached the Richmond Hill prison the Rangers and Delta operators were stunned to find the target deserted. The helicopters thus broke off the attack, heading back out to the fleet to repair, refuel, and drop off wounded. As they were departing, one of the Black Hawks (#5), was hit by 23-mm rounds, the shells exploding through the cockpit windshield and killing the pilot, Captain Keith Lucas.[cxxviii] The Black Hawk went down inshore at 6:45 am near Amber Belair Hill. Although the crew, Rangers, and Delta operators aboard were badly injured, they were able to hold off a Cuban patrol until a rescue team led by Steve Ansley arrived.[cxxix] The UH-60 that Delta team member Eric Haney was in made an emergency landing on USS Moosbrugger.[cxxx]

While attempting to repair aboard the Navy’s warships the 160th Aviation Battalion was encountering the sharp end of inter-service bureaucracy: the Navy comptroller in Washington cabled Guam instructing Metcalf not to refuel the Army’s helicopters due to budgeting issues between Army and Navy logistics.[cxxxi] “This is bullshit,” Schwarzkopf recalled Metcalf saying, “give them fuel.”[cxxxii]

Those uninjured in Delta’s B Squadron flew back to Grenada to support the Rangers, and the Delta operators landed at Point Salines, moving into the hills around the airstrip to try to disrupt the 23-mm AA cannons before the Rangers began their C-130 airdrop.[cxxxiii]

SEAL Team 6 CO Captain Bob Gormly and Delta Deputy Commander Lt. Commander “Bucky” Burruss at Point Salines, during Urgent Fury & LTC Burruss with LTC John “Coach” Carney, USAF Combat Controller.

The Airdrop

A Company’s Rangers departed the airfield in Georgia at 11:30 pm on 24 October.[cxxxiv] The Pathfinders were over the target at 3:30 am and jumped from a reconnaissance C-130 at 2,000 feet. On the ground, they confirmed that the Salines’ runway was blocked.[cxxxv] As the Rangers were preparing for the airdrop, Col. Taylor was unable to communicate with all of the aircraft in the formation, the lead aircraft’s navigation instruments were malfunctioning, and there were no radio beacons to hone in on. Taylor’s executive officer, Major Jack Nix, in transport #5, anticipated the jump order.[cxxxvi] Due to conflicting orders, some of the Rangers were stowing their chutes when they received a twenty minute warning that they were in fact jumping.

Major General Scholtes, who was airborne in a command EC-130, delayed the drop by thirty minutes to 5:30 am.[cxxxvii] Although a specialist team of heavy machinery operators from the 82nd Airborne Division’s 618th Engineering Company were supposed to drop first and clear the runway, the C-130 they were in was forced to fall back, putting Lt. Col. Taylor’s aircraft in the lead.[cxxxviii]

Photograph taken by Ranger during airdrop at Point Salines

Photograph taken by Ranger during airdrop at Point Salines

Photograph by Tom Tassakis of Rangers dropping on Point Salines, reproduced in Stephen Trujilo, Grenada Raiders (2017)

Photograph by Tom Tassakis of Rangers dropping on Point Salines, reproduced in Stephen Trujilo, Grenada Raiders (2017)

With dawn breaking and sky conditions partly cloudy, the 1st Battalion Rangers began their drop at Salines at 5:34 am. Immediately the aircraft were lit by PRA searchlights and then fired upon by quad 12.7-mm fire.[cxxxix] Once on the ground Lt. Col. Taylor and nearby B Company Rangers watched two of the C-130s curve away, having aborted their drop due to intense AA fire. With only 40 men on the ground, Taylor called in AC-130 support, with two gunships responding. The Rangers hurried to clear the airfield of debris and vehicles. At 5:52 A Company’s Rangers started their drop, and were assembled on the ground by 6:34 am.[cxl] The Rangers, leading an infantry charge, quickly cleared the enemy guns from the airfield and then commandeered a local bulldozer to clear the runway. Colonel Taylor’s force was fully deployed within the hour.

Airdrop, 25 October, from Edgar F. Raines, The Rucksack War (2010).

Airdrop, 25 October, from Edgar F. Raines, The Rucksack War (2010).

At 7:07 am 2nd Battalion began its drop, and sustained several casualties in the process: Sergeant Kevin Joseph Lannon and Sergeant Phillip Sebastian Grenier were dead when they hit the ground.[cxli] Specialist Harold Hagen broke his leg, and Specialist William Fedak was tangled exiting the C-130, but was recovered aboard the plane.[cxlii]

Private Mark Yamane, M60 machine-gunner in A Company, was killed by a shot through the neck while providing fire behind a truck on the tarmac. 1st Battalion was in an extended gunfight with the Cuban defenders, more than 75 of whom eventually surrendered.[cxliii] The Rangers moved out to secure the village of Calliste.[cxliv]

Salines, showing the approach and runway, from the air. Department of Defense photograph of objectives at the incomplete Salines airfield

The Rangers reached the medical school’s True Blue Campus at 7:30 am, and the building was secured after a firefight lasting 15 minutes. The PRA guards fled to the north. While conducting a jeep reconnaissance around True Blue, Sergeant Randy Cline of A Company (1st Battalion) drove into a PRA Ambush, and Cline, Privates Marlin Maynard, Mark Rademarcher and Russell Robinson were all killed.[cxlv]

By 9 am the Rangers had rescued 138 of the American medical students who were being held at the True Blue Campus, and learned that there were another 200 students being held at the Grand Anse beach campus. In total 250 Cubans had by now been captured, however the assault force lacked translators to interrogate the prisoners.[cxlvi]

2nd Ranger Battalion soldiers cover captured Cuban prisoners at the Salines airfield, reproduced in Stephen Trujilo, Grenada Raiders (2017)

2nd Ranger Battalion soldiers cover captured Cuban prisoners at the Salines airfield, reproduced in Stephen Trujilo, Grenada Raiders (2017)

Delta operator overlooking Task Force 160s UH-60s and OH-6s, which had been flown in aboard MAC transports to the cleared Salines airfield during Urgent Fury

Delta operator overlooking Task Force 160s UH-60s and OH-6s, which had been flown in aboard MAC transports to the cleared Salines airfield during Urgent Fury

While B Company’s Rangers were securing the airport, Team Delta’s A Squadron was deploying at Salines by C-141s. A Squadron set off in their Little Bird helicopters to attack Fort Rupert, but was forced to abandon the assault due to heavy AA fire.[cxlvii] 2nd Battalion (Rangers) were meanwhile preparing for the Calivigny operation, consolidating their hold on the Salines airfield, while C-130s landed equipment and Major General Scholtes established his HQ.

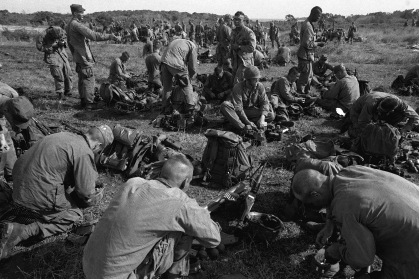

Prepared 82nd Airborne trooper, photograph by JOC Gary Miller collection, 28 October, & 82nd Airborne deploying for Grenada operation, SPC James Hefner

At 10 am the 2nd Battalion of the 2nd Brigade, 82nd Airborne, began their C-141 airlift from Fort Bragg to Point Salines. The Airborne troopers, beginning with A Company, 2nd Battalion, landed at 2:05 pm.[cxlviii]

Advance from Salines, 25 October, from Edgar F. Raines, The Rucksack War (2010).

Advance from Salines, 25 October, from Edgar F. Raines, The Rucksack War (2010).

Vice Admiral Metcalf meanwhile was deploying the CPF to Point Salines to help reinforce the assault forces, and, along with General Crist, the CPF began landing at 10:45 am.[cxlix] CPF commander Brigadier General Lewis met with Major General Scholtes and Major General Trobaugh and agreed to use the CPF units to guard the Cuban prisoners.

Brigadier General Rudyard Lewis of Barbados, commander Caribbean Peacekeeping Force (CPF), 25 October 1983 by JO1 Sundber

Brigadier General Rudyard Lewis of Barbados, commander Caribbean Peacekeeping Force (CPF), 25 October 1983 by JO1 Sundber

Eastern Caribbean Defence force soldiers board a Black Hawk helicopter on 25 October, Creen collection. Eastern Caribbean Defence (ECD) force soldiers, by PH2 D. Wujcik.

The Ranger’s final action at the Salines runway occurred at 3:30 pm when three BTR-60s attempted to break through a section of the line held by 2nd Platoon, A Company. Two of these APCs were quickly knocked out by LAW and 90-mm recoilless fire; Sergeant Jimmy Pickering is credited with the 90-mm hits.[cl] The third BTR, which had attempted to flee, was destroyed by AC-130 gunship fire.[cli]

Knocked out Grenadian BTR-6. & C company, 1st Battalion, 75th Infantry Regiment (Rangers) on 25 October, at Point Salines

Cobras Down

As we have seen, earlier in the day SEALs from Team 6 attempted to rescue Governor-General Paul Scoon. The SEALs had quickly secured Scoon but where then pinned down by APCs.[clii] The Rangers who were supposed to support the SEALs were busy fighting what they thought was a Cuban battalion north of Salines. Metcalf ordered airstrikes around the Governor-General’s residence to hold off the Grenadian forces.

Four Cobra gunships – in addition to a 1st SOW USAF AC-130 gunship – were tasked to provide this support, but the Cobras were low on fuel and unable to communicate with the Army or Air Force ground coordinators outside St. George’s. While Captains John P. “Pat” Giguere and Timothy B. Howard were heading to Guam for refueling, Captains Douglas J. “Darth Flight” Diehl and Gary W. Watson were just about finished their own refuelling and ready to depart. As the Cobras were heading back to Grenada, Captain Watson managed to establish radio contact with a forward air controller from the 1st Ranger Battalion, who wanted the Cobras to attack a 75-mm recoilless gun positioned inside a house near St. George’s. Watson destroyed the target and a nearby truck with two TOW missiles.[cliii]

AH-1 Sea Cobra in flight, 25 October, PH2 D. Wujcik collection, & HMM-261 AH-1S Cobra firing its 20mm cannon, 25 October, MSGT David Goldie

Watson and Diehl headed back for Guam, to re-arm and re-fuel, as Giguere and Howard had finished fueling and were again flying out to replace them on station. Now in touch with the ground air controllers, Giguere and Howard received a request to attack Fort Frederick, overlooking St. George’s. While the two Cobras were carrying out this strike, Captain Howard’s Cobra was hit by anti-aircraft fire, shells blowing out his engines and wounding both Howard and his co-pilot, Captain Jeb F. Seagle, who was knocked unconscious. With leg broken and arm injured, Howard brought the Cobra down on a soccer field.[cliv]

LTC Marshall Applegate photograph of SeaCobra supporting 1st Rangers at Salines, reproduced in Stephen Trujilo, Grenada Raiders (2017)

Seagle, who had regained consciousness, pulled Howard from the crash only moments before the Cobra exploded, setting off the gunship’s 2.75-inch rockets. Howard gave Seagle his pistol and the co-pilot set off to find help while Howard tried to radio for rescue, sporadic fire from Fort Frederick landing around him. Unbeknownst to Howard, Captain Seagle was killed by enemy fire not long after departing the crash site.

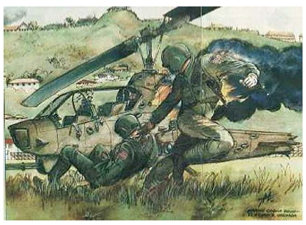

Captain Jeb Seagle drags Captain Timothy Howard from their downed Cobra gunship, although Howard was rescued, Seagle was killed. Art by Lt. Colonel A. M. Leahy.

Captain Jeb Seagle drags Captain Timothy Howard from their downed Cobra gunship, although Howard was rescued, Seagle was killed. Art by Lt. Colonel A. M. Leahy.

Burning wreck of Captain Howard’s Cobra at Tanteen field, reproduced in Stephen Trujilo, Grenada Raiders (2017)

Burning wreck of Captain Howard’s Cobra at Tanteen field, reproduced in Stephen Trujilo, Grenada Raiders (2017)

Howard’s wingman, Captain Giguere, was able to hold off Grenadian reinforcements moving to the crash site with rocket fire, while he radioed for a CH-46 to come pick up the survivors. CH-46 pilots Major DeMars and First Lieutenant Lawrence M. King Jr. made the approach, landing under fire near Howard. Gunnery Sergeant Kelly M. Neidigh jumped from the helicopter and with the aid of Corporal Simon D. Gore, Jr., rescued Howard. The CH-46 took off and headed for Guam.[clv] Tragically, Captain Giguere’s Cobra, which had been flying protection for the CH-46 during this time, was now hit by AA fire coming from the forts, and crashed into the harbor of St. George’s, killing Giguere and his co-pilot, First Lieutenant Jeffrey R. Scharver.[clvi]

Dr. Robert Jordan’s photograph of Captain Giguere’s Cobra crashing, taken from the Medical School. Major Melvin DeMar’s CH-46 is evacuating Captain Howard at the left. Major DeMar & Gunnery Sergeant Kelly Neidigh received Silver Stars for this action, reproduced in Stephen Trujilo, Grenada Raiders (2017)

Dr. Robert Jordan’s photograph of Captain Giguere’s Cobra crashing, taken from the Medical School. Major Melvin DeMar’s CH-46 is evacuating Captain Howard at the left. Major DeMar & Gunnery Sergeant Kelly Neidigh received Silver Stars for this action, reproduced in Stephen Trujilo, Grenada Raiders (2017)

Vice Admiral Metcalf now authorized the destruction of Fort Frederick. “Bomb it” agreed Schwarzkopf.[clvii] A-7 Corsairs from Independence were ordered to strike the forts. When Fort Frederick was bombed at 3:25 they inadvertently also destroyed what was in fact a mental hospital that had been fortified by the Grenadians, killing 18 of the patients who were locked in one of the hospital rooms when the airstrike occurred.[clviii]

A-7 Corsair overflying the Salines airstrip. Photograph by Gunnery Sergeant Joe Muccia. reproduced in Stephen Trujilo, Grenada Raiders (2017)

A-7 Corsair overflying the Salines airstrip. Photograph by Gunnery Sergeant Joe Muccia. reproduced in Stephen Trujilo, Grenada Raiders (2017)

Amphibious Landing

The assault forces would now direct their efforts towards securing St. George’s. At 12 pm, Vice Admiral Metcalf met with Major General Schwarzkopf to discuss the situation. Schwarzkopf recommended a landing north of St. George’s at Grand Mal Bay by the Marine forces that were currently loaded in their amphibious transports but not yet deployed (Company G).[clix] This would create a flank to draw away PRA forces from the Grenadian capital.[clx]

Marines disembarking from landing craft, 25 October.

Marines disembarking from landing craft, 25 October.

Lieutenant Colonel Smith, who was ashore at Grenville, was having difficulty communicating with Guam. At 3 pm he received word from the Fort Snelling that an amphibious landing was being planned for the Grand Mal Bay. Smith departed for Guam in a helicopter, where he was briefed by Major Van Huss.

UH-1 Iroquois landing amongst Marines, JOC Gary Miller collection & Marines with M16A1 rifles secure a housing complex on 25 October, photograph by PH2 D. Wujcik

The plan so far called for Captain Robert K. Dobson’s Company G to make the amphibious landing, while Company F would redeploy by helicopter from Grenville.[clxi] Smith convinced Metcalf and Schwarzkopf to delay the landing from 4:30 to 6:30, which meant recalling Company G – in the process of deploying to their landing craft from Manitowoc.[clxii] Navy SEALs hit the beaches and carried out a rapid beach reconnaissance.[clxiii] Dobson’s company had been sitting in its amphibious tractors since 3:45 am, their landing having been delayed four times until scrubbed at 7:30 am.

Still expecting to land at Pearls, Dobson was notified of the change in plans at 1:30 pm. USS Guam and the other amphibious ships were moving from the Pearls area to the west coast of the island for staging against Grand Mal Bay. Dobson, assuming the mission would be delayed until the following morning, at 5:50 pm had his marines prepare to stow their weapons and get some rest. Immediately after issuing this order the Go order was received for the Grand Mal Bay landing – designated LZ Fuel – at 6:30 pm.[clxiv] The first AAVs (amtracs) were ashore at 7:10 pm.

Marine drinking from a coconut, photograph by PH2 D. Wujcik, 25 October & US Army Rangers at Point Salines airfield on 26 October

Captain Dobson had his platoons establish a perimeter while conducting reconnaissance of the road south towards St. George’s. At 11 pm the Marines established a helicopter LZ, enabling the MAU air liaison Major William J. Sublette to land in a UH-1. Sublette briefed Dobson on the situation, informing the Company G commander that it was believed there were significant enemy forces between their location and the capital. Company F was scheduled to arrive within the hour by helicopter. Sublette headed back to Guam to pick up Lt. Colonel Smith, who had been trying to coordinate the situation between Pearls and the fleet for several hours, and now came ashore by CH-46.[clxv] Smith ordered Sublette to return to Pearls and contact Lt. Colonel Amos, who would organize Company F for immediate deployment to LZ Fuel.[clxvi]

Smith now briefed Company G on the situation, utilizing a detailed map of Grenada that had been captured at Pearls.[clxvii] Tanks, jeeps with TOW missiles, and Dragon anti-tank missiles were arriving aboard utility landing craft. At 4 am on the 26th Company F began to arrive by helicopter. Company G was making its way south towards St. George’s, encountering only sporadic RPG fire as the PRA soldiers, hearing the approach of Marine armor, fled their positions.[clxviii]

US serviceman shaving, 25 October, by SGT Michael Bogdanowicz

US serviceman shaving, 25 October, by SGT Michael Bogdanowicz

CV-62 under combat conditions during Operation Urgent Fury. Hundreds of sorties were flown, missions including strike, medievac, reconnaissance, anti-submarine and close air patrol.

D-Day + 1, 26 October