Early 19th Century oil painting of Sir George Pocock, based on a c. 1761 painting by Thomas Hudson.

The Career of Admiral Sir George Pocock

A distant figure in our time, Sir George Pocock was a consummate naval officer, with victories in both the War of Austrian Succession and the Seven Years War, responsible in the latter for securing command of the Indian Ocean during 1759, and for Britain’s greatest maritime operation of the 18th century – the capture of Havana in 1762. Closely associated with controversial figures such as Lord Clive, John Byng and the Earl of Albemarle, Pocock was marginalized in the historiography during the 19th century in comparison to the towering figures of Anson, Rodney, Hawke and Boscawen. Pocock nevertheless played an integral role in several of Britain’s most important maritime operations and his well deserved reputation for courage, steadfastness and imperturbability encourage modern reappraisal.

The Young Gentleman

George Pocock was born on 6 March 1706 at Thames Ditton, Surrey, the son of the Reverend Thomas Pocock and his wife Joyce Master. Thomas was a Royal Navy chaplain who ministered to the Royal Hospital at Greenwich.[i]

HMS Superb, captured French Superbe of 1710, flagship of Admiral George Byng, Pocock’s first posting in 1718

Pocock’s naval career began in 1718 at the age of twelve when he joined HMS Superb (64), the captured French warship then the flagship of Admiral George Byng (Viscount Torrington) – himself married to one Margaret, Joyce’s sister. Superb’s flag captain was Streynsham Master, Pocock’s uncle. Pocock was accompanied to sea by his cousin John Byng (of eventual Minorca infamy) who was also beginning his career aboard the flagship of the Admiral, his father.[ii] Pocock’s path was thus smoothed by his close association with senior officers and his extended network of relatives and relations.

Both Byng and Pocock were aboard Superb when it fought at the battle at Cape Passaro, Sicily, 11 August 1718.[iii] From here Pocock spent three years aboard the hospital ship Looe and a further four years aboard the warships Prince Frederick (70) and Argyle (50).

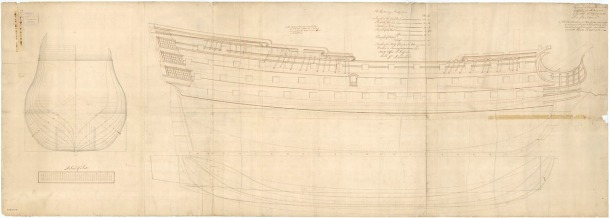

HMS Namur, 90 gun 2nd rate in which Pocock was made First Lieutenant in August 1732.

The Portrait of a Naval Officer, from Lieutenant to Post Captain

Pocock made Lieutenant on 19 April 1725 (other sources say December 1726), and was stationed aboard HMS Burford (70), followed by Romney (54), and then Canterbury (60).[iv] Pocock was next appointed to HMS Namur (90) the flagship of Admiral Sir Charles Wager, and in August 1732 he was promoted to First Lieutenant. Pocock’s first command was the fireship Bridgewater, to which he was appointed on 26 February 1733.

1719 establishment frigate similar to the 1727 rebuilt 20 gun 6th rate HMS Aldborough, Pocock’s first command in 1738.

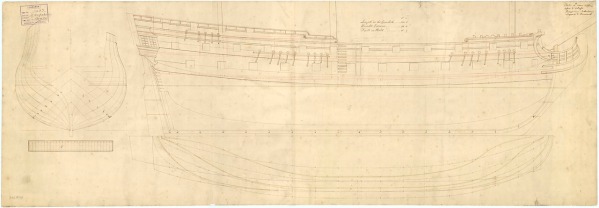

Pocock made Commander in February 1734,[v] and after four years of service was promoted, on 1 August 1738 at the age of 32, to Post Captain with command of the frigate Aldborough (20), first built in Pocock’s birth-year of 1706, then rebuilt in 1727.[vi] Thus, Pocock was stationed in the Mediterranean under Rear Admiral Haddock. The squadron in which Pocock served secured several lucrative Spanish captures following the declaration of war in 1739.[vii] Pocock continued in the Mediterranean until 1741, and then he returned to England.

HMS Woolwich in 1677 as a 54 gun 4th rate, by Willem van de Velde, rebuilt in 1702 and again in 1736 as a 50 gun ship, to which Captain Pocock was appointed in 1742.

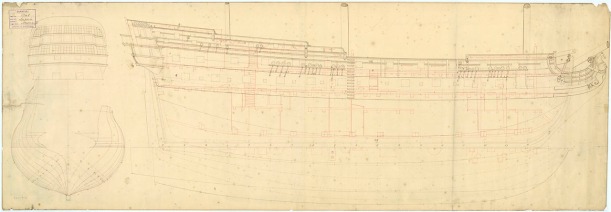

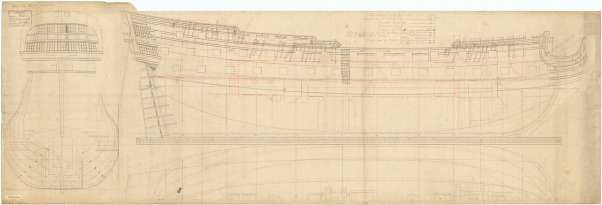

In August 1742, now 36, Pocock was appointed to the Woolwich (50), a heavily rebuilt 4th rate originally completed in 1675.[viii] He was transferred briefly to the Shrewsbury and then in 1744 (or January 1743) he was appointed to the Sutherland (50) a new 4th rate only three years out of the yards, in command of which he was despatched to the East Indies, convoying British East India Company (BEIC) ships. These 4th rates of the 1733 and 1741 establishment were designed by Sir Jacob Acworth, the Surveyor of the Navy between 1715-1749. Although plentifully armed,[ix] they were nevertheless under-gunned due to a shortage in heavier ordnance that prevailed in Britain during the 1730s, and have further been criticized as cramped and overly expensive.[x]

Lines of the ‘Sutherland’-type 50 gun 4th rates built in 1741, Pocock’s command in 1744.

Block model of HMS Preston a 1733 establishment 50 gun cruiser built in 1742. The 853 ton 4th rate was crewed by 300 men and equipped with 22 18-pounders, 26 12-pounders, 14 6-pounders on the quarterdeck and four 6-pounders on the forecastle.

Model of 50-gun cruiser circa 1725, similar to the newer Sutherland commanded by Captain Pocock in 1744.

Pocock was ordered to the African coast in October 1744, but his sailing from Plymouth was delayed due to trouble fitting and manning the Sutherland and the operation was not carried out until April 1745 (Pocock arrived at Madeira on the 27th of that month).[xi]

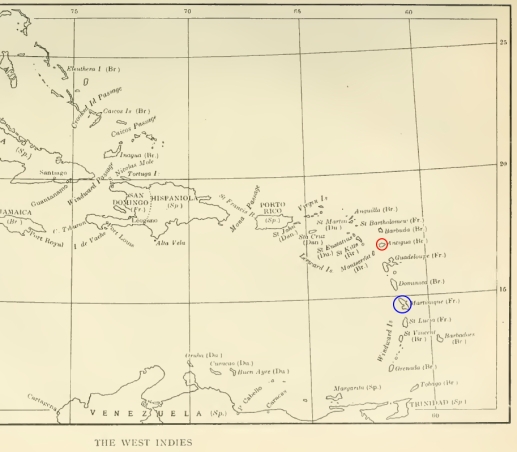

The eastern Caribbean during the War of Austrian Succession (1740-1748), the principle convoy assembly points at Antigua (British – red), and Martinique (French – blue) circled.

Map of Antigua made in 1780 and drawn from late 1740s surveys, base of Britain’s Leeward Island Station during the 18th century

Pocock was eventually assigned to the Barbadoes and Leeward Islands station under Commodore Edward Legge, who had been appointed to the Leeward Island station command on 24 October 1746.[xii] The Sutherland, arrived at Antigua on 28 April 1747. Under Legge’s command, Pocock’s Sutherland was employed on trade defence, convoy protection and shipping interdiction missions, working with the other cruisers on station in pairs. Sutherland worked alongside HMS Captain (70), Suffolk (70), Dragon (60), Sunderland (60), Dreadnought (60), Gosport (44), and assorted frigates and sloops against the French convoys sailing from Martinique.[xiii]

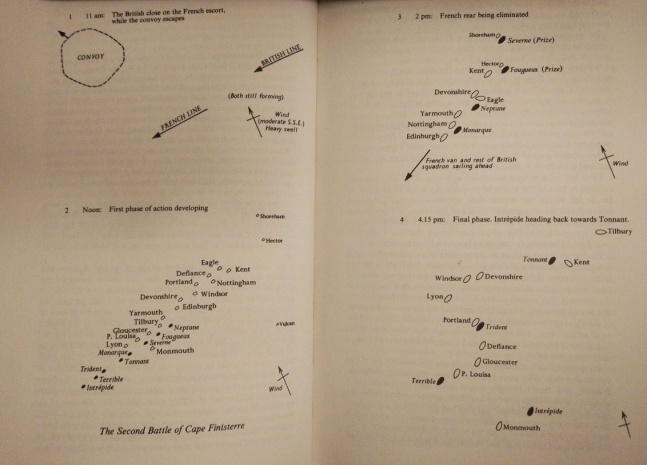

Second Battle of Cape Finisterre, 14 (25) October 1747, Rear Admiral Hawke’s action scattered a large French convoy that proceeded to the West Indies where it was intercepted by Pocock’s Leeward Island’s squadron in November.

Pocock was thrust into command when Commodore Legge became seriously ill in August and then died on 18 or 19 September 1747 at the age of 37. Pocock, the senior captain, now succeeded Legge as C-in-C.[xiv] Pocock’s singular achievement came in November with the capture of a scattered French convoy, the result of Rear Admiral Hawke’s action off Cape Finisterre, 14 (Julian, 25, Gregorian) October 1747.[xv] Pocock’s small squadron of cruisers, frigates, sloops and privateers captured as many as 40 merchant ships – and 900 prisoners – although a further 66 merchant ships from the original convoy of 252 made it to Martinique.[xvi]

Pocock returned to England, having been relieved in the Caribbean in May 1748 by Rear Admiral Henry Osborne. Shortly afterwards, on 18 October 1748, the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle ended the War of Austrian Succession.

Pocock, now a wealthy – although not yet rich – man as the result of his shipping captures, moved into an apartment on St. James Street, London. In 1749, at the age of 43, Pocock was painted by Thomas Hudson.

Commodore George Pocock, 43, painted by Thomas Hudson in 1749

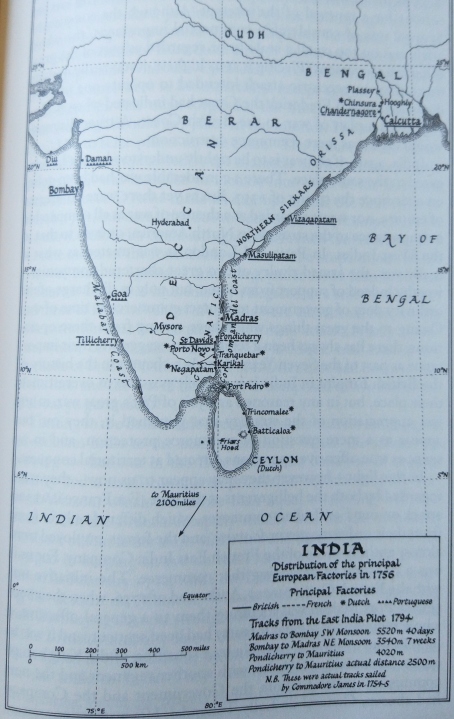

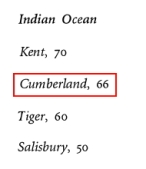

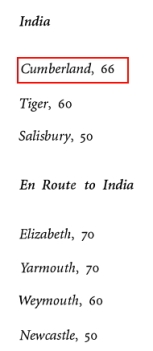

Pocock had no command until 1754 when he was appointed to the Cumberland (66) for home duty, before being transferred to the Eagle (60) – although this ship was badly damaged in a storm, and Pocock returned to the Cumberland – to sail on 24 March with Rear Admiral Charles Watson and 400 troops, destined for the East Indies.[xvii]

Admiral in the Indian Ocean

The Seven Years War with France provided Pocock with the opportunity he needed to resume his naval career. Cumberland arrived in the Indian Ocean in September 1754 and Pocock’s role in the global conflict began at sea on 6 January (or 4 February) 1755 when he was advanced to the rank of Rear Admiral of the White.

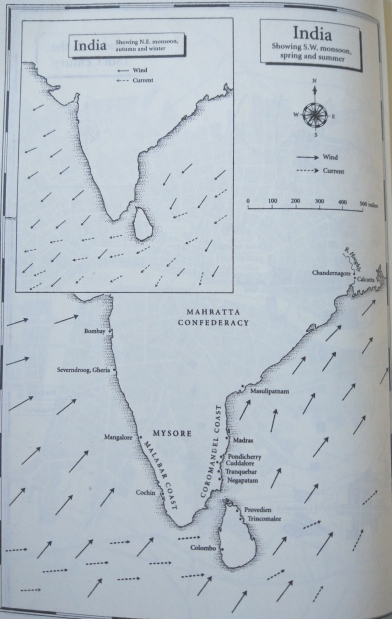

Maps of India, showing European trade stations during the Seven Years War, and prevailing annual weather during.

Pocock sails for India in early 1755 aboard HMS Cumberland

The capture of Geriah, 12 – 13 February 1756, by Dominic Serres in 1771. Rear Admiral Watson’s flagship, HMS Kent is in the centre, with Pocock’s Cumberland to its right, facing backwards.

Cumberland reached Bombay on 10 November 1755. Watson and Pocock were soon engaged fighting the pirate Tugalee Angria, who sortied from his base at Geriah near Goa. Rear Admiral Watson in Kent, with Pocock as his second in command in Cumberland, transported a detachment of troops under Lieutenant Colonel Robert Clive to Geriah, arriving on 12 February 1756. Clive’s soldiers were landed in the evening while Watson’s force put Angria’s pirate flotilla to the torch and bombarded his base. Although Angria himself escaped, the pirate’s base and treasure (including £130,000 of spices, jewels, and other valuables) were captured. Watson returned to Madras at the end of April, and Pocock was promoted to Rear Admiral of the Red on 4 June 1756.

Almost two weeks later Suraj-ud-Daula, the nineteen year-old nawab of Bengal, deployed 30,000 men to surround Calcutta, where Britain’s Fort William was garrisoned by a mere 500 soldiers. The fort fell on 20 June, the captured British prisoners suffering their ignominious fate in the notorious Black Hole of Calcutta – more than half dying from suffocation.[xviii]

News of this disaster reached Madras on 16 August, where Watson and Pocock were stationed. A relief expedition was organised but it was unable to sail until October when the prevailing winds made progress tortuously slow. Pocock’s mission, working with C-in-C Watson, was to escort a landing force to Calcutta, but the squadron did not arrive until 8 December,[xix] while Pocock’s Cumberland had became separated from the attacking squadron and was running short on supplies. By the time Pocock reached Calcutta, in January, Calcutta and the surrounding forts had already been recaptured by Watson’s landing force of 700 regulars, 600 sailors and marines, and 1,200 sepoys, commanded once again by Colonel Robert Clive. Nevertheless, Pocock was promoted to Vice Admiral of the White in February 1757 (or possibly earlier on 8 December 1756).

Clive, after defeating Suraj-ud-Daula in open battle and securing his cooperation through a peace treaty on 9 February, was eager to advance on towards the French trade post at Chandernagore. Conveniently, it was now that news arrived from Europe that war had indeed been declared between France and Britain, so Clive and Watson set off upriver.[xx]

Rear Admiral Watson’s force – Kent, Tiger (under Pocock) and Salisbury – bombarding Chandernagore on 23 March 1757, by Dominic Serres, 1771

Pocock, arriving at Calcutta shortly after this, followed up the Hooghly river in a boat and barge flotilla. He arrived on 22 March 1757 and immediately took command of the warship Tiger (60), which along with Kent (70) and Salisbury (50) had managed to work themselves upriver. The bombardment was opened the following day. In this violent action Pocock himself was wounded when he was hit by flying splinters (Salisbury failed to get into position while Tiger suffered 13 killed and 54 wounded; Kent another 19 killed and 74 wounded).[xxi] Following the surrender of Chandernagore, Clive went on to defeat Suraj-ud-Daula – who had once again turned against the BEIC – in the famous battle at Plassey, 23 June 1757.[xxii]

On 15 or 16 August 1757 Rear Admiral Watson died of fever at Calcutta and Pocock assumed command of the entire East Indies squadron. Also at this time, Pocock learned of the court martial and execution of his cousin, Admiral John Byng, stemming from the latter’s failure to recapture Minorca (20 May 1756).

Royal Navy reinforcements arrive in 1757 & Pocock becomes C-in-C East Indies. Note the loss of Kent.

The Duel

Early in 1758 Pocock left Bengal for Madras, where he was met by Commodore Charles Steevens with reinforcements: four ships-of-the-line and a frigate,[xxiii] and on 5 February (or 31 January) Pocock was promoted to Vice Admiral of the Red.[xxiv] The essence of fleet strategy in the Indian Ocean revolved around securing trade from the west coast of the sub-continent between April and September, before the monsoon season began, and no doubt the French would do what they could to interdict this trade.

Indeed, intelligence soon arrived that the French were sending reinforcements to counter-attack. A small force led by the skilled Anne Antoine Comte d’Ache de Serquigny had been despatched from Brest on 3 May 1757 (although three of d’Ache’s four ships-of-the-line had to be diverted to Louisburg).[xxv]

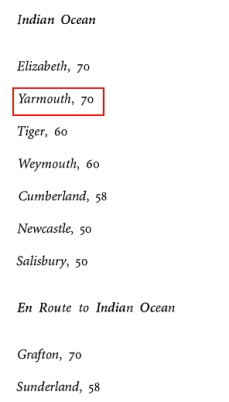

Build up of forces in the Indian Ocean during 1758, Pocock battles the Comte d’Ache for control of the East Indies.

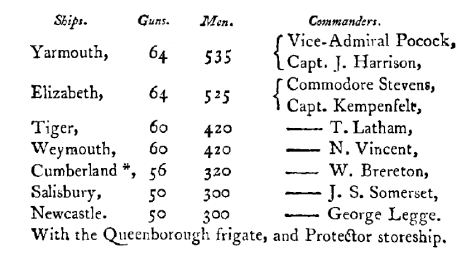

Pocock’s East Indies squadron after being reinforced by Commodore Stevens in early 1758. Note Captain Richard Kempenfelt’s presence as Commodore Stevens’ flag-captain aboard HMS Elizabeth.

Pocock flew his flag from HMS Yarmouth (70) and put to sea on 17 April, passing Negapatam and Fort St. David, and on 28 April Pocock’s squadron of seven intercepted the Comte d’Ache’s squadron of nine (eight total owned by the French East India Company, some acquired enroute at Mauritius) near Cuddalore.[xxvi] D’Ache had previously arrived at Fort St. David where he forced two of Pocock’s detached frigates to run aground, whence the British crews torched the ships to prevent capture.[xxvii]

D’Ache was escorting 1,200 French reinforcements (four battalions) under the command of the Comte de Lally (Lieutenant General Thomas Arthur Lally, baron de Tollendal, descendent of an Irish émigré; a solider of fortune) destined for Pondicherry. While Pocock was preparing to close with d’Ache, the Comte despatched Lally-Tollendal in the Comte de Provence (74) to make for Pondicherry, leaving d’Ache with only eight ships to fight Pocock’s seven.

HMS Yarmouth (70), Pocock’s command in 1758-9

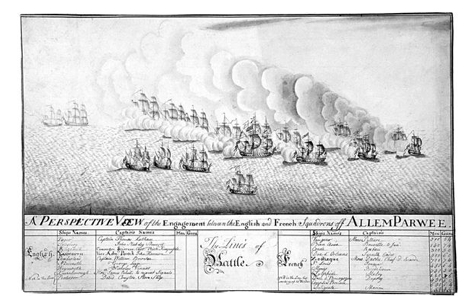

View of Pocock’s first action with d’Ache, 29 April 1758

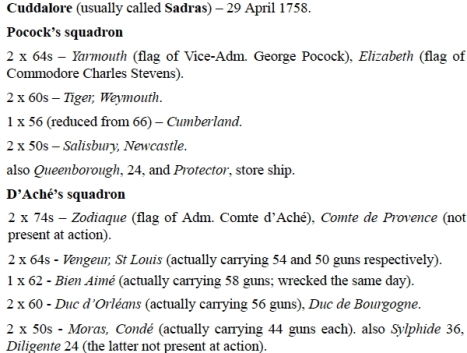

Order of battle for Cuddalore/Gondelour

Between 2:15 and 3 pm on 29 April Pocock steered directly for d’Ache’s flagship, the Zodiaque, and although he was receiving incoming fire from the French line, did not return fire until within pistol-shot.[xxviii] At the decisive moment he signaled for close action. In the ensuing battle (known as the battle of Gondelour in French and Cuddalore or Sadras in English), only four of Pocock’s ships engaged (leaving Cumberland, Newcastle, and Weymouth behind, and generating court martials for the three hesitant captains), and by the time the three laggard ships had caught up the British had been badly damanged, allowing d’Ache to make good his escape, limping into Pondicherry, where the Comte de Lally had already arrived.[xxix] Although Pocock flew the signal for general chase it was clear the British, with many sails and masts shot away, could not pursue and thus only the frigate Queenborough was sent ahead to try to locate the French squadron during the night, but to no avail.[xxx] D’Ache later lost the East Indiaman Bien-Aime (58) when it crashed ashore.[xxxi]

Nevertheless, Pocock’s force had inflicted numerous casualties: 162 killed and 360 wounded (or near 600 killed and wounded), in particular aboard d’Ache’s flagship. D’Ache, however, had done well himself, having achieved his objective of getting through to Pondicherry and had inflicted casualties of his own, primarily on the Yarmouth. Total British losses were 29 killed and 85 (or 89) wounded.[xxxii]

Pocock refitted at Madras and was prepared to sail on 10 May. Lally-Tollendal was on the move, however, and with 3,500 Europeans and another 3,000 Indian troops first captured Cuddalore and then laid siege to Fort St. David.[xxxiii] Pocock intended to relieve the siege of Fort St. David, but was unable to reach the outpost before it surrendered on 2 or 6 June, along with its garrison of 1,000.[xxxiv] Pocock’s normally cool temper was by now enflamed and upon return to Madras for victuals and water he ordered the court martials of Captains Vincent, Legge and Brereton, whom he held responsible for failing to engage on 29 April. Captain Vincent was relieved of his command, Legge was cashiered and Brereton reduced a year in seniority.[xxxv] The incident had stung Pocock – a man not easily shaken from his serene demeanour – and in later years he acknowledged this fact, coming to believe that he had been overly harsh in handing out these sentences.[xxxvi]

British and French order of battle off Negapatam, 3 August 1758. Notice the change of British captains following the court martials held in July.

Pocock put to sea again on 25 July and made a half dozen merchant ship captures before scouting the harbour at Pondicherry on the 27th. D’Ache, realizing he was about to be trapped, and with few provisions remaining, took his force of seven and a frigate and fled to sea, once again alluding Pocock’s general pursuit.[xxxvii] Pocock was, however, able to capture and burn a French ammunition ship that had been approaching Pondicherry.

Pocock sighted d’Ache on 1 August, and, although d’Ache skillfully delayed with a series of maneuvers all of August 2nd, Pocock was finally able to bring the Comte to action on the morning of the 3rd near Negapatam.[xxxviii] At 1:20 pm d’Ache decided it was time; his fleet drawn up in a crescent, and signaled to engage. Pocock followed suit, but was temporarily frustrated as d’Ache pulled his squadron away, firing chain shot at the English line, carrying away signals and masts.[xxxix] Pocock was determined to fight, however, and at 2:25 flew the signal for close action.

Captain Kempenfelt in the Elizabeth furiously attacked the Comte de Provence, temporarily setting it ablaze, then moving on to attack the Duc de Bourgoyne. Meanwhile, Pocock, in the Yarmourth, once again made for d’Ache’s flagship, the Zodiaque, and engaged it with a heavy fire, destroying the ship’s wheel. A gun exploded aboard the French flagship and in the confusion the Zodiaque collided with the Duc d’Orleans.[xl] With Yarmouth and Tiger closing in, d’Ache could see that the battle was turning against him – once again the daring French commander effected his escape, making for Pondicherry at 2:08 pm. Pocock signaled for general chase but, again, it was too late and d’Ache, although shaken, limped back into harbour. Pocock’s squadron suffered 200 casualties (31 killed and 116 – 166 wounded, including a slightly injured Pocock and Commodore Steevens – who had been shot by musket ball in the shoulder)[xli] to d’Ache’s 800 (250 killed and 600 wounded, amongst the latter including d’Ache himself as well as his flag captain).[xlii]

The strategic situation was liable to worsen as the French, on 9 March, had despatched additional reinforcements from Brest: Minotaure (74), Actif (64), and Illustre (64), as well as Fortune (54) from Lorient on 7 March. The Royal Navy was able to spare only Grafton (70) and Sunderland (60) sailing from England on 8 March.[xliii]

In the meantime, with the monsoon season set to arrive, Pocock made for Bombay to effect his repairs while d’Ache sailed for Mauritius (where he combined with Captain Froger de L’Eguille’s force of three-of-the-line). On 14 December Lally-Tollendal sieged Madras, but the siege was broken when Captain Kempenfelt, despatched by Pocock, arrived with frigates and several small craft loaded with stores and reinforcements, forcing Lally-Tollendal to raise the siege on 17 February 1759.[xliv]

Order of battle for Pondicherry

Battle of Pondicherry, 10 September 1759, the culminating battle between Pocock (top) and d’Ache (bottom), concluding with d’Ache’s flight from the Indian Ocean, securing India for Britain, much as Admiral Saunders and General Wolfe had done for Canada at Quebec (13 September), Commodore Moore had done for Guadeloupe in the West Indies (1 May), while Hawke destroyed the Brest fleet at Quiberon Bay (20 November) and Boscawen destroyed the Toulon fleet at Lagos (18 August): the string of victories that made 1759 Britain’s annus mirabilis.

Royal Navy casualties at Pondicherry

The situation remained a stalemate until 17 April 1759, when Pocock, with the weather once again favourable, sailed for Ceylon, hoping to intercept d’Ache at sea. For the following four months Pocock cruised, hunting for the French squadron.[xlv] Nevertheless, d’Ache was nowhere to be found and with provisions running low, Pocock set course for Trincomale on 1 September. However, within 24 hours of this decision, the frigate Revenge located d’Ache’s squadron at sea and hastened to inform Pocock. Hearing of this break of good fortune Pocock put about and signaled for a general chase. D’Ache, once again faced with his old nemesis, knew exactly what to do and proceeded to amuse Pocock at sea for three days, until the French commander disappeared into a bank of haze.

Pocock immediately made to blockade Pondicherry, hoping to intercept d’Ache should he try for that port – which was in fact d’Ache’s intention as he carried supplies for that critical base.[xlvi] Pocock arrived off Pondicherry on 8 September early in the morning; exactly eight hours before d’Ache. The French squadron was sighted at 1 pm and two hours later had been identified as 13 sail.[xlvii] Pocock continued ahead of d’Ache to prevent his escape and hounded the French squadron for 48 hours, finally closing on d’Ache’s line at 2:10 pm on 10 September. On this occasion (known as the battle of Pondicherry) Pocock had nine of the line against d’Ache’s eleven. D’Ache, with Yarmouth nearly within musket shot, saw that battle was now unavoidable and signaled for action, Pocock immediately following. An intense cannonade commenced until d’Ache pulled away not long after 4 pm. Once again Pocock’s ships were too badly damaged in their masts and yards to pursue. In the pitched battle d’Ache himself was again wounded (and his flag-captain killed), one amongst a total of 1,500 French casualties. Pocock’s forces had sustained 569 casualties (118 killed and another 66 dying afterwards, with another 385 variously wounded).[xlviii] Furthermore, Captain Michie of the Newcastle had been killed.[xlix]

Pocock ordered the frigate Revenge to follow d’Ache while the English made quick repairs at sea. The next morning the English sighted the French squadron but d’Ache again made sail, disappearing over the horizon. With Tiger and Cumberland under tow, Pocock made for Negapatam to repair, where he sent to Madras for reinforcements. At sea again on the 20th, Pocock set course for Pondicherry, where he found d’Ache at anchor beneath the fortress guns on the 27th – the French admiral had achieved his purpose and had landed his supplies. To Pocock’s frustration d’Ache proceeded to slip away, avoiding the still damaged English ships. Pocock returned to Madras. D’Ache, meanwhile, made for Mauritius, leaving the Royal Navy in control of the Indian Ocean, and clearing the way for the capture of Pondicherry itself, accomplished on 15 January 1761.

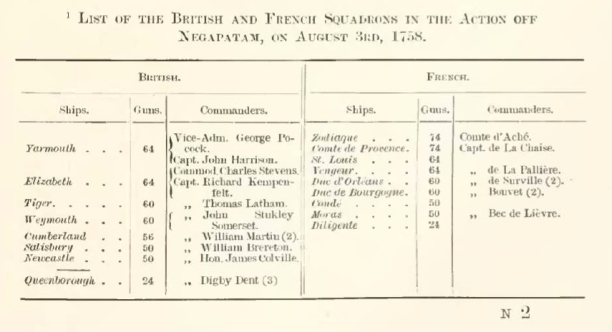

The East Indiaman “Pitt” engages St. Louis on 28 September 1758/9, by Dunn Lawson. St. Louis was a veteran of all three of d’Ache’s battles with Pocock. An artistic representation of the grand naval duel for India – if the exact particulars are perhaps imaginary.

Pocock, his health weakened by five years of relentless warfare in the East Indies, was ordered to hand-over his command to Commodore Steevens and return to London at the end of 1759. Pocock, however, felt his presence was still required and thus did not relinquish his command until April 1760. Back in London, he was rewarded with a marble bust commissioned by a grateful East India Company. Later that year, at the age of 54, Pocock was elected MP for Plymouth, and was subsequently knighted in March 1761. Pocock used his influence and his close relationship with Lord Anson to advance the interests of his commanders, being able to get James Hawker promoted, although not William Owen.[l] Pocock believed in rewarding those who had supported him, telling a follower that, “…if not too open and glaring an impropriety, I might rely on him.”[li]

Of Pocock’s actions in Indian waters Sir Julian Corbett wrote in 1907, “It is the fashion now merely to deride his battle tactics, which after three actions in eighteen months had failed to secure a real decision, though the tactics which would have secured a decision against a superior force determined to avoid one are never very clearly indicated. More just it would be to praise his vehement ‘general chases’, the daring and resolute attacks which in manner yielded nothing to Hawke’s, and above all for the strategical insight and courage which enabled him to dominate a sea which it was practically impossible for his inferior force to command.”[lii]

As for D’Ache, Pocock’s great antagonist in those distant waters, Pitt’s American strategy – culminating in the capture of Quebec while treating India as a holding action – had effectively terminated the threat from Mauritius. Clive now wrote that, “…this time the superiority of our force at sea, I take for granted, is beyond dispute, and of consequence our resources must be more than those of the French… A victory on our side must confine the French within the walls Pondicherry; and when that happens, nothing can save them from destruction, but a superior force at sea…”[liii] On 8 June 1760 news arrived at Mauritius informing D’Ache that the English were now preparing to shift their efforts to the Indies and thus that he should expect an operation with sizable forces against his island base, precluding any chance of further operations in Indian waters.[liv] D’Ache sent two frigates to inform Pondicherry of this unhappy fate and in January 1761 that last, all-important, French base in India capitulated.[lv]

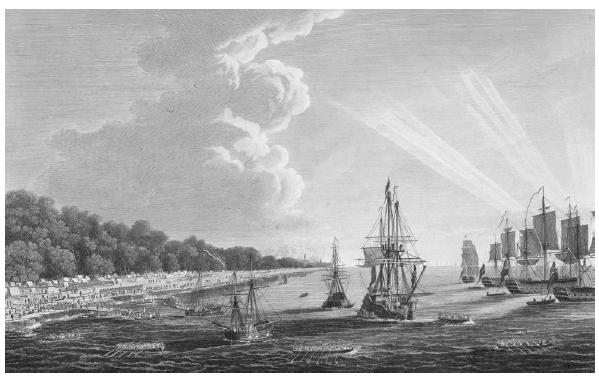

Return of a fleet into Plymouth Harbour, Dominic Serres, 1766

Triumph: The Havana Operation of 1762

War was declared against Spain on 4 January 1762 when the British government learnt of a treaty signed between France and Spain in August the previous year. The Cabinet, once again under the Duke of Newcastle, reached the decision to strike Havana on 6 January (a project Pitt had proposed before his resignation in October 1761), and Pocock, promoted to Admiral of the Blue, was selected for overall command, with Lieutenant General the Earl of Albemarle commanding the land forces.[lvi] Lord Anson drew up the plan, part of a two-pronged assault against the Spanish empire’s key colonial outposts: the Philippines and Cuba. On 7 January the Navy Board issued its request for transportation for the project and by the end of January the transports had been prepared and supplied for seven months rations. Pocock’s final orders arrived on 18 February.[lvii]

Lord Anson by Joshua Reynolds

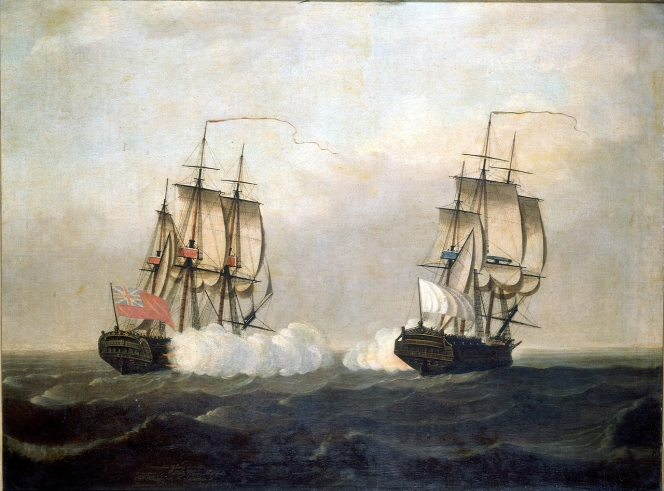

Caribbean during the Seven Years War, showing Pocock’s “Old Bahama” route to Havana.

Lines of HMS Namur, 90 gun second rate built in 1756, Pocock’s flagship for the Havana operation.

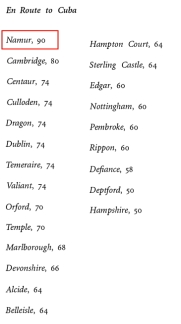

Pocock’s initial force as assembled (minus transports, etc) at Spithead.

By 26 February the entire force was prepared and assembled at Spithead (Albemarle described Pocock’s effort as “indefatigable”).[lviii] Pocock was to proceed with his forces to the Lesser Antilles, rendezvous with Major General Robert Monckton and Rear Admiral George Rodney, then sail to St. Domingue to collect additional forces for the landing before moving onto his objective. Pocock was to collect another four thousand regulars and American militia from New York, as well as a planned regiment of 500 blacks and 2,000 slaves from Jamaica, plus pilots from the Bahamas (who turned out to be inexperienced).[lix] Celerity was imperative as the onset of the hurricane season in August was bound to terminate operations, as was the prevalence of tropical disease, such as yellow fever.[lx]

Pocock, with second in command Commodore Augusts Keppel,[lxi] departed England with five sail, 67 transports, and 4,000 troops (four regiments – the 22nd, 34th, 56th and 72nd) on 5 March and arrived at Barbados on 20 April, before sailing to Martinique on 26 April, the latter island recently captured by Rear Admiral Rodney and Major General Monckton that January (St. Lucia had also been captured on 25 February under Captain Augustus Hervey). Rodney had already been informed by the arrival of the Richmond late in March that he was to prepare to join with Pocock – orders made difficult by an expected French assault on Jamaica, to intercept which Rodney had despatched ten ship-of-the-line under Commodore Sir James Douglas.

In the event, further intelligence confirmed that the French attack was not likely to take place and thus Commodore Douglas, aware of the all important nature of the Havana operation, decided to use his detached squadron to blockade the French base at Cape Francois, Saint Domingue, thus preventing the French and Spanish fleet from combining and possibly threatening the invasion force when it arrived.[lxii] Next Douglas despatched the Richmond to the Old Bahama Channel to prepare soundings and make sketches for the approach.

When Pocock arrived at Martinique he assumed supreme command and immediately requested Rodney (who was then ill) to provide him with all available intelligence. Orders were also sent to Commodore Douglas to join him on 12 May off Cape St. Nicolas (Douglas, however, did not receive these messages until 3 May, and although he quickly despatched orders to collect his squadron this still took a number of days).[lxiii] As Rodney and Monckton were on bad terms at this stage of the occupation of Martinique, Pocock and Albemarle were required to significantly re-organize the landing force, including the purchase of slaves from Martinique and elsewhere (as it was realized that Jamaica was unlikely to provide any) – and about 600 slaves were thus obtained.[lxiv] Pocock further upset Rodney by taking charge of the latter’s flagship, Marlborough, and consigning his staff to a smaller 64, before departing.[lxv] Rodney subsequently penned an agitated series of letters outbound, including one to the Prime Minister.[lxvi]

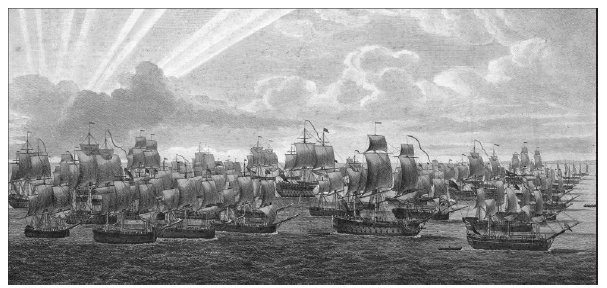

The Havana invasion force departing Martinique, 6 May 1762 (not showing frigates, sloops, transports, etc).

Commodore Augustus Keppel by Joshua Reynolds, 1749. Keppel, aboard HMS Valiant, was Pocock’s second in command.

Lt. General George Keppel, the Third Earl of Albermarle by Edward Fisher based on Joshua Reynolds, 1762

Pocock departed Martinique on 6 May and collected a trade convoy on its way to Jamaica, building the invasion fleet up to over 200 transports and 13 ships-of-the-line. The fleet arrived at Cape St. Nicolas on 17 May and collected what few of Commodore Douglas’ ships were in the area – the rest being still dispersed on blockade duties or re-victualing. The full squadron did not join Pocock until 25 May.[lxvii] Pocock’s complete force now consisted of 20 ship-of-the-line, a 50-gun cruiser, five frigates, three bomb vessels, a sloop, a cutter and the transports carrying 11,000 troops. Pocock allowed the merchants bound for Jamaica to depart (another indication of the powerful Port Royal merchant lobby’s influence) under the escort of HMS Centurion, with Commodore Douglas aboard.

Pocock, entrusted with a copy of Anson’s Spanish charts,[lxviii] and his own navigational experience from his time in the West Indies station, worked the invasion force around the dangerous north coast of Cuba, utilizing skilled navigators such as Captain Holmes in the sloop Bonetta and Captain Lindsay in the Trent, alongside the Lurcher to prepare the way. These vessels were in the process of scouting a route when they found Captain Elphinston of the Richmond on 29 May, who had completed his survey of the approach. A combination of sounding boats and coastal torch-fires to navigate allowed the fleet to sail through the Old Bahama Passage.[lxix]

Minor success occurred during this phase of the operation, such as on 2 June when Captain Alms in the Alarm captured the Spanish frigate Thetis and the storeship Phoenix.[lxx]

Havana force passing through the Old Strait of Bahama towards Havana, 2 June 1762

Map of Havana, showing location of Royal Navy operations: Pocock’s bombardment of the Chorea castle (left), the bombardment of the Morro fortress (centre) and Keppel and Albermarle’s landing (right); 1762.

Detailed map of the same from David Syrett’s Navy Records Society volume on the capture of Havana

Views of the harbour of Havana circa 1780, showing the harbour as entrance and exit.

El Morro Fortress overlooking the entrance to Havana harbour today.

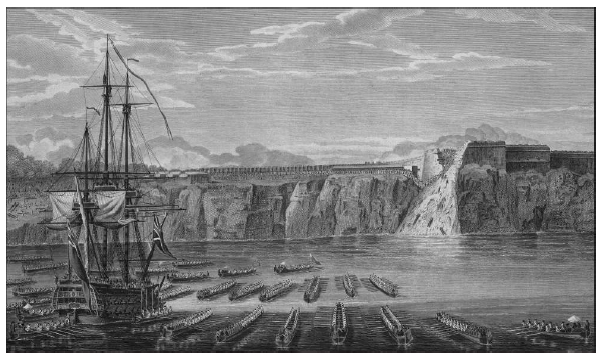

Keppel covers Albermarle’s landing on 7 June 1762, by Dominic Serres.

Pocock arrived off Havana on 6 June and started the landing the following day, with Commodore Keppel – in fact Albemarle’s brother – in overall command. 3,963 soldiers and grenadiers, artillerymen and so forth were landed by 10:30 am. The light Spanish defences at the Coximar river delta were swept away by Keppel’s naval gunfire.[lxxi] While Keppel was carrying out this phase of the operation with his six of the line, Pocock moved with his 13 of the line past the harbour – where he identified 12 Spanish warships – and farther to the west, conducting a feint landing with the Royal Marines at his disposal. Meanwhile the Earl of Albermarle landed his complete force between the Boca Noa and Coximar rivers, supported by gunfire from Captain Harvey in the Dragon along with the sloops Mercury and Bonetta. On 8 June Pocock despatched frigates to scout for additional landing locations and to conduct soundings along the coast, in the process discovering that the Spanish had now sunk a blockship at the harbour entrance, followed by a second on 9 June.[lxxii]

The total Spanish force garrisoning Havana’s various redoubt and fortress environs was 2,800 – three regiments of infantry and a regiment of dragoons – regulars, marines and sailors (the Spanish Admiral in charge of the fleet in Havana harbour was one Hevia), 5,000 militia, 250 arsenal hands, and 600 freed slaves.[lxxiii]

Pocock’s diversion bombardment of the Chorrera batteries, 11 June 1762

The remains of the Terreon de la Chorrera today

After securing his position ashore, Albermarle informed Pocock that he intended to attack the La Cabana heights above the Morro fortress on the 10th, and so Pocock provided a diversion in the form of Captain Knight in the Belleisle, which, along with Cerebus, Mercury, Lurcher and Bonetta bombarded the Chorrera (Terreon de la Chorrera – Cojimar) castle. On the 11th at 1 pm Colonel Carleton, Albermarle’s Quarter-Master General, led the assault on La Cabana and carried the heights successfully. Major General William Keppel, the third Keppel brother, was now appointed to command the El Morro siege operation.

To follow up this success, Pocock ordered three bomb vessels and the sloops Edgar, Stirling Castle and Echo to attack the town of Havana. On 12 June the Spanish sunk yet another blockship, completely blockading the entrance to the harbour.

Havana: landing artillery, 30 June 1762, by Dominic Serres, c. 1770-1775

Another view of the 30 June landing

On the 15th further landings were made, including 800 marines in two battalions, the first under Major Cambell and second under Major Collins. Another 1,200 troops were landed under Colonel Howe. A few days later mortars were landed from Thunder and Grenado, which began to bombard Morro on 20 June. Cannon were ashore and emplaced, adding their weight of shell to the attack.[lxxiv] In the meantime, Pocock tasked Keppel with deploying Dragon, Cambridge and Marlborough, together led by Captain Hervey, against the Morro, and their cannonade commenced on 1 July. The three ships suffered heavily from the fortress guns (of which there were 70), however, and were called off after six hours of shelling. Captain Goostrey of the Cambridge was killed.

For the remainder of July the Earl of Albermarle sieged the El Morro fortress – despite ever shortening supplies of water and ever increasing sick cases – but it wasn’t until 30 July that the exploding of a mine enabled the taking of the castle by assault, during which as many as 1,000 of the Spanish garrison were made casualties (130 killed, 27 wounded, 326 captured another 213 drowned while fleeing) and the Captain of the Morro fortress, Don Lewis de Velasco, was mortally wounded.[lxxv]

Dragon, Cambridge and Marlborough bombarding Morro Castle, Havana, 1 July 1762 by Richard Paton

Losses sustained during the shelling on 1 July.

Flatboats assault Morro Castle, 30 July 1762, by Dominic Serres. Alcide (64) shown.

Pocock for his part continued to carry out his theatre-level operation, constantly in touch with frigates carrying information about movements around Cuba and Florida, covering the Jamaica convoys, and watching for the approach of expected American reinforcements (who arrived 28 July – although reduced by 500 men who were captured in their transports by the Comte de Blenac’s detached flotilla) and simultaneously managing the supply situation of the siege itself.[lxxvi]

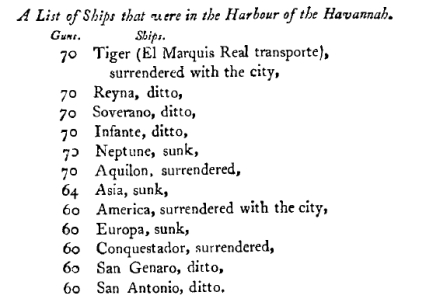

Havana was now surrounded, and the Spanish governor, Don Juan de Prado, asked for terms on 11 August, surrendering two days later. 12 warships were captured, eight line-of-battle ships being fit for sea (the other three being the sunk blockships), as well as £3 million in the process,[lxxvii] with Pocock and Albermarle split to the tune of 1/3 of the total treasure; Pocock’s take amounting to £123,000. Pocock handed out rewards as well, and the flagship’s purser, master and carpenter were respectively made the storekeeper, master attendant and master shipwright of Havana.[lxxviii]

British flatboats Entering Havana, 14 August 1762. (note sunken blockship at harbour entrance)

The British fleet entering Havana, with HMS Namur, Pocock’s flagship, flying his pendent as Admiral of the Blue, 21 August 1762. Commodore Keppel leads his squadron in HMS Valiant at the left. By Dominic Serres, 1775.

Capture of the Spanish fleet at Havana by Dominic Serres, 1768

Spanish ships captured at Havana.

The central plaza at Havana under British occupation following the successful siege, by Dominic Serres, c. 1765-70

The operation, however successful and profitable, had been costly, in particular in terms of sick cases resulting from the temperate climate and difficulty of the extended siege (560 army killed, 86 Royal Navy; and 4,708 army sick cases and 1,300 sailors).[lxxix] Anson, the architect of the plan, had died in London of a heart attack on 6 June, and thus never learned of the success of the campaign.[lxxx]

Pocock sailed for home but lost two ships and 12 transports as a result of stormy weather during the Atlantic crossing, reaching Spithead finally on 13 January 1763.

Pocock at 56 as Knight of the Bath, Admiral of the Blue, & C-in-C Havana, October (25 March) 1762

George Pocock as international celebrity: Chevalier de l’ordre du Bain, et Admiral de la flotte Britannique, fameux par les Explois sur les Mers des deux Indes

Legacy: An 18th Century Life

Pocock, now fabulously wealthy and internationally famous, purchased an estate at Mayfair, and, in 1764, bought the resplendent Orleans House at Twickenham. He married the widow Sophia Pitt Dent, together with whom he had a son, George (1765-1840; later the MP for Bridgwater and Baronet Pocock after 1821), and a daughter, Sophia (d. 1811), who married the Earl Powlet. Pocock retired in 1766 at the age of 60, returning to parliament where he notably voted against the repeal of the Stamp Act that February. Pocock, however, soon lost his seat in the 1768 election.[lxxxi] Pocock became master of Trinity House from 1786-1790, and was also vice-president of the Marine Society, his golden years noted for their public charity and serenity.

The Orleans House at Twickenham, painted by Joseph Nickolls c. 1750

The interior of the preserved Orleans House Gallery – the Octagon Room – as it stands today.

When Lally-Tollendal was captured – after the fall of Pondicherry – and sent to England, he pleaded that he might be introduced to Pocock, and, this request granted, is alleged to have spoken to the Admiral thus, “Dear Sir George, as the first man in your profession, I cannot but respect and esteem you, though you have been the greatest enemy I ever had. But for you, I should have triumphed in India, instead of being made a captive. When we first sailed out to give you battle, I had provided a number of musicians on board the Zodiaque, intending to give the ladies a ball upon our victory; but you left me only three fiddlers alive, and treated us all so roughly, that you quite spoiled us for dancing.”[lxxxii] Lally-Tollendal was traded back to France, where he was made a scapegoat for the failure in India, and executed at Paris on 9 May 1766.

Pocock outlived his erstwhile opponent of the East Indies, the Comte d’Ache, who died at Brest on 11 February 1780 at the age of 79.

Sir George Pocock, midshipman during the War of the Quadruple Alliance, commodore at the Leeward Islands during the War of Austrian Succession, master of the Indian Ocean and victor of Havana during the Seven Years War, Admiral of the Blue, died at Curzon Street, London, 3 April 1792 at the age of 86.

Sir George Pocock memorial at Westminster Abbey. Beneath Pocock’s coat of arms (two seahorses abreast a lion, topped by the crest of an antelope issuing from a naval crown, with motto, “Faithful to the King and Kingdom”), sits a majestic Britannia, confidently grasping a thunderbolt, her left arm resting on a profile showing Pocock’s distinctive Mona Lisa smile. Commissioned by George Pocock, esquire, and sculpted by John Bacon in 1796. Sir George is buried at St. Mary’s Church, Twickenham.

Notes

[i] James Stanier Clarke and John McArthur, eds., The Naval Chronicle, Volume VIII, 2010th ed. (Cambridge University Press, 1802)., p. 442

[ii] Tom Pocock, “Pocock, Sir George (1706-1792),” The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004).

[iii] John D. Grainger, Dictionary of British Naval Battles (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2016)., p. 104

[iv] Pocock, “Pocock, Sir George (1706-1792).”

[v] List of Royal Navy Post Captains, 1714-1830, Navy Records Society online.

[vi] J. J. Colledge and Ben Warlow, Ships of the Royal Navy, The Complete Record of All Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Philadelphia & Newbury: Casemate, 2010)., p. 10

[vii] Clarke and McArthur, The Naval Chronicle, Volume VIII., p. 442

[viii] Colledge and Warlow, Ships of the Royal Navy, The Complete Record of All Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy., p. 390

[ix] Brian Lavery, The Arming and Fitting of English Ships of War, 1600-1815 (London: Conway Maritime Press, Ltd., 1998)., p. 119

[x] N. A. M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2006)., p. 412; Robert Gardiner and Brian Lavery, eds., The Line of Battle: The Sailing Warship 1650-1840, Conway’s History of the Ship (London: Conway Maritime Press, 2004)., p. 19

[xi] Richard F. Simpson, “The Naval Career of Admiral Sir George Pocock, K. B., 1743-1763” (Indiana University, 1950)., p.2

[xii] Richard Harding, “Legge, Edward (1710-1747),” The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004).

[xiii] Herbert Richmond, The Navy In The War of 1739-48, vol. 3, 3 vols. (Cambridge University Press, 1920)., p. 70

[xiv] Clarke and McArthur, The Naval Chronicle, Volume VIII., p. 443

[xv] Grainger, Dictionary of British Naval Battles., p. 103; see also Hawke to Corbett, 17 October 1747, in Ruddock Mackay, ed., The Hawke Papers, A Selection: 1743 – 1771, Navy Records Society 129 (Aldershot, Hants: Scolar Press, 1990)., p. 51-55

[xvi] Richmond, The Navy In The War of 1739-48., p. 72

[xvii] Clarke and McArthur, The Naval Chronicle, Volume VIII., p. 443; Martin Robson, A History of the Royal Navy: The Seven Years War (London: I. B. Tauris & Co. Ltd., 2016)., loc. 1272

[xviii] Robson, A History of the Royal Navy: The Seven Years War., loc. 1300

[xix] Robson., loc. 1300

[xx] Robson., loc. 1323

[xxi] Pocock, “Pocock, Sir George (1706-1792).” Robson, A History of the Royal Navy: The Seven Years War., loc. 1341

[xxii] A. T. Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660 – 1783 (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1987)., p. 306

[xxiii] Rodger, The Command of the Ocean., p. 275

[xxiv] William Laird Clowes, The Royal Navy, A History From the Earliest Times to the Present, vol. 3, 5 vols. (London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company, 1898)., p. 565

[xxv] Robson, A History of the Royal Navy: The Seven Years War., loc. 1347

[xxvi] Jonathan R. Dull, The French Navy and the Seven Years’ War (University of Nebraska: Thomson-Shore, Inc., 2005)., loc. 1847

[xxvii] Robson, A History of the Royal Navy: The Seven Years War., loc. 1368

[xxviii] Clarke and McArthur, The Naval Chronicle, Volume VIII., p. 445

[xxix] Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660 – 1783., p. 307

[xxx] Clarke and McArthur, The Naval Chronicle, Volume VIII., p. 446

[xxxi] Dull, The French Navy and the Seven Years’ War., loc. 1847

[xxxii] Robson, A History of the Royal Navy: The Seven Years War., loc. 1401

[xxxiii] Dull, The French Navy and the Seven Years’ War., loc. 1847

[xxxiv] Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660 – 1783., p. 308

[xxxv] Clarke and McArthur, The Naval Chronicle, Volume VIII., p. 446

[xxxvi] N. A. M. Rodger, The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy (London: Fontana Press, 1988)., p. 247

[xxxvii] Clarke and McArthur, The Naval Chronicle, Volume VIII., p. 447

[xxxviii] Clarke and McArthur., p. 448

[xxxix] Clarke and McArthur., p. 449

[xl] Robson, A History of the Royal Navy: The Seven Years War., loc. 1401

[xli] Clowes, The Royal Navy, A History From the Earliest Times to the Present., p. 181

[xlii] Sam Willis, Fighting at Sea in the Eighteenth Century: The Art of Sailing Warfare (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2008)., p. 206

[xliii] Dull, The French Navy and the Seven Years’ War., loc. 1839

[xliv] Clowes, The Royal Navy, A History From the Earliest Times to the Present., p. 181

[xlv] Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660 – 1783., p. 310

[xlvi] Julian Corbett, The Seven Years War, A Study in British Combined Strategy (London: The Folio Society, 2001)., p. 452-3

[xlvii] Clarke and McArthur, The Naval Chronicle, Volume VIII., p. 451

[xlviii] Willis, Fighting at Sea in the Eighteenth Century: The Art of Sailing Warfare., p. 207

[xlix] Clarke and McArthur, The Naval Chronicle, Volume VIII., p. 451-4

[l] Rodger, The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy., p. 337

[li] Rodger., p. 289

[lii] Corbett, The Seven Years War, A Study in British Combined Strategy., p. 456-7

[liii] John Malcolm, Robert, Lord Clive: Collected from the Family Papers Communicated by the Earl of Powis, Kindle, vol. 1, 3 vols. (London: John Murray, 1836).

[liv] Corbett, The Seven Years War, A Study in British Combined Strategy., p. 461-2

[lv] Lawrence James, Raj: The Making and Unmaking of British India (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1997)., p. 43

[lvi] Rodger, The Command of the Ocean., p. 285

[lvii] Corbett, The Seven Years War, A Study in British Combined Strategy., p. 546

[lviii] David Syrett, The Siege and Capture of Havana, 1762 (London: Spottiswoode, Ballantyne and Co. Ltd., 1970)., p. xv, also #64 Albemarle to Egremont, Portsmouth, 22 February, p. 51

[lix] Syrett., p. xiv

[lx] Syrett., p. xiv

[lxi] Alexander Howlett, “Captain Charles Middleton and the Seven Years’ War,” Canadian War Studies Association (blog), December 31, 2016, https://cawarstudies.wordpress.com/2016/12/31/captain-charles-middleton-and-the-seven-years-war/.

[lxii] Syrett, The Siege and Capture of Havana, 1762., p. xvi-xvii

[lxiii] Syrett., #143, Pocock to Douglas, 26 April, p. 98-9

[lxiv] Syrett., p. xvi-xviii

[lxv] Corbett, The Seven Years War, A Study in British Combined Strategy., p. 553; see also David Syrett, ed., The Rodney Papers, Volume I, 1742 – 1763, vol. 1, Navy Records Society 148 (Aldershot, Hants: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2005)., #876, Rodney to Clevland, 27 May 1762, p. 452-3

[lxvi] Syrett, The Rodney Papers, Volume I, 1742 – 1763., #879, Rodney to Newcastle, 1 June 1762, p. 456-7

[lxvii] Syrett, The Siege and Capture of Havana, 1762., p. xix

[lxviii] Andrew Lambert, Admirals (London: Faber and Faber Limited, 2009)., p. 153

[lxix] Clarke and McArthur, The Naval Chronicle, Volume VIII., p. 456

[lxx] Clarke and McArthur., p. 456

[lxxi] Syrett, The Siege and Capture of Havana, 1762., p. xxiii

[lxxii] Clarke and McArthur, The Naval Chronicle, Volume VIII., p. 457

[lxxiii] Corbett, The Seven Years War, A Study in British Combined Strategy., p. 562 fn

[lxxiv] Clarke and McArthur, The Naval Chronicle, Volume VIII., p. 458

[lxxv] Pocock, “Pocock, Sir George (1706-1792).”; Clarke and McArthur, The Naval Chronicle, Volume VIII., p. 460

[lxxvi] Corbett, The Seven Years War, A Study in British Combined Strategy., p. 566-9

[lxxvii] Grainger, Dictionary of British Naval Battles., p. 222

[lxxviii] Rodger, The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy., p. 287

[lxxix] Herbert Richmond, Statesmen and Sea Power (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1946).

[lxxx] N. A. M. Rodger, “Anson, George, Baron Anson (1697-1762),” The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004).

[lxxxi] Pocock, “Pocock, Sir George (1706-1792).”

[lxxxii] George Godfrey Cunningham, A History of England in the Lives of Englishmen, vol. 5 (London: A. Fullarton and Co., 1853)., p. 412