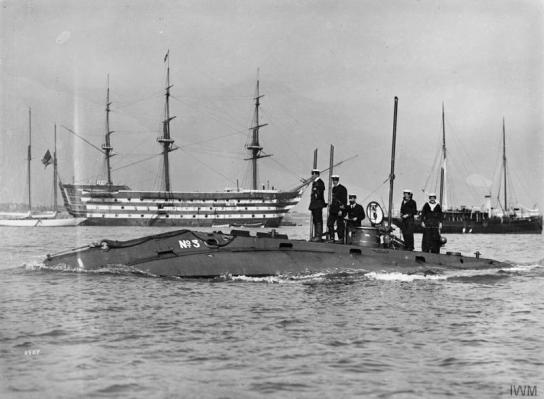

The day is coming! Unterseeboot before London. Lithograph print.

Unrestricted Submarine Warfare, 1917 – 1918

Introduction

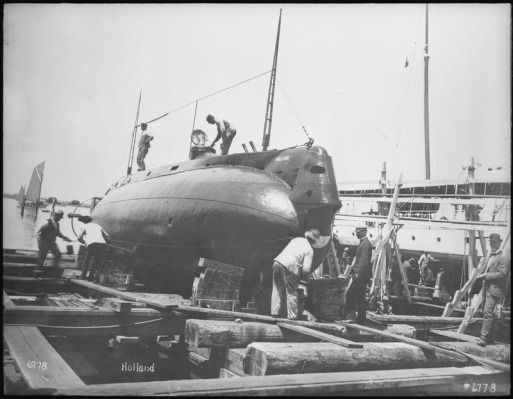

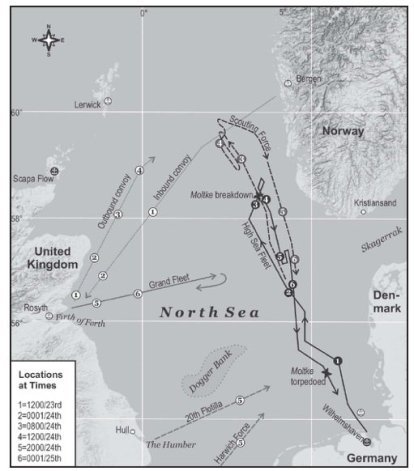

As Marc Milner recently explained in the context of the Second World War, ‘the first line of defense of trade was always the main battle fleet.’[i] What was true in 1939 was true in 1914. Germany’s High Sea Fleet, able to sortie from its protected anchorages only at significant risk, was reduced to relying on its destroyers, submarines, merchant raiders and naval air service to carry on the naval offensive. Britain’s Grand Fleet, although successful at confining the High Sea Fleet to the North Sea, was in turn unable to protect Britain’s far-flung merchant shipping. The two dreadnought fleets of the great naval antagonists were thus mutually immobilized. Flotilla craft, seaplanes and submarines became the primary instruments in the vast battle over oceanic trade. As British Prime Minister David Lloyd George prosaically described the situation, ‘When the last roving German cruiser had been beached in a mangrove swamp in Africa, in order to escape capture, the German Admiralty put more faith in the little swordfish which had already destroyed more enemy ships in a month than the cruiser had succeeded in sinking during the whole of their glorious but short-lived career. When they realized the power of this invention they set about building submarines on a great scale and constructing much larger types.’[ii]

While the Grand Fleet’s 10th Cruiser Squadron carried out the blockade of Germany, slowly strangling the Central Powers’ access to overseas trade, Germany’s U-boats, seaplanes and destroyers from the High Sea Fleet (HSF) and Flanders Flotillas attempted to circumscribe the blockade and attack Britain’s oceanic supply lines. The U-boats, like the Zeppelins and Gothas in the air, were new technological threats against which Britain’s traditional wooden walls provided no protection. To produce strategic effect with the aerial bomber and submarine, however, it was necessary to violate the laws of civilized warfare as they had been agreed upon by the European powers at the Hague conferences of 1899 and 1907.[iii] For the Zeppelins and Gothas this meant bombing British cities from the air without regard for civilian casualties, and for the U-boats at sea this meant violating the rules for prize capture and indiscriminately sinking enemy and neutral merchant shipping without warning.

The new Admiralty building, from N. A. M. Rodger, The Admiralty (1979)

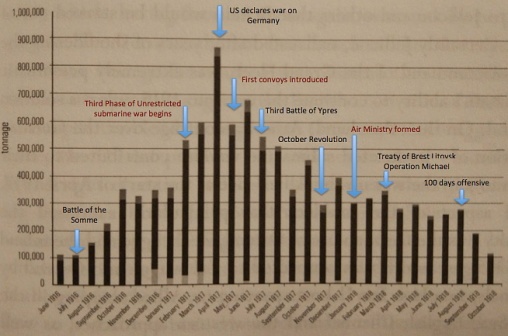

After a trepidatious start in February 1915, when the ‘War Zone’ was established around Britain, by the spring of 1917 the U-boats were well on their way to wiping out Britain’s merchant fleet. During the months of March, April, May, June, July, and August, British shipping losses were always above 350,000 tons, with losses peaking at 550,000 tons in April, and 498,500 tons in June.[iv] The Admiralty, under the leadership of First Sea Lord Sir John Jellicoe and First Lord Edward Carson, had computed the loss rate and expected that, if no solution were found to the submarine crisis, Britain would soon be reduced by starvation and thus forced to abandon the war long before the yearend of 1918.[v]

London, c. early 20th century, by William Wyllie

The Royal Navy undertook a herculean effort to reduce shipping losses and increase Anti-Submarine (A/S) capabilities. Steadily improved counter-measures, reorganization at the Admiralty and in particular of the Naval Staff, and the gradual implementation of escorted convoys during the summer of 1917, began to alleviate the crisis. Although shipping losses remained high, frequently above 200,000 tons per month until the end of the war, this loss rate was not enough to cripple Britain’s supply lines. Furthermore, U-boats were now forced to attack defended convoys, raising the risk of counter-attack and eventually resulting in the development of wolf pack tactics, as were seen a quarter century later during the Second World War.[vi]

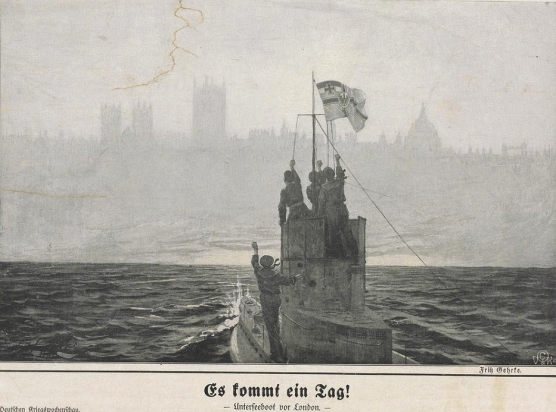

The Eye at the Periscope aboard a Royal Navy submarine, Francis Dodd collection

Although the implementation of escorted convoys curtailed shipping losses, and forced the otherwise ephemeral U-boats to attack prepared warships, the inability of the Royal Navy to attack and destroy the High Sea Fleet meant that any operation aimed at capturing or destroying the U-boat bases themselves, or attempts to mine the U-boat areas of operations, could potentially prompt a fleet action in the enemy’s thoroughly mined waters: raising the prospect of catastrophic losses for the Royal Navy.

Convoy in rough seas, 1918, by John Everett

Later in 1918 the famous ZO operation was conducted in an attempt to block the bases at Zeebrugge and Ostend, while a redoubled aerial bombing campaign was additionally carried out. Finally, in October 1918, with the One Hundred Days offensive systematically rolling back the German army and liberating Belgian,[vii] the Royal Navy commissioned HMS Argus, an aircraft carrier system that included the Sopwith T1 ‘cuckoo’ capable or launching aerial torpedoes and thus opening the prospect for a torpedo strike against the High Sea Fleet in harbour – guaranteeing the defeat of Germany’s main fleet. And without the main fleet to protect the bases, the U-boats, minesweepers and flotilla destroyers carrying out the anti-shipping war would quickly find operations extremely difficult under the guns of Grand Fleet warships.

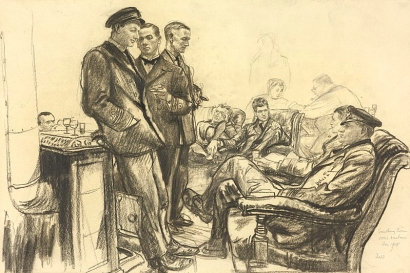

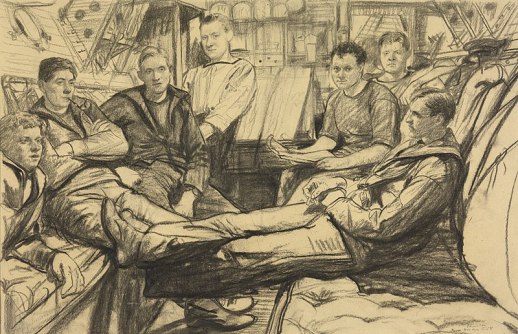

The Smoking Room, HMS Ambrose, Francis Dodd collection

The Smoking Room, HMS Ambrose, Francis Dodd collection

This blog examines the multidomain nature of the unrestricted U-boat campaign of 1917 – 1918, and demonstrates the unpreparedness of the Royal Navy to combat the submarine threat, but also the extensive reforms undertaken that eventually defeated the U-boats. By November 1918 the Royal Navy had devised a comprehensive and effective A/S and trade defence system, to which Germany’s raiders could not respond with any hope of success.

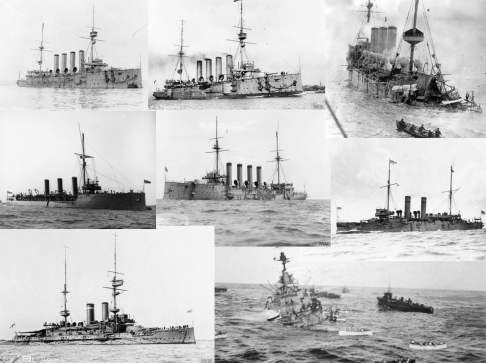

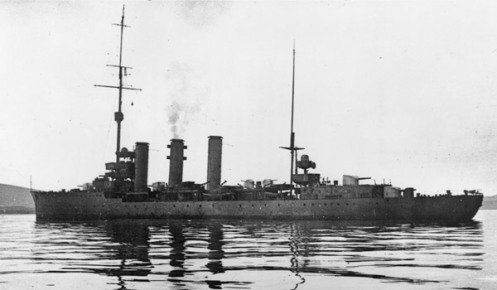

Various British warships sunk by U-boats and mines, 1914 – 1915, three armoured cruisers, three pre-dreadnought battleships, two light cruisers and HMS Audacious a 28,000 ton super dreadnought, completed in 1913, which struck a mine.

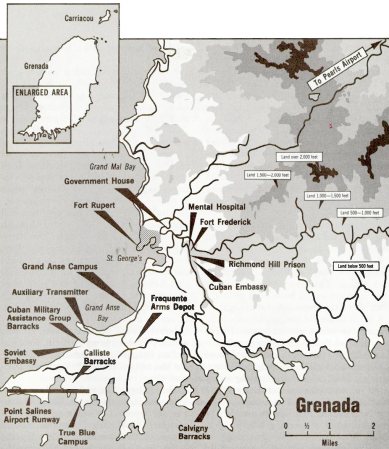

For both the Royal Navy and the Imperial German Navy (Kaiserliche Marine), the First World War began with a flurry of surface and submarine activity. After the demise of Admiral von Spee at the Battle of the Falkland Islands, Admiral Souchen’s arrival in Istanbul, and the Heligoland Bight and Dogger Bank engagements of August 1914 and January 1915, the surface threat, beyond a few isolated light cruisers and merchant raiders, had been broadly curtailed.[viii]

Germany’s U-boats, for their part, destroyed a series of high-profile targets early in the war, from the seaplane carrier HMS Hermes, to the scout cruiser HMS Pathfinder, and the three armoured cruisers: HMS Crecy, Hogue and Aboukir. The new dreadnought HMS Audacious was lost to a mine on 27 October 1914, and the pre-dreadnought battleship HMS Formidable was torpedoed by U24 on New Years Day 1915. To add insult to injury, HMS Majestic and Triumph were both torpedoed at the Dardanelles by U21 during the May crisis of 1915.

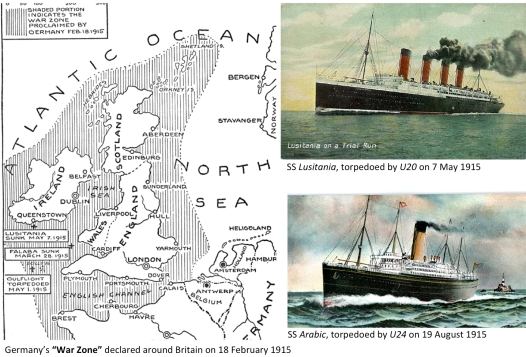

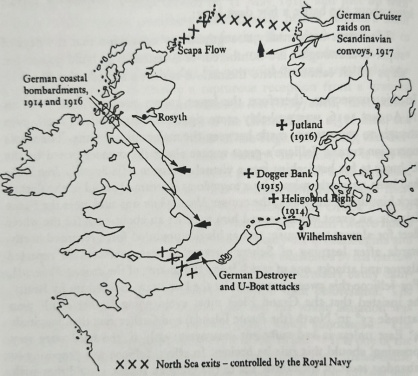

The submarine and mine threat had a significant impact on Britain’s strategic position. The Grand Fleet required not only a protected and submarine-proof anchorage from which to operate, but also a large force of destroyers to escort it while at sea. The submarine’s emergent role as a commerce destroyer caught the Allies off guard. The decision in January 1915 by the Kaiser to authorize the designation of a ‘War Zone’ around Britain, in which British merchant shipping would be destroyed as part of a counter-blockade strategy, seemed a barbaric example of German ‘frightfulness’.

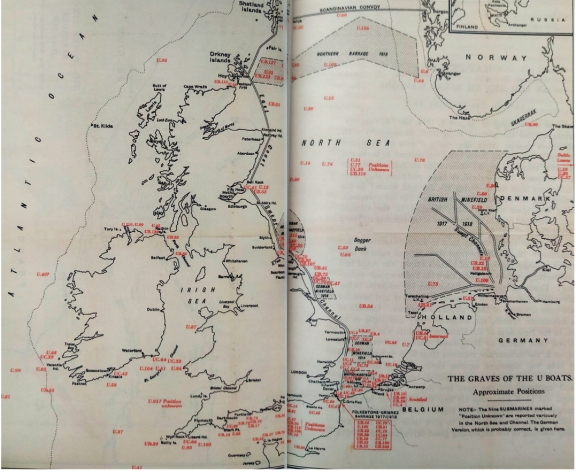

The strategic situation in the North Sea, 1917 – 1918, Map 9 from Paul Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery (1998), p. 248

Although shipping losses increased, Germany’s U-boats were not yet plentiful enough to seriously impact the war, and the embarrassing sinking of the liners Lusitania in May and Arabic in August 1915, both with loss of life for American and other neutral citizens, encouraged the Kaiser to restrain the anti-shipping war. The new doctrine of surface battle, promulgated by Admiral Reinhardt Scheer, necessitated the withdrawal of the U-boats during 1916 to combine with the Navy’s Zeppelins for fleet operations. The singular result of the Battle of Jutland on 31 May, followed by the aborted August sortie, convinced Scheer that the British blockade could not be cracked by the High Sea Fleet.[ix] The new German war leadership under Ludendorff and Hindenburg, as such, made the decision late in 1916 to gamble on the U-boats sinking enough British, Allied and neutral tonnage to cripple Britain’s war effort and thus tip the war in Germany’s favour.

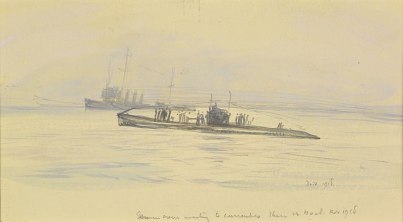

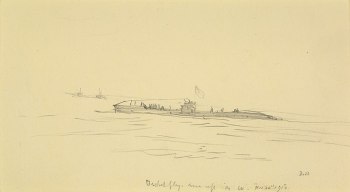

Various Francis Dodd drawings from 1918, done from Royal Navy submarines, trawlers, launches and merchant ships. The machine world successor to its wooden counterpart a century before.

On the Western Front, meanwhile, the Allied offensive in France was to be renewed under Generalissimo Joffre’s replacement, General Neville. This was to be an offensive the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) would support at Arras, and included the plan to capture Vimy Ridge.[x] The Allies, to supply this offensive, required huge quantities of material. The cross-Channel coal trade in particular was crucial for fuelling the French war effort: 800 coal transports crossed the English Channel in November 1916 alone.[xi] Other seaborne trade, such as food, shells, and especially fodder for the BEF’s horses, likewise required transshipment across the Channel by merchant ships. Critical supplies of metal and ore were delivered across the North Sea from Scandinavia, goods and commodities were imported across the Atlantic from America and out of the Mediterranean through the Gibraltar Straits. This cornucopia of merchant shipping was exposed, defenceless, and ready-made prey for the unleashed U-boats.

Merchant shipping tonnage sinking by submarines and other means June 1916 to October 1918, from Duncan Redford and Philip Gove, The Royal Navy, A History Since 1900 (2014)

U-boat Offensive, January – March 1917

From the perspective of the German high command the clear weakness in the Western Allied armies was their exposed seaborne logistics. High Seas Fleet C-in-C Admiral Reinhard Scheer, in his 4 July 1916 report on the Jutland battle to the Kaiser, stated his belief that the only way to defeat Britain would be through economic means, meaning “setting the U-boats against the British trade routes.”[xii]

Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer, Commander-in-Chief of the High Sea Fleet & Admiral Henning von Holtzendorff, Chief of the Admiralty Staff (Admiralstab), photograph by Hanse Hermann, Leipzig, 1918

On 22 December Admiral Holtzendorff accepted this view and advocated, in a fateful paper, for the destruction of all shipping approaching Britain.[xiii] Holtzendorff was convinced that if 600,000 tons of merchant shipping could be sunk each month, and sustained for a period of five months, the British would give in.[xiv] The renewed unrestricted submarine campaign commenced at the Kaiser’s order on 1 February 1917.[xv]

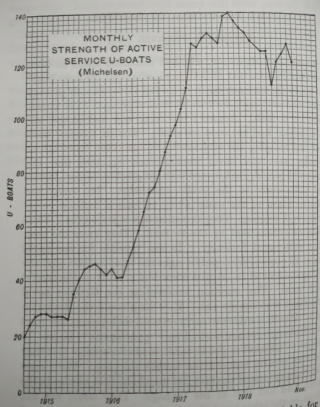

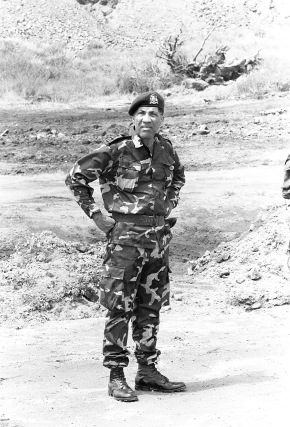

Commodore Andreas Michelsen, author of the book Submarine Warfare, 1914-1918, CO North Sea U-boats, Befehlshaber der Unterseeboote, June 1917 – November 1918. He replaced Fregattenkapitan Hermann Bauer.

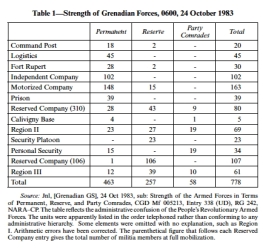

Early in 1917 there were 111 U-boats available, 49 with the HSF at Wilhelmshaven, 33 at Zeebrugge and Ostend, with another 24 at Pola in the Mediterranean, two at Constantinople and three in the Baltic.[xvi] The Flanders Flotilla (coastal) U-boats alone had managed to sink enough shipping to reduce the cross-Channel coal trade by 39% during the final quarter of 1916.[xvii] This was enough of a threat to the French armaments industry that the Royal Navy’s Auxiliary Patrol, on 10 January 1917, commenced escorting large convoys of 45 ships across the Channel, 800 ships every month.[xviii]

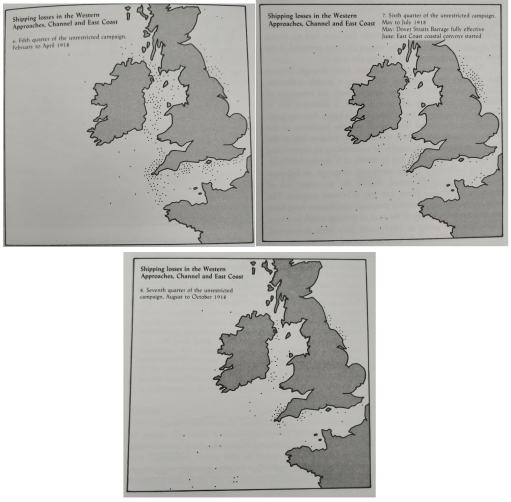

April 1917: the catastrophic increase in Atlantic shipping losses, combined with a spike in Mediterranean losses, seemed to defy all of the Admiralty’s efforts. The potential for disaster seemed overwhelming. By this point, the French coal trade was being escorted across the English Channel, and the Dover barrage was being rebuilt with more effective mines. Despite this, nearly 100,000 tons of shipping had been lost in the Channel by the end of April. From Newbolt, Naval Operations, vol. IV, p. 382-3

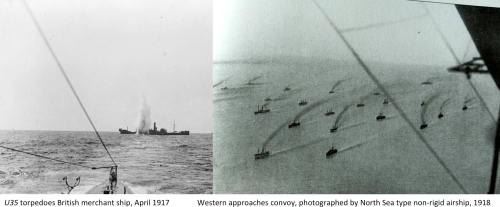

With the restrictions on neutral shipping lifted, the U-boats began the slaughter. 35 merchant ships were sunk in the Channel and Western approaches the first week of February 1917 alone.[xix] By the end of February the U-boats had accounted for half a million tons, making more than a million cumulative when another 560,000 tons were sunk in March. The campaign high point was reached in April when 860,000 tons of Allied, British and neutral ships were destroyed.

Allied shipping losses in Channel and Western Approaches for 1914-15 and 1916

These figures represented the destruction of 1,118 Allied and neutrals in the first four months of 1917: 181 in January, 259 in February, 325 in March and 423 in April.[xx] Between 1 February and the end of April 1917, 781 British merchant ships had been attacked, another 374 torpedoed and sunk, plus 154 sunk specifically by U-boat cannons.[xxi] The United Kingdom exported 122,600,000 tons of goods in January, a value that fell to 93,200,000 in February.[xxii] Only nine U-boats, including accidents, were destroyed between February and April.[xxiii]

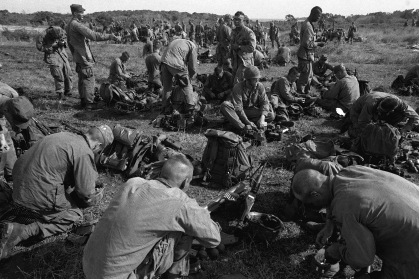

The Imperial War Cabinet, Jellicoe is standing at the back, second from left. First Lord of the Admiralty Edward Carson is third.

In Britain the new parliamentary coalition under former Munitions and then War Minister and now Prime Minister David Lloyd George was faced with an unprecedented crisis. In early December 1916 Admiral Sir John Jellicoe had been promoted out of the Grand Fleet and advanced to First Sea Lord (1SL), with the explicit objective of curtailing the submarine threat.[xxiv] There were many ideas about what to do, and it was not initially clear what the correct response was, and opinion in the Royal Navy was split. Captain Herbert Richmond believed convoy escort to be the obvious solution,[xxv] a subject he had studied in his historical work with Julian Corbett on 18th century naval warfare (published after the war as The Navy In The War of 1739-48).[xxvi] Both historians noted the importance of trade interdiction and convoy protection efforts in the Caribbean, and Corbett added the Korean peninsula experience in his staff history of the Russo-Japanese War.[xxvii]

Old Waterloo Bridge from South Bank by William Wyllie

Traditionally, Britain had indeed managed the threat from corsairs and privateers by convoying its merchant shipping. On 29 December Jellicoe, however, expressed his skepticism that convoy was the appropriate solution to the U-boat problem. The First Sea Lord’s position, in general, was that the historical analogy of convoy protection was no longer valid, given the vast increase in oceanic shipping, the supposed delays in loading, offloading, and assembling the convoys, coupled with limitations on available escorts.[xxviii] The reality was that the First Sea Lord perceived convoys as sitting targets, and was unable to transcend the tactical paradigm whereby the escorted convoy not only “reduced the number of targets” and thus increased the number of successful sailings, but also forced the U-boats to carry out attacks from positions where they would be exposed to destroyer counterattack.[xxix]

Furthermore, the figures the Admiralty estimated would be required for Atlantic merchant convoy escort were excessively high: 81 escorts for the homeward-bound Atlantic trade, and another 44 for the outward-bound trade.[xxx] Since the requirements of the western approaches had been minimized to increase destroyer numbers at Dover, Harwich, Rosyth and Scapa Flow, Jellicoe foresaw a situation in which the battle fleet’s escorts would be precariously reduced to endlessly feed requirement for merchant shipping escorts, as did in fact occur during Admiral Sir David Beatty’s second year as Grand Fleet C-in-C.

Photograph of Admiral Sir John Jellicoe as C-in-C Grand Fleet

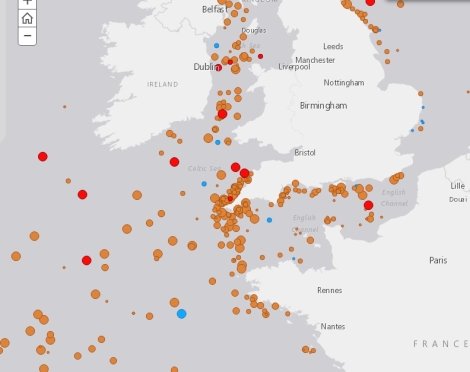

When Jellicoe arrived, and until the April crisis, Britain’s trade defence policy was one of patrolling a series of shipping lanes, combined with aerial patrols over the coasts.[xxxi] The Admiralty had adopted an ‘approach route’ system, by which, rather than using its anti-submarine vessels as convoy escorts (convoys being believed to be large, slow moving, targets), the A/S vessels would patrol various approach ‘cones’ of which there were four, hoping to sweep them clean of enemy submarines.

Approach A: Apex at Falmouth, shipping from South Atlantic and Mediterranean, destined for London, English Channel, and East Coast Ports.

Approach B: Apex at Berehaven, shipping from North and South Atlantic, destined for Bristol Channel, London and English Channel and Mersey.

Approach C: Apex at Inishtrahull, shipping from North Atlantic for Clyde, Belfast, Irish Sea and Liverpool.

Approach D: Apex at Kirkwall, shipping from North Atlantic for North-East ports to the Humber.[xxxii]

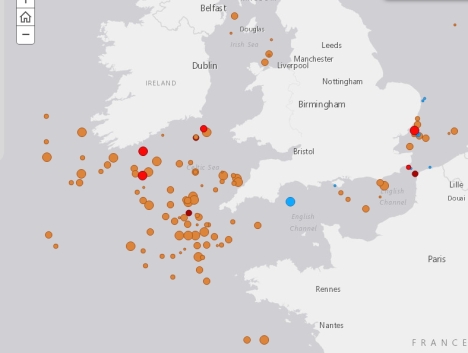

The Admiralty’s initial Western Approaches ‘zone’ scheme, as established at the beginning of 1917, and the corresponding locations of sunk merchant ships. The unescorted approach lanes were ideal prey for the patient U-boat commander.

Allied shipping losses in the Channel and Western Approaches for 1917

In practice this system proved disastrous, effectively funnelling in and outbound shipping into dangerously crowded and exposed lanes. Although the actual lane utilized was random, the need for a great number of destroyers to patrol the approach area still made U-boat contact unlikely and trade defence precarious. The approach-lane program, as Henry Jones put it, had the effect of ‘concentrating great numbers of ships along the patrol routes off the south coast of Ireland and in the Bristol Channel.’[xxxiii]

The Western approaches were at first starved for resources: only 14 destroyers stationed at Devonport for use ‘escorting troopships and vessels carrying specially valuable cargoes through the submarine danger zone,’[xxxiv] in addition to 12 sloops at Queenstown.[xxxv] Jellicoe transferred an additional ten destroyers from Admiral Beatty to the Senior Naval Officer (SNO) Devonport, at least partly with the intention of increasing the number of escorts available for providing escort to troop or munitions ships.[xxxvi] Aircraft and airship bases had not yet been constructed to cover these approaches,[xxxvii] and the Dover Barrage, meant to prevent the Flanders U-boat flotillas from crossing the Channel, proved totally ineffective. Worse, there were only enough depth-charges to equip four per destroyer at the beginning of 1917, and as late as July, only 140 charges were being produced each month. By the end of 1917 this number had increased to 800, sufficient to equip destroyers with 30 to 40 charges.[xxxviii]

Although Jellicoe implemented strong reforms meant to improve all areas of the A/S patrols, from increased depth-charge production, to building new RNAS bases on the coast; the crisis continued to worsen. Shipping losses increased in March and by early April 1917 had reached an apex. The officers responsible for the particularly exposed Scandinavian sea route met at Longshope, in the Orkneys, on 3 April and determined in favour of implementing convoys to protect North Sea sailings.

Motor Launch in the Slipway at Lowestoft, Francis Dodd, April 1918

As we have seen, convoys – or protected sailings – had already been implemented to cover the Channel crossing, and they were far from a novel concept. The War Cabinet secretary, Colonel Maurice Hankey, had in fact prepared a paper for David Lloyd George on the subject of ASW on 11 February 1917.[xxxix] This paper outlined the flaws in the current patrol system and unequivocally advocated the adoption of convoy and escort as the correct solution. Hankey’s observations regarding the benefits of convoys were particularly cogent:

The adoption of the convoy system would appear to offer great opportunities for mutual support by the merchant vessels themselves, apart from the defence provided by their escorts. Instead of meeting one small gun on board one ship the enemy might be under from from, say, ten guns, distributed among twenty ships. Each merchant ship might have depth charges, and explosive charges in addition might be towed between pairs of ships, to be exploded electrically. One or two ships with paravanes might save a line of a dozen ships from the mine danger. Special salvage ships… might accompany the convoy to salve those ships were mined of torpedoed without sinking immediately, and in any event save the crews. Perhaps the best commentary on the convoy [escort] system is that it is invariably adopted by our main fleet, and for our transports.[xl]

Two days later, at an early morning 10 Downing Street meeting, Lloyd George, Carson, Jellicoe and the Director of the Anti-Submarine Division (DASD) of the Naval Staff, Rear Admiral Alexander Duff, spent several hours during breakfast discussing Hankey’s convoy paper. Jellicoe objected on the grounds that the lightly escorted convoys would make vulnerable targets and that merchant captains would not be capable of the complex station keeping required, or indeed zig-zag maneuvering, objections that did not convince Lloyd George, as Hankey described in his diary.[xli]

“The Pool” view of River Thames, by William Wyllie

The following week Jellicoe prepared a War Cabinet paper describing the progress of A/S measures so far taken by the Admiralty.[xlii] Jellicoe’s primary recommendation was merely to reduce the total maritime traffic, notably by abandoning supply for the Salonika front. This was a dismal situation, as Jellicoe put it, ‘the Admiralty can hold out little hope that there will be any reduction in the rate of loss until the number of patrol vessels is largely increased or unless new methods which have been and are in process of being adopted result in the destruction of enemy submarines at a greater rate than that which they are being constructed…’. At this time, Jellicoe illustrated mechanical thinking in his belief that an additional 60 destroyers, 60 sloops, and 240 trawlers would be needed for a patrol scheme of ultimately unspecified final scale, citing the case of the English Channel where auxiliary patrol vessels formed a complete lane through which traffic passed. His third recommendation was the destruction of the submarine bases themselves.[xliii]

The expansion of A/S measures was above all else the priority for Jellicoe as soon as the new Admiralty administration was settled. The new First Sea Lord immediately set about re-organizing the staff and mobilizing naval logistics to supply new bases, improve torpedoes and mines, and create a host of flotilla and auxiliary craft for A/S purposes. DASD Rear Admiral Duff soon recognized the need for aerial patrol over the western approaches. In December 1916 Duff had requested that Director Air Services Rear Admiral Vaughan Lee implement a patrol schemes at Falmouth, the Scillies, Queenstown, Milford Haven, Salcombe, and Berehaven, to cover the exposed approach lanes.[xliv] In February three H12 flying boats were flown out to the Scillies to patrol the Plymouth approach.[xlv]

The U-boats were not alone in their exertion during February. The Kaiserliche Marine’s Zeebrugge force conducted raids against the Dover straits as the U-boats worked up towards maximum effort. The destroyer situation in the Royal Navy at this time was scattered: there were nominally 99 destroyers available with the Grand Fleet, 28 deployed with the Harwich Force, 37 with the Dover Patrol, 11 attached to the Rosyth, Scapa, Cromarty area, 24 at the Humber and Tyne, 8 at the Nore, 32 at Portsmouth, 44 at Devonport and 8 at Queenstown, although this includes ships refitting or being repaired, and not therefore the true operational strength.[xlvi] This great dispersion of force meant it was possible for Germany’s high-speed torpedo boat destroyers to sortie and conduct night raids with good chances of success.

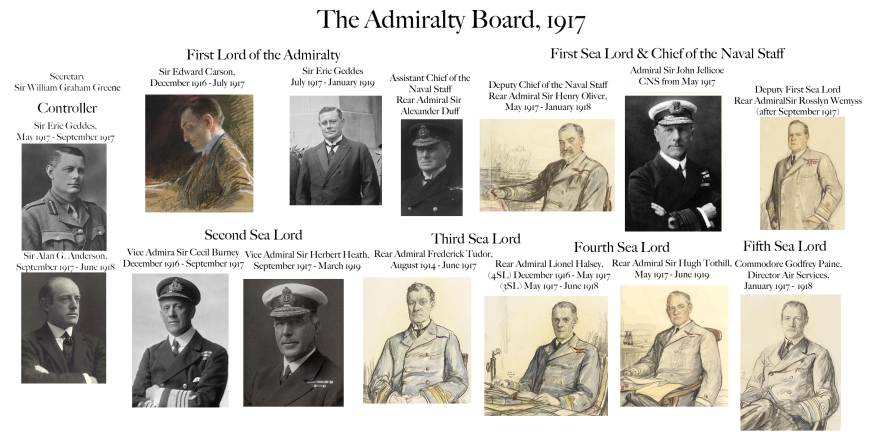

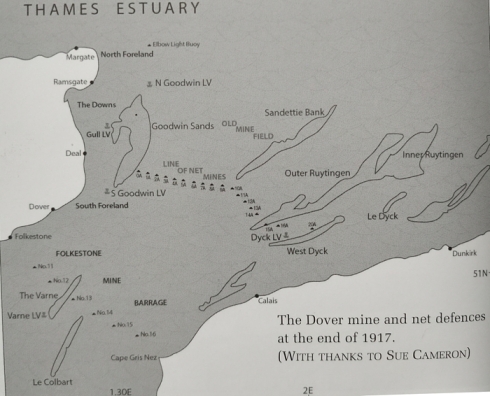

Map showing the simplified Channel Barrage, the main Folkestone – Gris Nez line and the outer Channel explosive mine net at the end of 1917, Dunn, Securing The Narrow Sea (2017)

To test the Channel defences, Admiral Scheer, early on 25 February, ordered the Zeebrugge destroyers to conduct a raid on the Dover coast with three groups, the first comprised of six boats of the First Half-Flotilla (G95, G96, V67, V68 and V47, Lieutenant Commander Albrecht in G95), the second comprised of four boats of the Sixth Flotilla (Lieutenant Commander Tillessen in S49, with V46, V45, G37, V44 and G86), plus a small diversion force of three boats from the Second Half-Flotilla.[xlvii] Albrecht was to target the Downs while Tillessen attacked the Barrage itself. HMS Laverock, a destroyer armed with three 4-inch guns under the command of Lieutenant Henry Binmore, encountered one of the approaching flotillas around 10:30 pm on the 25th.[xlviii]

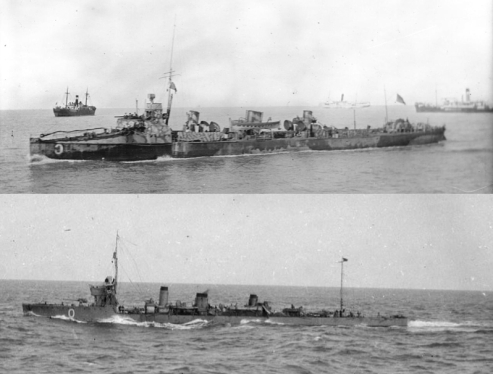

SMS V43, 1913-class torpedo boat destroyer & Representations of Zeebrugge flotilla destroyers, V67 & G37

After a brief encounter the two sides slipped into the darkness, contact was lost and Tillessen turned back to base. The diversion force found no targets near the Maas, while the First Half-Flotilla carried out a brief shore bombardment of North Foreland and Margate, with no military consequence. Admiral von Schroder, in command of the naval and marine forces in Flanders, considered the operation a success in so far as it was a worthwhile distraction, drawing RN assets away from submarine hunting.[xlix]

A second raid on the Dover defences was organized for the night of March 17-18, during which 16 Flanders destroyers sortied under Tillessen’s command. On this occasion, the Dover destroyer HMS Paragon was torpedoed and sank, with the loss of 75 members of the crew, by boats from Germany’s Sixth Flotilla.[l] HMS Llewellyn was badly damaged by a torpedo attack when it came to assist the sinking Paragon.[li] The Second Half-Flotilla, for its part, sank the anchored merchant ship Greypoint and damaged a drifter near Ramsgate, which they also shelled without effect. Another raid on 24 March, this time against Dunkirk, destroyed a another pair of merchant ships.[lii] While these surface raids kept pressure on the Dover Strait defences, the shipping crisis itself was spiralling out of control.

U-boat Crisis, April – June 1917

On Saturday 24 March 1917, the London Times reported on Mr. J. M. Henderson’s parliamentary speech. On Friday the MP from Aberdeenshire stated that, due to the hardships suffered by the poor during the harsh winter of 1916, it would be necessary that ‘the Government should issue regulations under the Defence of the Realm Act directing the local authorities throughout the country to establish depots for the sale and delivery of coal, sugar, and other necessaries.’[liii] The creeping realization amongst the commons that the supply situation was deteriorating was not lost on the Lloyd George government. Indeed, the War Cabinet had already recognized, notably in a series of meetings during the second half of February, that food stockpiling and public rationing were both imperative and imminent.[liv]

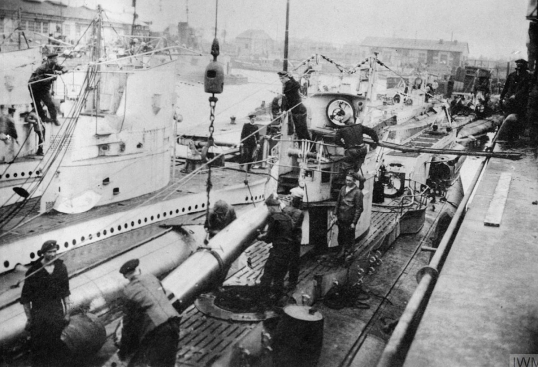

Loading torpedoes aboard a coastal U-boat (UB-type), maintained at the Bruges base, 1917

By 21 March the situation was so serious that Arthur Balfour, then the Foreign Secretary, had been forced to convey to the Netherlands that the UK was likely going to begin requisitioning their shipping.[lv] On 2 April the War Cabinet considered the situation ‘most serious’.[lvi] The desperate nature of the shipping losses, and the inability of the Admiralty to resolve the crisis, can be seen in the War Cabinet’s consideration that smaller merchant ships should be built, thus compelling ‘the enemy to expend as many torpedoes as possible in his submarine campaign.’ It was also considered at the 2 April meeting that compulsory mercantile service may be required due to the potential collapse of crew morale.[lvii] All this chaos was being caused by roughly 50 U-boats, an unsustainably high figure that dropped to 40 in May as a result of the exhausting operational tempo the preceding month.[lviii]

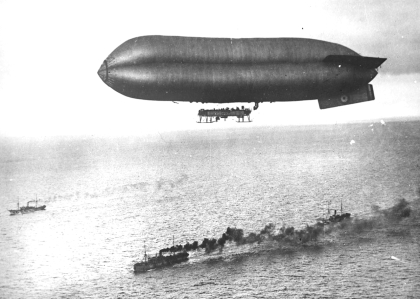

Jellicoe, as First Sea Lord, could imagine only material solutions: strengthening merchant ships with bulkheads, or building enormous 50,000 ton ‘unsinkable’ ships for transporting wheat – further indications of the desperate situation.[lix] Indeed, some of the measures recommended to reduce losses were so desperate that had they been implemented the result would have ultimately had a negative impact on the anti-submarine war, such as the War Cabinet suggestion that the Admiralty reduce construction of airship sheds to save steel (airships proved to be ideal platforms for escorting convoys).[lx]

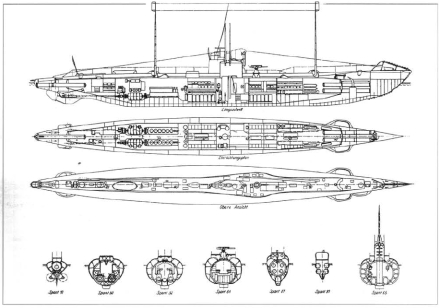

UB III type costal submarine, 500 tons displacement, crewed by three officers and 31 men, armed with four bow and one stern firing torpedoes, plus a single 8.8 or 10.5 cm gun

By 4 April figures provided by Sir Leo Chiozza Money, the Shipping Controller, indicated that by February 1918 merchant shipping tonnage would increase by 850,000 tons from building in Britain, plus 312,000 tons abroad, to which could be added the 720,000 tons of German shipping then seized in American ports. At this time it was believed that this new construction, combined with other efficiencies, would be enough to see the United Kingdom through only until the end of the year.[lxi]

On 1 January 1917 the British Empire possessed 16,788,000 tons (gross) of shipping. By 1 May this figure had fallen to 15,467,000 tons, despite new construction.[lxii] At the height of the crisis in April it was expected that the total would likely fall to around 12,862,000 by the end of the year, in other words, that 3.9 million tons would be erased during 1917. In fact, a staggering 9,964,500 tons were destroyed, globally, during the year, of which 3,729,000 had been British, almost matching the Admiralty estimate in April 1917.

The British Army needed to import 428,000 tons a month. The Ministry of Munitions imported another 1,400,000 tons monthly. For comparison, Britain imported one million tons of cotton, 70,000 tons of tobacco and 400,000 tons of fertilizers on a monthly basis. It was believed that a minimum of 553,000 tons of goods were required every month to sustain the civilian population.[lxiii] According to Jellicoe’s calculations, 8,050,000 tons of shipping were required for the Navy and Army, and on 1 January 1917 there were 8,394,000 tons available for vital imports. By 31 December 1917 the latter figure would therefore have been reduced to 4,812,000 tons, or a loss of 2.78 million tons of civilian imports per month.[lxiv]

The degree of the crisis is told by these statistics, implying a monthly loss rate of between 300,000 and 500,000 tons for the remainder of 1917. The final, and potentially decisive, result was that civilian imports would fall from three million tons in January to 1.6 million tons by the end of the year. Certainly strong economy would be necessitated, in addition to rationing that if continued unchecked would result in the extinguishing of non-military trade by the summer of 1918.[lxv]

Top scoring U-boat ‘aces’ based on proven tonnage destroyed, from Michelsen, Submarine Warfare, p. 218

While the debate carried on at the Admiralty and in the War Cabinet, the district commanders and SNOs were beginning, on their own accord, to form proto-regional commands and implement convoys. As we have seen, the Scandinavian mineral trade and the Channel food and coal trade. had both been placed under convoy with good results.

Some relief occurred on 3 April when the United States joined the war, a momentous event that was welcomed by the War Cabinet three days later. Diplomatic efforts were crucial if the American and Allied war efforts were to be united for maximum impact. Balfour therefore traveled to the United States aboard RMS Olympic while Rear Admiral William Sims, USN, crossed over to Britain in exchange.[lxvi] When Sims, who had traveled across the Atlantic in civilian disguise – in fact, aboard a merchant ship that struck a mine during the voyage – arrived in London and met with Jellicoe, the message Jellicoe had to convey, as Prendergast and Gibson put it, was dire: ‘the German submarines were winning the war.’[lxvii] On Monday, 9 April, Jellicoe reported to the War Cabinet that Admiral Sims would make the utmost efforts to mobilize American support for the anti-submarine campaign.[lxviii]

US Ninth Battleship Division, showing USS New York & USS Texas off Rosyth by William Wyllie.

Close coordination with the Americans brought immediate returns as it would now be possible for American imports to Britain to be carried in American merchant ships, freeing British vessels for other duties.[lxix] Auxiliary ships in the form of the 10th Cruiser Squadron (25 armed merchant cruisers and 18 armed trawlers), that patrolled the Shetlands and Faeroes line intercepting American contraband, was no longer required and its ships were redirected to more fruitful purposes until the squadron itself was abolished on 29 November 1917, shortly prior to the arrival in European waters of the United States Navy’s Battleship Division Nine under Rear Admiral Hugh Rodman.[lxx]

Francis Dodd artwork from 1918 showing RN submarine L2 engaging aircraft with its deck cannon.

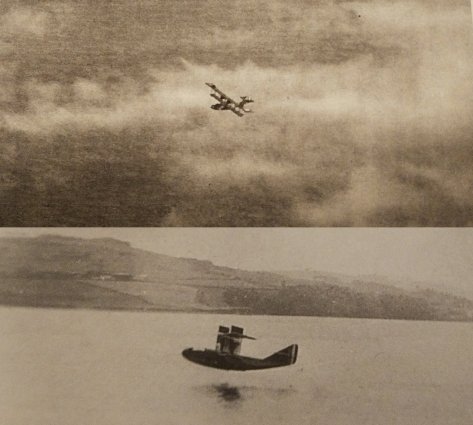

As part of Jellicoe’s material strategy, Royal Navy aircraft were expanded alongside A/S flotilla craft. Flying boats stationed at Yarmouth and Felixstowe were equipped to locate and attack submarines, making possible large-scale A/S patrols supported by surface vessels. As the patrol system evolved the U-boats adjusted their tactics.

By March 1917 Jellicoe could inform Beatty that the Staff believed between 11 and 21 U-boats had been destroyed so far that year.[lxxi] Three German torpedo boat flotillas, between 30 and 40 destroyers were deployed to support U-boat operations.[lxxii] German seaplanes were engaged in a significant battle with the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) for control of the North Sea, as well as carrying out anti-shipping missions, occasionally with success. April was a particularly busy month for the east coast air stations, the Felixstowe H12 flying boats being assigned to conduct ‘spider web’ patrols off the Kentish coast.

H-12 type Felixstowe flying boats on patrol, from Theodore Douglas Hallam, The Spider Web (2009) & ‘Spider Web’ style octagonal patrol areas for NAS Felixstowe.

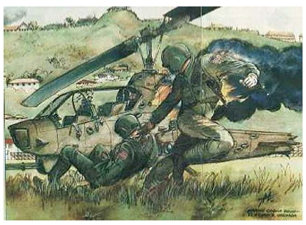

In fact, the situation at Dover, since the raids in February and March, had resolved into an intense destroyer and seaplane conflict in its own right. The War Cabinet was informed on 26 March that 30 German destroyers had been massed at Zeebrugge.[lxxiii] Another destroyer raid was shortly organized, taking place on 20 April. The Fifth Half-Flotilla (V71, V73, V81, S53, G85 and G42) under Korvettenkapitan Gautier was to conduct an attack against Dover, while boats from the Sixth and First Half-Flotilla (Commander Albrecht in V47, with G95, V68, G96, G91 and V70) raided Calais.[lxxiv] Although in the event little damage was caused, the raid alerted Dover forces which sortied to intercept the retiring German destroyers. About 12:45 am the 21st, HMS Swift, commanded by Commander Ambrose Peck, with HMS Broke in support, spotted an unknown torpedo boat to the port bow. Swift attacked the boat, torpedoing G85 and disabling it, while Broke, under Commander Edward ‘Teddy’ Evans, rammed G42 and disabled the torpedo boat in hand-to-hand action.[lxxv] Broke was damaged by S53’s 105 mm cannon, but still managed to sink G85 with a torpedo after the German flotilla retreated. 89 sailors were recovered from G42 and G85.[lxxvi]

HMS Broke, from Steve Dunn, Securing The Narrow Sea (2017)

HMS Broke, from Steve Dunn, Securing The Narrow Sea (2017)

The temporary defeat of the Flanders raiders, the introduction of the Felixstowe flying boats, and above all else, the introduction of the United States, made a powerful tonic for the Admiralty’s ailing morale. Jellicoe, however, still faced a mounting crisis. He turned to the Naval Staff for answers.

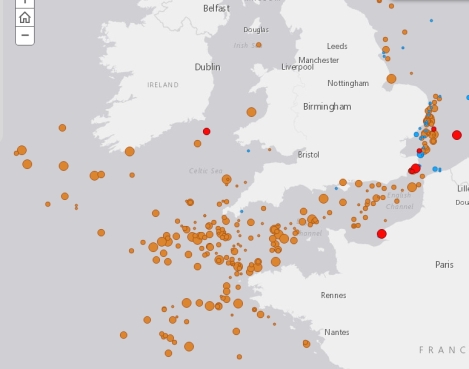

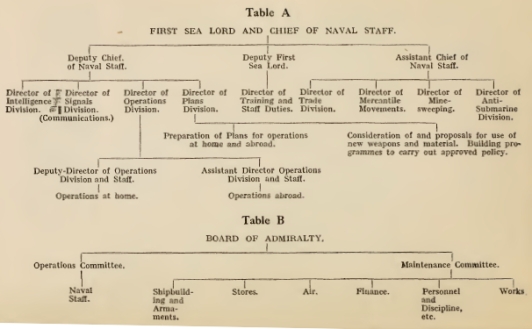

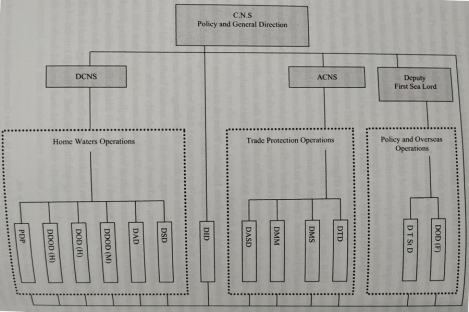

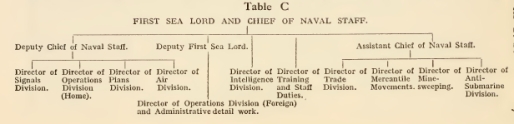

Organization of the Naval Staff, 1905 – 1917 (May), from Nicholas Black, The British Naval Staff In The First World War (2011)

In April 1917 the Anti-Submarine Division (ASD) of the staff was composed of 15 officers and two civilians, spread across seven offices located in the Admiralty Building, Block III.[lxxvii] The U-boat threat plot was kept in a Chart Room within the Convoy Section of the Naval Staff. The Chart Room was managed by Commander J. W. Carrington.[lxxviii] this room, known as the ‘X’ room, displayed a 6’ by 9’ map of all of the known information on submarines, convoys and their most recent locations or sightings.[lxxix] The ASD thus controlled a centralized hub for collecting from the Intelligence Division and disseminating to the Operations Division, U-boat data on the approaching Atlantic convoys. U-boat signal intercepts detected by the Direction Finding (D/F) stations along the coast alerted the Director of Intelligence to submarine activity. The cryptanalysts in Room 40 could then triangulate the location of a transmitting U-boat to within 50 or 20 miles and send this information, via pneumatic tube, instantly to the Chart Room.[lxxx]

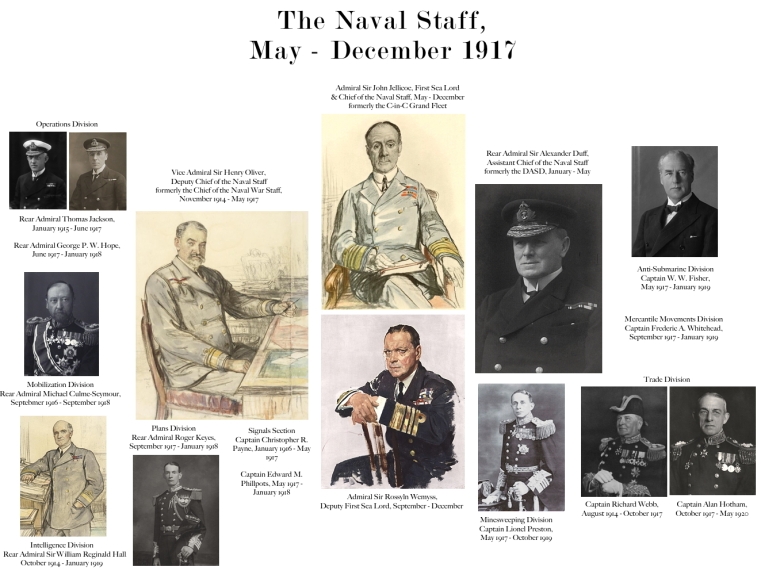

It was imperative that Jellicoe be in the closest touch with the Staff, and in May 1917 he was promoted to Chief of the Naval Staff, uniting that position with the office of the First Sea Lord.[lxxxi] These reforms resulted in Admiral Duff’s promotion to Assistant Chief of the Staff, with Henry Oliver becoming the Deputy Chief.[lxxxii] By assigning duties to the assistant and deputy the Chief of Staff was, in Winston Churchill’s words, relieved of ‘a mass of work.’[lxxxiii] The Director of Operations, Captain Thomas Jackson and, after June 1917, Captain George W. Hope, were to prepare a weekly appraisals of the naval situation, with specific attention to submarines, for the First Sea Lord and the War Cabinet.[lxxxiv]

Organization of the Naval Staff and Admiralty Board, c. September 1917, from Jellicoe, Crisis of the Naval War (1920), p. 20

Captain William Fisher, playing a part in Jellicoe’s reforms, replaced Admiral Duff as DASD. Fisher took a direct interest in operational aspects, orchestrating Jellicoe’s broader mission to centralize methods and material; he would communicate directly with the district commanders, such as on 21 July when he wrote a letter to Plymouth commander Admiral Bethell, proposing the use of kite balloons as a screen for convoys in his Area of Responsibility (AOR).[lxxxv]

The Decision for Convoys

The First Sea Lord, as we have seen, was initially skeptical of the possibilities of convoys.[lxxxvi] Early interest in convoy formation, not only in the English Channel and across the North Sea, but also in the Mediterranean, was ignored.[lxxxvii] Jellicoe’s initial blindness to convoy adoption hinged primarily on the scale of the endeavour. As he pointed out in 1934, the convoy system as had evolved by November 1917 for the Atlantic and English Channel required 170 escort vessels of all kinds (of which, 37 were USN destroyers), plus another 32 escorts covering the northern crossing with Norway, and a another 30 escorts in the Mediterranean for a total of 232 vessels, with another 217 escorts working with the fleet units.[lxxxviii] In practice, assembling, directing and communicating with the convoys proved a strenuous task, atmospheric conditions, enemy jamming, battle damage to communications equipment, all had an impact on a convoy’s, or squadron’s, ability to communicate. An officer was assigned to each arrival/departure terminus to manage assembly and coordinate with the escorts and merchantmen. In any given convoy the convoy itself was under the command of the convoy Commodore, while supporting warships were under the authority of the Senior Officer, Escort.[lxxxix]

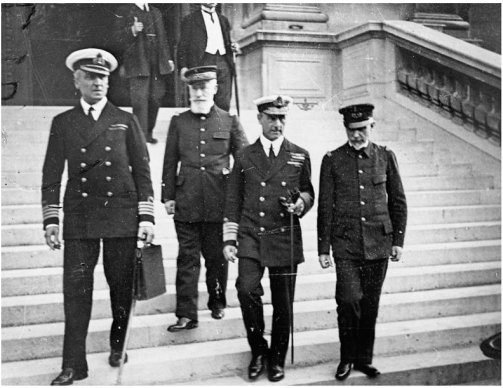

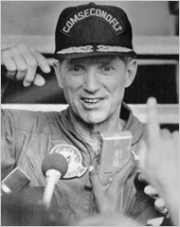

Jellicoe as First Sea Lord, attending the Inter-Allied Conference in Paris, 27 July 1917, Rear Admiral Alexander Duff, the Director of the Anti-Submarine Division of the Naval Staff to his right

In early April the Scandinavian trade began to be convoyed, and with success. This was done at the insistence of the Norwegian government, who urged that the Admiralty do more to protect Norwegian merchant ships in the North Sea, of which 27 were sunk during March, and another 27 in April, plus six Danish and two Swedish neutrals.[xc] Of these ships, as Steve Dunn observes, nine were torpedoed by a single U-boat, U30, over the period 10 to 15 April.[xci] Losses in the Lerwick – Bergan route, between the Shetland Islands and the Norwegian coast, were running at 25% per month since inception.

Although cross-Channel trade was by now routinely convoyed, the scale of crossing the North Sea, and the importance of the trade, including vitals such as ‘nitrates, carbide, timber, iron and steel,’ now necessitated new tactics.[xcii] Vice Admiral Frederick Brock, in command of the Orkneys and Shetlands, and on his own authority, was sharing destroyers for escort work with the C-in-C East Coast of England, and the C-in-C Rosyth: a plan they initiated on 3 March.[xciii]

Greenwich and the Thames, by William Wyllie

Jellicoe could see that this was the best option, given the dismal results from all other efforts.[xciv] Still, the First Sea Lord was wary about depleting the Grand Fleet’s destroyer flotillas, and was skeptical the convoy system would succeed in the long run.[xcv] In April, however, with the success of the Channel coal trade, where ‘controlled sailings’ had been implemented since 10 February with correspondingly dramatic reduction in losses such that, between then and the end of August, only 16 of the 8,871 ships convoyed across the Channel had been sunk.[xcvi] Jellicoe was just beginning to come around to the implementation of Admiral Duff’s comprehensive recommendation for convoying ‘all vessels – British, Allied and Neutral – bound from North and South Atlantic to United Kingdom’.[xcvii]

The pivot, from the perspective of the War Cabinet, occurred on Monday 23 April, when Lloyd George decided upon an upcoming visit to the Admiralty. The PM’s objective was certainly to put pressure on the Admiralty, but also simply to discover the details of whatever trade protection schemes the Navy was working on. Jellicoe had so far not suggested arranging convoys as the solution, rather relying on a multitude of measures, some more effective than others. In this case, DASD Rear Admiral Duff was in agreement with Grand Fleet C-in-C Admiral Sir David Beatty, as well as Admiral Sims, that convoy should be universally adopted. Jellicoe was still skeptical, having been convinced, in the weeks following the 13 February debate with Hankey, by interviews with a number of merchant ship captains who testified that station-keeping and convoy assembling, in particular, of inbound traffic, would be exceedingly difficult if not impossible.[xcviii] Jellicoe also clung to the dearth of destroyers, as well as an apparently deficient convoy trial that Beatty had conducted as counter-arguments. Under pressure from the PM, however, Jellicoe stated that he would reconsider Duff’s convoy proposal.[xcix]

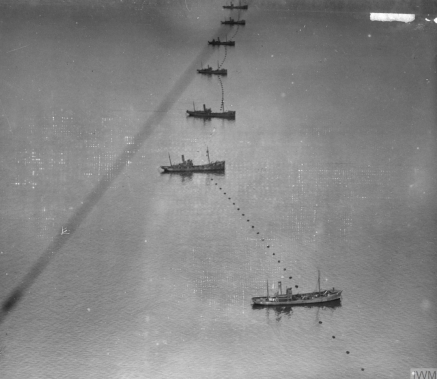

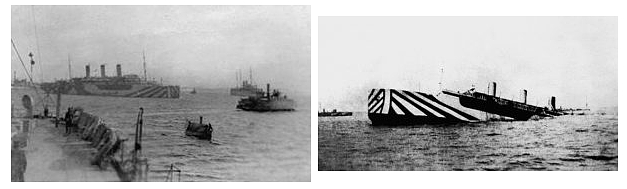

Merchant convoy maneuvering with air support

Duff produced his report three days later, suggesting a program for convoying all Atlantic trade. The DASD observed that, in fact, contrary to Jellicoe’s perspective that convoys were merely larger targets, ‘it would appear that the larger the convoy passing through any given danger zone, provided it is moderately protected, the less the loss to the Merchant Services; that is, for instance, were it feasible to escort the entire volume of trade which normally enters the United Kingdom per diem in one large group, the submarine as now working would be limited to one attack, which, with a Destroyer escort, would result in negligible losses compared with those new being experienced.’[c] Jellicoe approved the scheme the next day, 27 April 1917, that is, three days before the PM arrived at the Admiralty.[ci]

Under Duff’s scheme, the Atlantic trade would be assembled into convoys at four key depots, where they would be joined by escorts and then shuttled into British harbours. Every four days 18 vessels would depart Gibraltar, escorted by two vessels outward and inward bound (requiring six escorts altogether – the other two being spares). Every five days 18 merchants would depart Dakar, protected by three escorts out and in, (nine escorts total). Every three days between 16-20 vessels would leave Louisburg, escorted by four destroyers both ways (12 total), and lastly, every three days 18 ships would depart Newport News, to be escorted by six destroyers (18 total), for a total program of 45 escorts. A further 45 destroyers would provide protection for the final leg of the inbound convoys, with six destroyers meeting each incoming convoy and escorting it to one of the pre-arranged collection points, either St. Mary’s, the Scillies, Plymouth, Milford Haven or Brest.[cii]

130 ton armed lighter X222, one of the armada of light vessels constructed or converted during PM Asquith’s wartime ministries. Originally designed for amphibious landings, these support craft were in converted to A/S patrol and convoy escort duties in 1917

Lloyd George and Hankey did indeed visit the Admiralty on 30 April, and had lunch with Carson, Jellicoe and his family, plus Duff, Captain Webb of the Trade Division and several Assistant Directors from the Naval Staff.[ciii] Jellicoe, the pessimist, considered the Prime Minister ‘a hopeless optimist’ who could not be swayed from his opinions regardless of the 1SL’s cold calculations.[civ] As Hankey phrased it, the meeting ‘set the seal on the decision to adopt the convoy system’.[cv] As significant as the decision in favour of convoys had been, another important decision was made at the next War Cabinet meeting: Lloyd George and Jellicoe agreed that Eric Geddes should be appointed as a civilian naval controller to administer all shipbuilding and supply for naval purposes.[cvi] Geddes strong hand ensured the delivering of the mass of material needed for ASW, with vessels available for A/S duty ballooning from 64 destroyers, 11 sloops and 16 P-boats in July 1917 to 102 destroyers, 24 sloops and 44 P-boats by November, a standard that was maintained well into 1918 when in April there were 115 destroyers, 35 sloops and 45 P-boats available for ASW.[cvii]

It was still early in May when in Washington meanwhile, Sims and Balfour had convinced the Americans to supply 36 destroyers for RN use, a welcome development that would fill half of Jellicoe’s destroyer requirements.[cviii] Indeed, on the 22nd Jellicoe reported to the War Cabinet that the general situation was, ‘for the moment, more reassuring.’[cix] During May the loss rate fell significantly: 106,000 tons of shipping had been destroyed in the Mediterranean, with another 213,000 tons – 78 British ships – lost in all other theatres.[cx]

Furthermore, the RN and RNAS were conducting more frequent engagements with U-boats, suggesting that the A/S measures were having some impact, although as yet there were few concrete results. Of the seven U-boats destroyed during May, only three were attributable to RN efforts: U81, torpedoed by RN submarine E54, UC26, rammed by the destroyer HMS Milne, and UB39 which blew up on Dover Strait mines.[cxi] Significantly, the nature of the U-boat attacks had changed. In March, only 69 ships approaching Britain from the North or South Atlantic had been attacked, with only 32 ships attacked leaving British ports for the same destinations (this was in addition to 62 fishing vessels that were attacked, and another 60 ships in the Channel). By May the figure for import ships attacked had climbed to 100, while the export number had fallen to 20 (only 38 vessels in the Channel attacked, and only 20 fishing vessels).[cxii] Whereas 100,333 tons had been sunk in the Channel during May, only 32,000 tons were sunk in June 1917, a major success.[cxiii]

HMS Fawn, a 380 ton destroyer armed with one 12 pdr and five 6 pdr guns plus two torpedo tubes, on convoy escort duty & a Japanese destroyer escorting the Alexandria – Tarento convoy, 1918

By the end of May 1917, as Henry Newbolt observed, it was the unescorted import trade that was now at the greatest risk of attack: ‘five times as vulnerable as the export trade’.[cxiv] Experimental Atlantic convoys were tested late in May and, by the end of July 1917, 21 Atlantic convoys had run successfully. Of the 354 ships escorted across that ocean, a mere two were sunk by U-boats. Of all convoys run during this period, of 8,894 ships convoyed, only 27 were destroyed by enemy submarines. The statistics demonstrated that convoys were the best method for protecting merchant shipping. Although ships traveling in convoys were relatively safe, there was still a great mass of unescorted traffic that was easy prey for the U-boats. During the May to July period, 910,133 tons of the total 1,868,555 tons sunk was destroyed by High Sea Fleet U-boats operating in the Atlantic.[cxv]

U-boats operating in 1917, and British tonnage sunk per submarine. Newbolt, Naval Operations, vol. V, 1931, p. 195

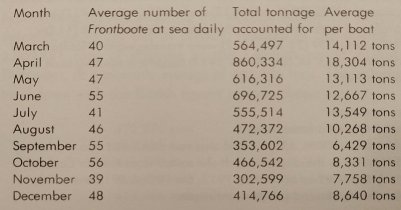

Shipping losses were heavy and Jellicoe reported that, up to 20 May, 185 ships had been sunk by U-boats (105 British, 36 Allied and 44 neutrals), for 239,816 tons of British shipping lost: a cumulative total of 362,183 tons destroyed.[cxvi] Jellicoe estimated this number would likely climb to 500,000 tons before the end of the month. In the event, 616,316 tons (or 596,629)[cxvii] were indeed sunk by the end of May, 352,596 tons of which were British.[cxviii] There were 126 U-boats in Germany’s possession that May, with 47 the average number at sea on a daily basis that month. A month later the figure was 55, falling to 41 in July. 15 boats were lost during that three-month period, equating to 53 merchants ships (124,750 tons) sunk on average for each U-boat lost, which was down from the rate of 86 ships (194,524 tons) during the previous period, February to April.

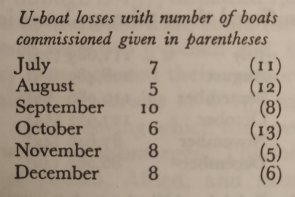

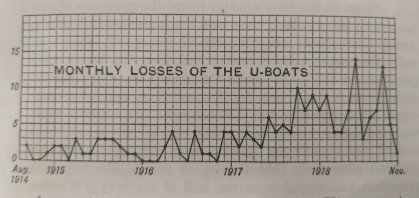

In terms of U-boats lost or destroyed versus new commissions, September was the costliest month for the German submarine force. From Marder, FDSF, IV, p. 278

Unfortunately for the Allies, U-boat losses were more than made up for by the 24 new U-boats constructed during May and July.[cxix] In James Goldrick’s phrase ‘the navy admitted reality’ as more U-boats were urgently required, and an order for 95 boats, mainly UB and UC types but including ten U-cruisers, was placed in early June. At the peak of new construction, after another 220 boats were ordered in June 1918, some 300 U-boats of varying types were on order, 74 were completed in the ten months before the armistice, 1.85 per week.[cxx] Besides the battlecruiser SMS Hindenburg, and three further light cruisers, these would be amongst the last warships completed for the Kaiserliche Marine.[cxxi]

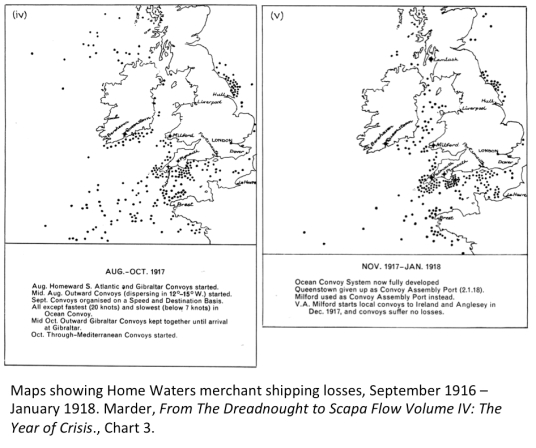

Convoy Implementation, July to September 1917

The improvements in air support, war material, American destroyers, the rolling adoption of convoys, combined with fatigue amongst the U-boats and loss of some experienced crews, was having an impact on the spiralling shipping loss rate. Import trade, which was now generally convoyed, was well protected so once again the U-boats concentrated their efforts against outbound shipping, which so far had not been incorporated into the convoy system.[cxxii] Jellicoe was now convinced of the need to implement a total convoy system, and outward-bound ships began to be convoyed on 13 August, the needed escorts being removed from the Grand Fleet. The results were excellent: during August, only three of the 200 ships convoyed in outbound convoys were lost, a figure that increased to 789 ships convoyed with only two losses during September. Likewise, 1,306 ships were convoyed inbound across the Atlantic, with only 18 lost that month.[cxxiii]

When the system was fully operational, as Arthur Marder described, there were ‘on the average, sixteen homeward convoys at sea, of which three were in the Home Submarine Danger Zone (Western Approaches, Irish Sea, of English Channel), under destroyer escort. There was an average of seven outward convoys at sea, of which four to five were in the Home Danger Zone. It is worth emphasizing that the convoy system protected neutral as well as British and Allied shipping’.[cxxiv]

The effectiveness of the U-boats had been crippled by this comprehensive convoy system, although the Mediterranean, where convoys had not yet been implemented, remained fertile hunting grounds, albeit with too few submarines operating there to represent a serious impediment to Allied supplies. Regardless, between October and November 1917 a convoy system was arranged for those waters, and by the end of November 381 ships, or 40% of all the Mediterranean traffic, had been successfully convoyed with the loss of only nine vessels.[cxxv]

Depth charge attack, by William Wyllie.

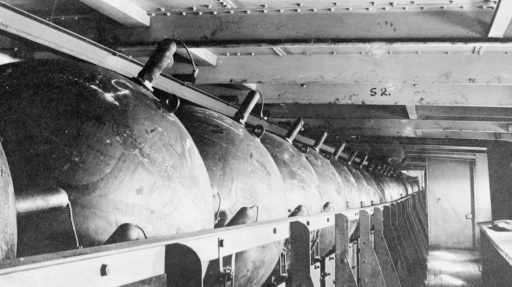

One of the key material improvements was in the quality and quantity of Britain’s undersea weapons, from torpedoes to depth charges and mines. During 1915 and 1916, 6,177 not very effective mines were laid in the Heligoland Bight. In 1917 the Allies reverse-engineered the more effective German mine, and production numbers increased significantly. Jellicoe was an aggressive advocate of mine operations and he championed the introduction of the German ‘horned’ type over the defective British ‘lever’ mines, specifically for the Dover Barrage,[cxxvi] while also advancing the technical and quantitative refinement of aerial bombs and escort depth-charges.[cxxvii] 12,450 mines were produced between October and December 1917,[cxxviii] with 10,389 laid in the Heligoland Bight and Dover Strait. Marder states that 20,000 mines were laid in the Dover Strait and Bight between July and December 1917, of which 15,686 were laid (in 76 fields) in the Bight during 1917.

‘Horned’ mines carried aboard a minelayer.

British mine counter-measures also improved, with 726 vessels counted in the sweeping force, or paravane equipped, so that only ten British vessels, less than 20,000 tons, were sunk by mines during 1918, compared to more than 250,000 tons lost in the first ten months of 1917.[cxxix]

Six U-boats were in fact destroyed by mines between September and the end of the year.[cxxx] At the beginning of 1918 the increased lethality of the Dover, Bight and Zeebrugge minefields meant that U-boats wishing to reach the Atlantic approaches had to exit the North Sea via the Orkney’s passage, or risk running the Channel nets and minefields. A vast effort was decided upon to mine the North Sea exit (250 miles, requiring 100,000 special ‘antenna’ mines),[cxxxi] and plans were examined to block the U-boats’ bases at Zeebrugge, Ostend, and Kiel. Another 7,500 mines would cut-off the Danish strait.[cxxxii]

A scheme to deploy 21,000 mines from Wangeroog to Heligoland to Pellworm, thus attempting to block the base of operations for the High Sea Fleet’s U-boats, was also considered. Actually executing these plans once again raised problems exposed by the schemes of Winston Churchill (Borkum) and Sir John Fisher (Baltic), that had not been resolved in 1914-15. The operation would require a vast armament, success was not guaranteed, and the potential for a catastrophic defeat was real.[cxxxiii]

RNAS Million based Coastal airship C23A escorting a convoy early in 1918 (C23A was wrecked on 10 May near Newbury)

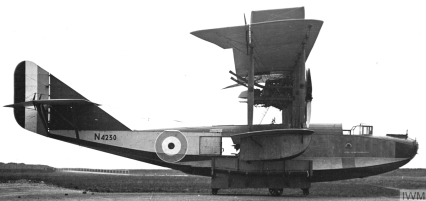

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) had not been neglected in this vast expansion of military hardware. Indeed, the coastal patrol and convoy escort roles supplied by the naval aviators were essential and had been significantly expanded, with 324 seaplanes, flying boats, and airplanes on duty, plus around 100 airships of various types.[cxxxiv]

Felixstowe F3, N4230, IWM photograph.

During 1917 the majority of these aircraft were involved in air patrol missions, in June 1917 only 46 airplane and 46 airship convoy escort missions were flown, but the figure rose to 92 and 86 respectively in September before poor weather curtailed flying.[cxxxv] By April 1918 the figure was 176 and 184, jumping to 402 and 269 in May. Airships provided the convoy with a constant deterrent to submarine attack, except during night, while flying boats and airplanes could fly in advance of the convoy on look-out, or counter-attack any located U-boats with bombs, which increased in potency from 230 lb delayed-fuse bombs introduced in May 1917 to the 520 lb bombs in use by 1918.[cxxxvi]

RNAS and RAF coverage of the Atlantic approaches by the SNO Plymouth and Queenstown. The RNAS South West Group under Wing Captain E. L. Gerrard implemented sweeping ‘spider-web’ flying-boat patrols off the coast of England and Wales, while Vice Admiral Bayly at Queenstown worked with Captain Hutch Cone, United States Navy, to develop flying-boat bases in Ireland.

Although convoy escort and improved A/S methods and material reduced the potential for a starvation defeat, shortages were still a serious problem. Oil imports to the UK were falling drastically as tankers were destroyed. On 11 June Jellicoe reported that he intended to form weekly oil convoys to relieve the situation.[cxxxvii] Two days later Jellicoe reported to the War Cabinet that the implementation of the convoy system was ‘nearly complete.’[cxxxviii]

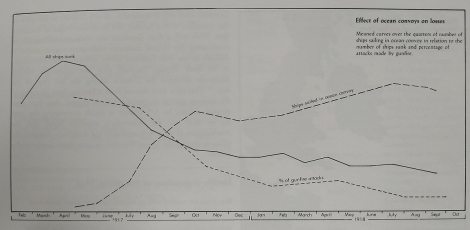

Effects of Ocean Convoys, with the losses vs successful convoy sailing ‘cross-over’ point at August – September 1917, from Tarrant, The U-Boat Offensive, p. 73

Effects of Ocean Convoys, with the losses vs successful convoy sailing ‘cross-over’ point at August – September 1917, from Tarrant, The U-Boat Offensive, p. 73

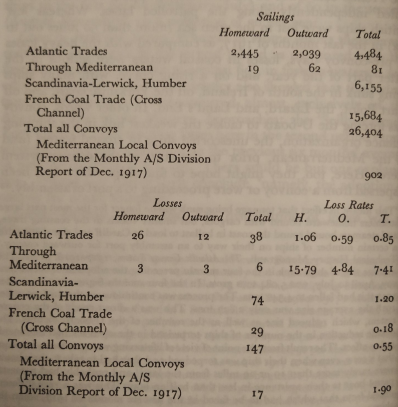

By the end of 1917 26,404 ships had sailed in organized merchant convoys: 4,484 across the Atlantic, 6,155 between Scotland and Scandinavia, and 15,684 in the French coal trade, with a total loss of only 147 vessels.[cxxxix] 32.5% and 42.5%, respectively, of those ships that were lost while being convoyed, were sunk while entering or leaving a convoy, when confusion was at its greatest.[cxl] These results were significant, as compared with June 1917 when 122 British merchant ships were sunk with a loss of 417,925 tons in a single month. Although loss rates dropped significantly by November, 85 ships were still lost to mines (8) and U-boats (76) at loss of 253,087 tons of British merchant shipping in December.[cxli] Allied tonnage losses, that is, non-British shipping losses, plummeted from 72 ships at 111,683 tons in July to only 46 ships at 86,981 tons in December.[cxlii]

By August 1917 the convoy system had been systematically implemented in all three maritime theatres, the North Sea, Atlantic Ocean, and the Mediterranean

The Flanders UB and UC flotillas were, however, continually destroying Channel shipping at an average of 50,000 tons a month for the entire period and the Third Ypres offensive had failed to capture Passchendaele, and critically, the U-boat bases along the Belgian coast. Despite these set-backs there was room for hope. In the Atlantic the tonnage loss rate fell from 550,000 tons in April, to only 165,000 tons in November. 37 U-boats were destroyed during the second half of 1917, 16 by mines, the total equivalent to 7.4 boats a month, nearly matching the commission rate for new U-boats, 8.8 per month.[cxliii]

Counter-blockade submarine U151, 1,500 tons displacement, first of seven initially designed for use as blockade runners and in April 1917 converted to an Atlantic battle submarine, entering service in July 1917.

In September there were 139 submarines operating, the wartime peak, allowing for an increased daily average of 56 U-boats in October, more than the 39 at sea in November or the 48 in December.[cxliv] With nearly fifty U-boats continuously at sea every day, and new long-endurance U-boat cruisers plumbing the Atlantic to the tune of 52,000 tons per three month cruise, as U155 achieved in the fall of 1917 (10 steamers & seven sailing ships), the submarine war was far from over.[cxlv]

Daily average of U-boats at sea & total (Allied, Neutral & British) tonnage sunk on average per boat. The sinking rate was cut almost in half between March and December 1917. Furthermore the average daily number and size of vessels sunk was falling: whereas in March 889 tons of British shipping was on average destroyed each day, by August that number had fallen to 485 tons, & half again to 284 tons by December. In March – June the average size of each ship sunk was 5,084 tons gross, falling to 4,342 tons in July – October. Tarrant, The U-Boat Offensive, p. 58

Convoy Battles, October – December 1917

From Jellicoe’s perspective, the Royal Navy was engaged in an unprecedented destroyer and submarine action with the German Navy, with the possibility for a High Sea Fleet sortie at any time. Early in the morning of October 17, German light cruisers raided a west-bound Scandinavian convoy of 12 (two British, one Belgian, one Danish, five Norwegian, three Swedish) that had departed Marstein in the company of two destroyers, HMS Strongbow and Mary Rose.[cxlvi] Just after 6 am on the 17th, Strongbow spotted two unidentified vessels on a converging course. In fact, these were the 3,800 ton German minelaying cruisers SMS Brummer and Bremse, with orders to mine the Scandinavian convoy routes.

SMS Brummer, minelaying cruiser that along with sistership SMS Bremse, attacked a Scandinavian convoy on 17 October 1917 & HMS Strongbow, destroyed by SMS Brummer & Bremse at the action of 17 October 1917

The light cruisers proceeded to make short work of Strongbow and Mary Rose with their 15 cm guns.[cxlvii] The trawlers Elise and P. Fannon, armed with only one 6 pdr gun apiece, along with three unarmed steamers, managed to escape and retrieve Lieutenant Commander Brooke, CO of the Strongbow and others, from the water.[cxlviii] The enemy cruisers destroyed the remaining nine merchants in the convoy.[cxlix]

Locations of major minefields, Tarrant, The U-boat Offensive, p. 62 & The chaotic minefield situation in the Heligoland Bight, 17 November 1917, from Newbolt, Naval Operations, vol. V, p. 168-9

On 17 November the Second Battle of Heligoland Bight took place when the First Battle Cruiser Squadron, under Rear Admiral Phillimore, a component of Admiral Pakenham’s Battle Cruiser Force, intercepted a group of High Sea Fleet minesweepers that were attempting to clear the edge of the Bight minefields.[cl] Rear Admiral Phillimore’s HMS Repulse group pursued the minesweepers, but the Germans deployed a large smoke screen that successfully covered their escape.[cli]

HMS Repulse or Renown at steam, by William Weyllie. & Second Battle of Heligoland Bight, 17 November 1917, also by Wyllie

HMS Repulse or Renown at steam, by William Weyllie. & Second Battle of Heligoland Bight, 17 November 1917, also by Wyllie

On 11 December Admiral Scheer ordered Commander Heinecke’s Second Flotilla (Torpedo Boat Flotilla II), comprising the largest and fastest destroyers in the fleet,[clii] to raid Britain’s merchant convoys. The Fourth Half-Flotilla was to attack shipping near Newcastle, while the Third Half-Flotilla raided the Scandinavian Bergen-Lerwick line. During the winter darkness early on 12 December, the Fourth Half-Flotilla destroyers (B97, B109, B110 & B112), moving north up the coast, encountered the stragglers from a southbound coastal convoy out of Lerwick, Shetlands, and torpedoed two transports, the Danish Peter Willemoes and the Swedish Nike and sank a third small coastal steamer shortly afterwards.[cliii] The Fourth Half-Flotilla then withdrew for its rendezvous with the light cruiser SMS Emden at 5:15 pm.[cliv]

German destroyers in formation, from Goldrick, After Jutland (2018), photo 9.1

The complexities of night-time communication in crowded sea-lanes meant that no clear indication of what was happening reached the Admiralty. Furthermore, the poor weather conditions and dearth of coastal lighting (suppressed except at specific times at Admiralty orders) resulted in the Third Half-Flotilla becoming lost and eventually approaching the Norwegian coast.[clv]

G101-type German destroyer, c. 1916

So it was with complete surprise that the daily convoy from Lerwick to the Marstein lighthouse, escorted by destroyers HMS Pellew and HMS Partridge, plus four armed trawlers, at 11:30 am south-west of Bjorne Fjord, encountered the German destroyers of the Third Half-Flotilla, under the command of Korvettenkapitan (Lieutenant-Commander) Hans Kolbe, a powerful force composed of SMS G101, G103, G104 & V100.[clvi] Lieutenant-Commander J. R. C. Cavendish of the Pellew, when the unknown destroyers approaching the convoy did not answer his signals, transmitted a warning notice to Beatty informing the C-in-C of the expected enemy contact (a signal actually received by the armoured cruiser HMS Shannon and its group, about sixty miles away), and then ordered the convoy to scatter.[clvii]

The 12 December 1917 convoy action, from Scheer’s High Sea Fleet, p. 383

Pellew and Partridge placed themselves between the German destroyers and the convoy hoping to buy time.[clviii] Kolbe’s force destroyed Partridge with gunfire and torpedoes until it sank. Pellew, partially disabled by gunfire, was lost in a storm and LTC Cavendish was able to navigate the destroyer towards the Norwegian coast while Kolbe turned on the convoy (six merchants, four trawlers) and annihilated it.[clix] Although the Partridge distress report was received by HMS Rival and then transmitted to the HMS Birkenhead group (3rd Light Cruiser Squadron) south of Norway, Kolbe’s force managed to slip east past the picket line shortly after sunset.[clx]

Chart of 12 December 1917 destroyer raid on the Scandinavian convoy route, from Marder, FDSF, IV

Chart of 12 December 1917 destroyer raid on the Scandinavian convoy route, from Marder, FDSF, IV

While this example demonstrated that Germany’s surface assets were very much still a risk to the convoy system, another encounter a week later with U-boats operating near a convoy assembly point highlighted the multidimensional nature of the battle.

A convoy of 17 departed Falmouth in stormy weather at 11 am on 18 December, screened by several trawlers. When the convoy was clear of the Channel and off Prawle point at 1:30 pm, the SS Riversdale was torpedoed. At noon the C-in-C Devonport, receiving reports of sunk merchant ships, ordered all merchant traffic between Plymouth and Portland to be halted, a condition that remained in force until 8 pm, and then again from 5:15 am.[clxi]

The 7,046 ton Cunard liner SS Vinovia was the next to be torpedoed, off Wolf Rock an hour later, with nine lives lost.[clxii] The Rame Head wireless-telegraphy (W/T) station reported a sighting, and the C-in-C Devonport ordered the trawlers in F section to investigate. These were the Mewslade and Coulard Hill. These hydrophone equipped vessels established a hydrophone picket, but did not locate any submarines.[clxiii] Meanwhile, airship C23, which had been despatched to investigate the Rame Head W/T contact, discovered that the French steamer St. Andre had also been torpedoed, sometime around around midnight.[clxiv]

UC100, UCIII-type coastal minelayer submarine, from Tarrant, The U-boat Offensive (2000)

Lieutenant John Lawris RNR, in the sailing ship Mitchell, encountered a U-boat surfacing in windy weather off the north Devon coast. When, at 10:10 am, a submarine surfaced in front of the Mitchell Lt. Lawris opened fire, multiple shell hits causing the U-boat to dive. Although the trawler Sardius raced to support the Mitchell, the submarine was already gone.[clxv] Mitchell relayed this information to the Trevose Head W/T station at 10:25, and the report was broadcast around the region, where it was received at Penzance, Falmouth, Newlyn and elsewhere.[clxvi] The rush of W/T communication amidst the flurry of sighting reports caused communication delays. One Falmouth flotilla, carrying out hydrophone investigations of sightings, did not receive a sinking report until five and half hours after the event.[clxvii]

At 4:00 pm the Prince Charles de Belgique, a Belgian steamer, was attacked by a submarine eight miles from the Lizard. Luckily the torpedo missed, whence the U-boat was spotted by a Newlyn NAS seaplane cruising overhead at 500 ft. The seaplane carried out a bombing attack but was unsuccessful. Simultaneously at 4 pm, the trawler Take Care, while protecting the Brixham fishing fleet, spotted a submarine near Berry Head, although no further sightings were made. Several hours later trawler Lysander was picking up the survivors of the torpedoed Norwegian steamer Ingrid II, which had been enroute to Cardif for repairs.[clxviii] The Alice Marie was sunk next, sometime before midnight, then the Warsaw at 1:20 am, and then at 4 am the Eveline. The trawlers Rinaldo and Ulysses could do nothing to intervene, dashing between reports and unable to make firm detections with their hydrophones.[clxix]

A significant score of ships destroyed, and no submarine caught in the act. The impact of A/S measures continued to be essentially random, thus when UB56 crashed into a mine in the English Channel it became the only German casualty associated with the 18 December action.[clxx] Ten merchant ships of three nations had been lost, but the convoy, reduced to 16, still crossed successfully.

St. Paul’s and Blackfriars Bridge, by William Wyllie.

These battles and others like them demonstrate that as 1917 came to a close the Royal Navy had to strengthen and refine its procedures for convoy escort and ASW. Outside of the Mediterranean, the English Channel, Irish Sea and the Scandinavian corridor were all vulnerable to attack, especially near the as yet unescorted coastal routes.

Resolution: Attacks on the Belgian Submarine Bases & the Defeat of the U-boats in 1918

When 1918 opened the convoy system had been widely adopted and plentiful resources were being supplied to the regional commanders. The coastal space, however, had become highly contested. A German surface raid attack near Yarmouth on 14 January involved 50 vessels of various kinds, but was driven off by Commodore Tyrwhitt’s Harwich Force.[clxxi] Despite the ongoing surface and submarine battle, crucially, merchant sinkings were well below crisis levels and falling.[clxxii] In December 1917 the German Admiralty made Vice Admiral Ritter von Mann-Tiechler head of a dedicated U-boat office, recognition of ad hoc nature of the previous year of unrestricted submarine warfare.[clxxiii]

Sir Eric Campbell Geddes as Vice Admiral and First Lord of the Admiralty, 1917, photograph by Walter Stoneman

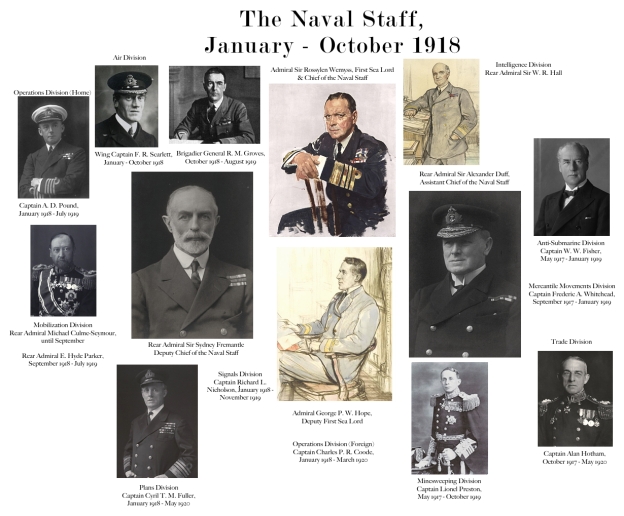

Naval Staff reforms c. January 1918, from Nicholas Black, The British Naval Staff In The First World War (2011)

Naval Staff reforms c. January 1918, from Nicholas Black, The British Naval Staff In The First World War (2011)

The Naval Staff as organized in January 1918 for the Geddes – Wemyss administration, from Jellicoe, Crisis of the Naval War (1920), p. 27

The Naval Staff as organized in January 1918 for the Geddes – Wemyss administration, from Jellicoe, Crisis of the Naval War (1920), p. 27

Next to fall from the famous Geddes axe was Vice Admiral Bacon, the long serving SNO Dover. Wemyss appointed Rear Admiral Roger Keyes in his place on 1 January 1918. Captain Wilfred Tomkinson became Captain of the Dover Destroyers.[clxxvii] The arrangement of the Dover Barrage, as it had been under Bacon, was expanded with a new system of illumination, authored by Wing Commander F. A. Brock (RNAS), son of the Brock of Brock’s firework (and explosive bullet) manufacturer, coinciding with a new patrol scheme, whereby 80 to 100 destroyers and auxiliaries were constantly patrolling the Straits by day and night.[clxxviii]

The positions of the Channel mine net and Folkestone – Gris Nez minefields in 1918, from Tarrant, The U-boat Offensive, 1914-1915 (2000)

Between 19 December 1917 and 8 February 1918 four U-boats were mined in the Channel, and UB35 was depth-charged by HMS Leven.[clxxix] The increased danger was so significant that Commodore Michelsen was forced to prohibit the use of the Channel route and instead endorse the northern route around Scotland, effectively adding five days of transit to the U-boats’ cruise.[clxxx]

The Flanders command launched another anti-shipping sortie on 14 January with 14 destroyers, although in the event no merchant ships were encountered.[clxxxi] A month later, on 13 February, Commander Heinecke’s Second Flotilla was despatched to attack the Dover – Calais barrage, in particular, the lights that since December 1917 had drastically increased the risk to transiting U-boats.[clxxxii] Heinecke’s destroyers departed in thick fog, and anchored overnight north of Norderney.

Dover trawlers and motor-launches, from Steve Dunn, Securing The Narrow Sea (2017)

After working around to the English coast the attackers, eight in total, split into two half-flotillas and waited until night, and then, around 12:30 am on the 15th, began their raid against the well lit and heavily defended cross-Channel barrage. Attaining complete surprise, Heinecke’s force (Fourth Half-Flotilla) destroyed, according to Scheer, a searchlight vessel, 13 drifters, a U-boat chaser, a torpedo boat and two motor-boats, while the other half-flotilla (Third Half-Flotilla), working the southern end of the barrage, sank 12 trawlers and two motor-boats. Steve Dunn and James Goldrick give the accurate figure of seven drifters, one trawler sunk, with three drifters one paddle steamer damaged.[clxxxiii]

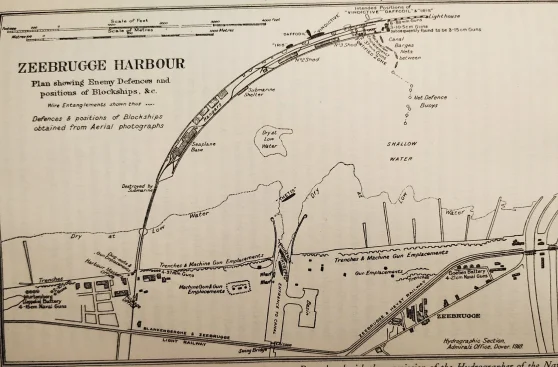

Dover’s new C-in-C Admiral Roger Keyes now conducted the long-planned Flanders coast raid on 22 April.[clxxxiv] Although the blockships meant to obstruct the Zeebrugge harbour were only effective for a few days, the daring raid was described as a triumph by the press, with eight Victoria Crosses being awarded to the participants.[clxxxv] A further attempt to block the Ostend canal was attempted on 9-10 May, with likewise limited results.[clxxxvi]

On 23 April 1918 the High Sea Fleet launched a planned raid against the Scandinavian convoy route.[clxxxvii] This was a major operation involving the battlecruisers of the Scouting Group under Admiral von Hipper, in addition to light cruisers and destroyers, supported by Scheer’s main force. As the advanced group cleared the Heligoland minefields, however, SMS Moltke threw a propeller and suffered a turbine failure that ultimately damaged the engines and caused a breach in the hull. The battlecruiser had to be taken in tow by SMS Oldenburg.[clxxxviii]

24 April 1918 High Sea Fleet sortie, from James Goldrick, After Jutland (2018), map 13.1

The Grand Fleet was notified by Room 40 that the High Sea Fleet was out of harbour and Beatty prepared the fleet for sea,[clxxxix] although there was no chance the British could catch the Germans before they returned to harbour.[cxc] Later that evening, after being restored to its own power, Moltke was torpedoed by RN submarine E42, but managed to return safety of the Jade.[cxci] The fleet operation had failed to locate any convoys and the High Sea Fleet would not sortie again until it sailed for internment on 24 November 1918.

While the U-boats’ areas of operation were slowly being squeezed by increasingly comprehensive convoys and sophisticated hydrophone and aerial sweeps, the bombing campaign by RNAS Dunkirk, and after 1 April 1918, RAF No. 5 Group, against the Flanders U-boat bases was renewed. Wing Captain Charles Lambe’s 27 May operating orders called for the No. 5 Group (Dunkirk) to bomb the Bruges docks twice a day, both day and night.[cxcii] Indeed, 70 tons of bombs were dropped on Bruges and Zeebrugge during May 1918.[cxciii]

Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) naval air, airship, and training establishment map, March 1918, and Royal Air Force (RAF) Home Defence Groups.

From mid-June until the end of August, 86 tons of bombs were dropped on Zeebrugge, Ostend and Bruges by No. 5 Group, with another 49 tons dropped by other RAF squadrons.[cxciv] Between February 1917 and November 1918 the various Allied bombing forces (the US Northern Bombing Group had been forming since June 1918),[cxcv] managed to drop 524 tons of bombs on Zeebrugge, Ostend and Bruges, and, although the Bruges electrical works were destroyed and the Zeebrugge lock gates targeted, only three submarines were damaged by the bombing programme.[cxcvi]

The U-boats, for their part, had been forced once again to change tactics, focusing on the lightly escorted outbound traffic returning across the Atlantic to America. During the summer of 1918 the U-boats, by expanding their area of operations into the western and southern Atlantic, scored a series successful sinkings.

Powerful 2,000 ton U139 – U141 ‘cruiser’ type developed for long-range operations in the Atlantic, armed with two 150 mm cannons and 19 torpedoes for its six torpedo tubes. & U140, double-hulled 12,000 nm range 2,000 ton submarine crewed by six officers and 56 men, armed with 8.8 cm and 10 cm guns and six torpedo tubes, four bow and two stern, from Eberhard Moller and Werner Brack, Encyclopedia of U-boats from 1904 to the Present (2004), p. 39

Allied shipping losses in the Channel and Western Approaches for 1918

However, as the return voyage traffic was empty of supplies or troops the impact on the war was marginal in comparison to the 1.5 million American soldiers that successfully crossed the Atlantic.[cxcvii] Although shipping losses remained in the 300,000 ton/month range for the first eight months of 1918, with a high of 368,750 tons sunk in March, followed by a low of 268,505 tons in June, the sinking rate was not high enough to cripple Allied shipping.[cxcviii]

Convoys in 1918, by John Everett

Convoys in 1918, by John Everett

32,000 ton White Star liner Justicia, sunk 19 – 20 July 1918, despite escort, by the combined efforts of UB64, U54, with UB124 in support (damaged by escorts and then scuttled).