Any Other Name

The Origin of HMS Dreadnought (SSN, S101)

Crest of S101.[i]

Dreadnought was the Royal Navy’s first nuclear powered attack submarine (SSN). Dreadnought was built through the joint efforts of the Chief of the Defence Staff, Admiral of the Fleet, Louis Mountbatten in tandem with the Chief of the US Navy’s Nuclear Power Division & Director of the Naval Reactor Branch at the Bureau of Ships, Vice-Admiral Hyman G. Rickover. How did the Royal Navy develop a nuclear submarine force, and why was the distinctive name of Dreadnought chosen for the first SSN produced in Britain?

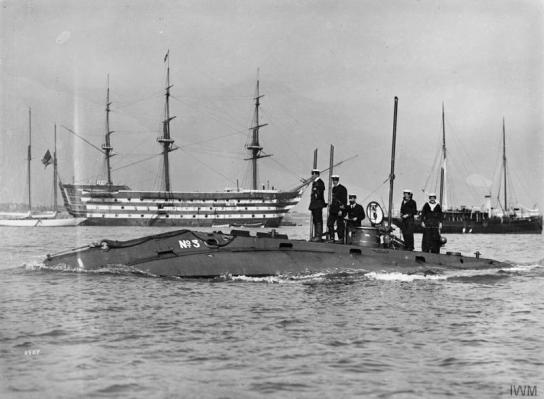

HMS Victory and HM Submarine No. 3 of 5 Holland boats, probably 1903.[ii]

Background

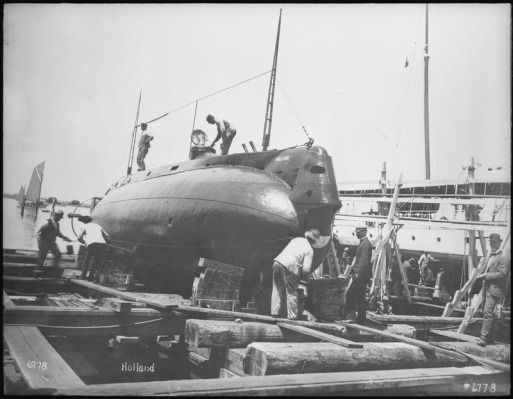

The submarine as an element of industrial warfare developed first during the American Civil War. The Confederate submarine H. L. Hunley infamously attacked and sank USS Housitonic, on 17 February 1864.[iii] Thirty-six years later, pioneering naval designer John P. Holland had successfully coupled the Whitehead self-propelled torpedo to a petrol-electric submarine platform. The United States Navy purchased Holland’s design and commissioned Holland as SS 1.

The Royal Navy’s first operational submarines were, likewise, Holland boats, acquired as a component of First Sea Lord John Fisher’s flotilla defence doctrine.[iv] Fisher planned to purchase 12 submarines starting in 1904.[v] Fisher, the motive force behind the first HMS Dreadnought (1905) was typically not kidding around and by the end of 1904, £770,050 had been spent on submarines, considerably more than the previous years estimate.[vi]

USS Holland, under construction 1900.[vii]

The First and Second World War demonstrated that the submarine was an essential naval system, both for blockade defense and for attacking enemy warships and supply-lines.[viii] Submarines influenced naval deployments in both World Wars (North Sea & Atlantic, 1917 and 1943;[ix] Pacific, 1945). The growing importance of the submarine was now matched by the deepening uncertainty of the role for the traditional surface fleet in the Atomic age.

In 1947 the Royal Navy’s Naval Review was concerned by the implications of atomic bombs for the future of the Navy, and indeed the existence of British society altogether: “Is it morally defensible or even worth while to mortgage our souls and all that makes life worth living for an existence devoted to an end that at best is unlikely to offer anything better than mere survival in a Wellsian aftermath of devastation, where the most ardent optimist could hardly hope to distinguish victor from vanquished?”[x] Stephen Roskill, also the Royal Navy’s official historian for the Second World War, witnessed the Crossroads test events and became enraptured by the destructive power of the atomic weapons. In particular, he observed the danger of nuclear attack against a fleet in port.[xi]

Following the Second World War, budget imperatives pushed the submarine to the fore on acquisition.[xii] Britain’s post-war political and industrial decline required the economy of effort that the submarine represented.[xiii] There was also speculation by futurists that submarines armed with nuclear equipped missiles, rather than RAF bombers or land-based ICBMs, would become the ultimate strategic deterrent. The introduction of the atomic bomb strengthened the necessity for the submarine’s role within the RN: Submarines, especially if nuclear powered and equipped, could be discreetly stationed at bases around the globe, minimizing the risk of attack on the homeland.

Admiral Rickover inspects Nautilus, 1954[xiv]

The New Battlecruisers; USN Nuclear Attack Submarines

The nuclear submarine program in the United States was overseen by USN Captain and later Vice-Admiral, Hyman Rickover. A graduate of Annapolis, with years of service aboard submarines, Rickover was the USN’s appointee to oversee the electrical section of the Navy’s Bureau of Ships. Rickover brought a reputation for ruthless centralization and attention to detail: Lt. Jimmy Carter recalled the sharp-end of Rickover’s focus.[xv] Rickover’s objective as Director of the Naval Reactor Branch of the USN’s Bureau of Ships, after the Second World War, was to harness nuclear power for submarines. He achieved this goal with the development of USS Nautilus (SSN-571), launched in 1954. Nautilus’ first generation Westinghouse reactor (STR, followed by S2W) provided the submarine with 13,400 horsepower, and 900 hours endurance at full power.[xvi] Nautilus was joined by USS Seawolf (SSN-575) in March 1957, leading to the production run of four Skate class SSNs, the last of which, USS Seadragon (SSN-584) was commissioned in December 1959.[xvii]

Nautilus approaches Manhattan.[xviii]

In August 1958 USS Nautilus accompanied by USS Skate (SSN-578) crossed the Arctic via the North Pole.[xix] Dr. Alfred McLaren, an influential Arctic scientist and explorer described the details of this mission.[xx] Nautilus’ first nuclear core proved capable of 60,000 miles of cruising endurance and its third core was designed for 130,000 miles.[xxi] Next in accomplishment, the $109 million dual nuclear reactor, USS Triton (SSRN) circumnavigated the globe in 84 days.[xxii] In 1959 USS Skipjack, designed with a teardrop hull-form and sporting the new S5W reactor became the fastest submarine in the USN. USS Halibut (SSGN-587), introduced in 1959, experimented with launching Regulus generation missiles. These were impressive nautical and maritime feats in and of themselves, not significantly less complicated than NASA’s simultaneous Project Mercury.

These early generation nuclear submarines were, however, three or four times more expensive to operate respective to their conventional electric submarine counterparts. During a year-long overhaul, Nautilus required over $10 million in repairs.[xxiii] Nevertheless, C. W. M., writing for the RN’s Naval Review, considered the transition to nuclear as significant a revolution in military affairs as the sail-steam transition.[xxiv]

First Sea Lord Louis Mountbatten, Admiral of the Fleet, as of October 1956.[xxv]

Mountbatten’s background

The Royal Navy’s nuclear submarine force was in large part the product of First Sea Lord Louis Mountbatten and Rickover’s cooperation on nuclear technology.[xxvi] Mountbatten was a great-grandson of Queen Victoria. He was the brother of Princess Alice (mother of Queen Elizabeth II’s consort, Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh).[xxvii] Mountbatten’s father, Louis of Battenberg, had been no less than the XO of HMS Dreadnought (1905)- the battleship of Sir John Fisher’s imagining.[xxviii] After a stint as the Director of Naval Intelligence and Second Sea Lord, by December 1912, Battenberg became First Sea Lord. Winston Churchill was the Admiralty First Lord.[xxix] Battenberg’s son, Louis Mountbatten, after an important career in the Second World War, including Supreme Commander South-East Asia, became First Sea Lord in April 1955.[xxx] Winston Churchill, Battenberg’s old master and once again PM (1951-55) had blocked Mountbatten’s appointment until Churchill resigned in 1955.

Happier times: Churchill and Prince Battenberg.[xxxi]

The significance of the new nuclear powered submarines as the future capital ships appealed to Mountbatten’s technocratic sympathies.[xxxii] In a November 1955 meeting with Admiral and Chief of Naval Operations Arleigh Burke (USN) Mountbatten learned about the American Navy’s future prospects for launching nuclear tipped missiles from submarines; what became the Polaris program.[xxxiii]

In terms of nuclear strategy, Mountbatten was considered a proponent of the emerging limited war, or flexible response doctrine, later expressed by US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara in his June 1962 Ann Arbour speech.[xxxiv] Mountbatten was trying to maintain a balanced RN, capable of carrier, amphibious and submarine operations.[xxxv] However, the introduction of thermonuclear weapons served only to reiterate the conclusions drawn post-war: the fleet had to disperse as much as possible to survive.

Mountbatten visited the United States in October 1955 in an attempt to gather information on the USN’s nuclear submarine program. His first encounters with Rickover’s school were frosty: Rickover blocked Mountbatten’s planned tour of Nautilus.[xxxvi] Rickover argued that the USA-UK Agreement on Military Atomic Co-operation did not yet “extend so far.”[xxxvii] Rickover actually met Mountbatten in London in August 1956, and it has been argued that Mountbatten then won-over the Strangelovian Admiral.[xxxviii] Rickover and Mountbatten worked in tandem for the next two years to surmount the diplomatic and legal hurdles required to enable transfer of the nuclear reactor technology. In December 1957 Rickover again visited Britain and met with Mountbatten, together they stressed the need for rapid movement on the reactor technology transfer.[xxxix] The US Atomic Energy Act was amended after March 1958 to enable Britain to acquire the legal right to possess the Westinghouse reactor technology. Nuclear fuel would be provided by the US.[xl]

Sandys in December 1947, MP.[xli]

The necessity for the Royal Navy’s first nuclear attack submarine

Why the focus on submarines? In 1957 Harold Macmillan, Winston Churchill’s former Minister of Defence, and then Foreign Secretary under PM Anthony Eden,[xlii] became the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and implemented a Defence review chaired by Minister of Defence Duncan Sandys. Sandys, Churchill’s son-in-law, issued his report in April 1957. The Sandys’ white paper “placed great reliance on nuclear weapons (the British thermonuclear weapon was about to be tested); and contained the ominous words ‘the role of naval forces in total war is uncertain’”.[xliii] Sandys’ recommendations included the termination of military conscription.[xliv] Existing aircraft carriers would transition to primarily anti-submarine platforms.[xlv] Sandys was reacting to the new public perceptions surrounding the thermonuclear bomb.[xlvi] The expectation was that the Navy would only be able to play a role in a limited war, and then primarily as a component of NATO’s anti-submarine warfare campaign in the North Sea and Atlantic.[xlvii] Nevertheless, part of the new Defence policy was a refocus on the RN as an element of British culture. The “naming policy” towards nuclear powered submarines reflected this.[xlviii] The new focus on nuclear submarines spoke to Mountbatten’s pragmatism: the RAF – RN rivalry over the Fleet Air Arm had not gone in the Navy’s favour.[xlix] The submarine was the RN’s last ace. Thus, the Dreadnought Project Team, with assistant director Naval Construction Rowland Baker as chief, was assembled in October 1957.[l]

In 1957 Rickover visited London and impressed upon the Admiralty the desirability of speedily adopting the American technology.[li] Initial controversy had been caused when Rickover had shown preference for Rolls Royce as the primary contractor, a decision that alienated Vickers (Rolls Royce did not yet have permission from the UK Atomic Energy Authority to produce fuel rods).[lii] At any rate, the US government contractor was indeed Westinghouse.[liii]

Mountbatten, in an effort to generate support for the RN SSN program, invited Sandys to tour Nautilus during its visit to Portland.[liv] Sandys was impressed, and Mountbatten now became concerned that the Defence Ministry would “decide that the nuclear-propelled submarine … made our present Navy completely obsolete.”[lv]

Mountbatten’s promotion had been approved by 22 May 1958 to Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS), and so Admiral of the Fleet Charles Lambe became First Sea Lord (and Chief of the Naval Staff) in December 1958.[lvi] Lambe supported Mountbatten. The CDS now felt that with Rickover’s cooperation, he was in a position to advance his reforms. Rickover had to be kept onside but without turning the entire project over to the Americans: for example, Rickover was insistent that he “personally select all the senior personnel for Dreadnought” an opinion Mountbatten torpedoed after he demonstrated his own hands-on approach and knowledge of engineering during a visit to USS Skipjack in October 1958.[lvii]

Britain’s submarine for the “jet age”.[lviii]

Technical specifications of HMS Dreadnought

The name of Britain’s first nuclear attack submarine was chosen to reflect the technological prowess of Britain during the Edwardian years, and to convey the ascension of the submarine to the position of capital ship.[lix] Battlecruiser names were chosen as it was expected that the submarines would fulfill much of the battlecruisers’ old role in terms of the “control [of] sea communications”.[lx] Subsequent submarines, Valiant (S102) and Warspite (S103) were named for the Queen Elizabeth class battleships familiar to the 5th Battle Squadron of the Battle Cruiser Fleet.

Dreadnought was laid down on 12 June 1959 at Vickers (Barrow), and launched on Trafalgar Day (October 21) 1960 by Queen Elizabeth II and members of the royal family. The SSN was commissioned on 17 April 1963. Dreadnought was 265.8 feet in length by 32.3 feet breadth, dimensions not indifferent to a German Type IX submarine of 1940 (261 feet by 22.4 feet),[lxi] although displacing almost three times as much, 3,000 tons on the surface and 3,500-4,000 tons submerged, and capable of diving to over 1000 ft. The submarine was armed with six torpedo tubes for 21-inch torpedoes. [lxii] 88 officers and men controlled the SSN.[lxiii] Dreadnought’s reactor was a fifth generation submarine reactor produced by Westinghouse (S5W) known for its redundancy and reliability.[lxiv] The reactor could develop 15,000 horsepower and remain at full power (28 knots) for at least 5,500 hours.[lxv]

S.101 enroute to sink the German derelict tanker Essberger Chemist with HMS Llandaff, F61, in background. See the video of the sinking in the endnotes.[lxvi]

Conclusion

By 1960 it was stated in the Naval Review that nuclear propulsion was “an essential characteristic” in submarine design.[lxxi] In 1962 Skybolt, the USAF nuclear attack system the RAF had hoped to acquire was about to be canceled.[lxxii] The result was a conciliation agreement between JFK and Harold Macmillan: the RN now planned to transition to the Submarine Launched Ballistic Missile system, Polaris. Mountbatten, as we’ve seen, had encountered Polaris before, between 1955 and 1958.[lxxiii]

Operating Polaris would be the four SSBNs of the Resolution class, although these larger warships would require first a proven nuclear attack submarine platform.[lxxiv] The Navy’s aircraft carriers were in need of replacement, although this option was considered prohibitively expensive according to the Naval Staff. The 1964 Labour government’s Defence review invariably put the focus on affordability.[lxxv]

As the Dreadnought Project Team went about their work, advances in submarine warfare further emphasized the future role of the submarine: the Admiralty’s Underwater Weapons Establishment at Portland had devised a new generation of passive and active sonar for HMS Dreadnought.[lxvii] The advanced sonar and torpedo technologies of the 1960s made the submarine itself an anti-submarine weapon.[lxviii] As a result of the technology transfer protocol, the RN’s next class of nuclear powered submarines, the Valiant class, employed Rolls Royce Pressurized Water Reactors (PWR1).[lxix] Valiant was finally commissioned in July 1966.[lxx]

The SSN and SSBNs represented the last visceral image of Britain as a great power.[lxxvi] In 1966 the failure of the CVA 01 program and the climax of the struggle with the RAF for control of the Fleet Air Arm resulted in the submarines unexpected triumph.[lxxvii]

Dreadnought was the first RN submarine to surface at the North Pole on 3 March 1971, not long after the conclusion of the Apollo 14 mission on 6 February.[lxxviii] Dreadnought was decommissioned in 1980, having served a longer career than its namesake predecessor. The remains of Dreadnought, along with Britain’s other decommissioned nuclear submarines, are currently laid up for disposal at Rosyth, the former base of the Battle Cruiser Fleet during the First World War.

Rosyth dockyard showing decommissioned SSNs and SSBNs.[lxxix]

Retired USN nuclear attack submarines in 1993.[lxxx]

[i]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Dreadnought_%28S101%29#mediaviewer/File:Dreadnought_crest.gif

[ii] http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205024652

[iii]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Housatonic_%281861%29#Sunk_in_the_first_submarine_attack http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sinking_of_USS_Housatonic

[iv] Jon Tetsuro Sumida, In Defence of Naval Supremacy: Finance, Technology , and British Naval Policy, 1889-1914, 1993rd ed. (Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1989)., Table 10, “Expenditures on Flotilla Construciton by Type, 1889-90 to 1913-14 (not including cost of armament)., p. 352

[v] Nicholas Lambert, Sir John Fisher’s Naval Revolution (Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 2002)., p. 117

[vi] Sumida, In Defence of Naval Supremacy: Finance, Technology , and British Naval Policy, 1889-1914., Table 10, “Expenditures on Flotilla Construciton by Type, 1889-90 to 1913-14 (not including cost of armament)., p. 352

[vii] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Holland_(SS-1)#mediaviewer/File:Holland_(SSl)._Starboard_bow,_on_ways,_1900_-_NARA_-_512954.tif

[viii] Herman Kahn, On Thermonuclear War, 2nd ed. (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1961). p. 354-6

[ix] Duncan Redford, “The March 1943 Crisis in the Battle of the Atlantic: Myth and Reality,” History 92, no. 305 (January 1, 2007): 64. Redford is critical of both US (Samuel E. Morrison) and British (Stephen W. Roskill) official historians for over-stating the significance of the 1943 submarine crisis. Apparently Morrison had received the crucial documents from Roskill.

[x] Guy Liardet, “Nuclear Matters,” in Dreadnought to Daring: 100 Years of Comment, Controversy and Debate in The Naval Review, ed. Peter Horne (Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Seaforth Publishing, 2012), 373–89. p. 376; quoting, Mate, “Second Thoughts on Atomic Warfare,” Naval Review 35, no. 2 (1947): 131–33.

[xi] SWR, “Bases and the Bomb. Some Implications of ‘Operation Crossroads.,’” Naval Review 35, no. 1 (January 1947): 16–24. p. 17; Stephen Roskill had been appointed a high level of clearance to report on the Crossroads operations, see Barry Gough, Historical Dreadnoughts: Arthur Marder, Stephen Roskill and Battle for Naval History (Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Seaforth Publishing, 2010). p. 62. Roskill and his team saw the air-dropped “Able” detonation on 1 July 1946 aboard USN Auxiliary Blue Ridge. Roskill also saw the submarine style detonation of “Baker” on 26 July.

[xii] Duncan Redford, “The ‘Hallmark of a First-Class Navy’: The Nuclear Powered Submarine in the Royal Navy 1960-77,” Contemporary British History 23, no. 2 (June 2, 2009): 181–97. p. 182

[xiii] Ibid. p. 183-4

[xiv] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hyman_Rickover_inspecting_USS_Nautilus.jpg

[xv] Jed Graham, “Rickover Was Way Up On Subs: Full Steam Ahead: The Admiral Made Sure to the U.S. Navy Its Nuclear Edge,” Investor’s Business Daily, May 1, 2007, online edition, sec. Leaders & Success.

[xvi] Wikimedia Foundation, “S2W Reactor,” En.wikipedia.org, November 20, 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/S2W_reactor.; Big Book of Warfare, “U.S. Naval Reactors,” Alternatewars.com, April 24, 2011, http://www.alternatewars.com/BBOW/Nuclear/US_Naval_Reactors.htm.

[xvii] davidvblack, “The Dawn of the Nuclear Age, Interview with Nuclear Engineer S. Reed Nixon,” blog, The Elements Unearthed, (December 28, 2010), http://elementsunearthed.com/2010/12/28/the-dawn-of-the-nuclear-age/., see also “USS Seadragon (SSN-584),” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, November 24, 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=USS_Seadragon_(SSN-584)&oldid=631398860.

[xviii] http://vicsocotra.com/2010_stories/1-6-10-pulling-trigger2.jpg

[xix] Society for Science & the Public, “Two U.S. Atomic Subs Sail under North Pole.,” The Science News-Letter 74, no. 8 (115AD): 23 August 1958.

[xx] William Broad, “Scientists at Work — Alfred McLaren; Explorer of Arctic Depths Plans Another Trip North,” The New York Times, October 29, 2002, online edition, sec. Science.; Alfred S. McLaren, “Analysis of the Under-Ice Topography in the Arctic Basin as Recorded by the USS Nautilus during August 1958,” Arctic Institute of North America 41, no. 2 (June 1988): 117–26.

[xxi] Kahn, On Thermonuclear War. p. 265

[xxii] Ian Hillbeck, “Submarines Association, Boat Database, Dreadnought S101,” Database, Barrow Submarines Association, (1997), http://www.rnsubs.co.uk/Boats/BoatDB2/index.php?BoatID=680.

[xxiii] Kahn, On Thermonuclear War. p. 265

[xxiv] C. W. M., “Marine Nuclear Propulsion in Great Britain,” The Naval Review 48, no. 4 (1960): 393. p. 393

[xxv] http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205125298, “Mountbatten, Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas, First Earl Mountbatten of Burma,” The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/31480.

[xxvi] J. R. Hill, “The Realities of Medium Power, 1946 to the Present,” in The Oxford Illustrated History of the Royal Navy, ed. J. R. Hill and Bryan Ranft (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 381–408. p. 384

[xxvii] Mountbatten, thepeerage.com http://www.thepeerage.com/p10075.htm#i100750

[xxviii] Philip Ziegler, Mountbatten: A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1985)., p. 23

[xxix] Ibid., p. 30-1

[xxx] “Mountbatten, Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas, First Earl Mountbatten of Burma.”

[xxxi] Jim_and_Gerry, “Churchill – Less Than Audacious,” First World War Hidden History, accessed November 28, 2014, https://firstworldwarhiddenhistory.wordpress.com/2014/10/22/churchill-less-than-audacious/.

[xxxii] Eric Grove, The Royal Navy since 1815 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005)., p. 231

[xxxiii] Ziegler, Mountbatten: A Biography. p. 560, see also, Eric Grove, Vanguard to Trident (Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institue, 1987). p. 234

[xxxiv] Fred Kaplan, The Wizards of Armageddon (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1983)., p. 316. See also: Herman Kahn, On Thermonuclear War., an abridged version of “No Cities” speech can be seen here: Robert McNamara, “‘No Cities’ Speech by Sec. of Defense McNamara, 1962,” June 1962, http://www.radiochemistry.org/speech_archives/text/04_mcnamara.shtml. J. R. Hill and Bryan Ranft, eds., The Oxford Illustrated History of the Royal Navy (Frome, Somerset: Oxford University Press, 1995). p. 386. US President John F. Kennedy and UK Prime Minister Harold Macmillan had agreed at the Nassau summit in November 1962, shortly after the Cuban Missile Crisis. See also Lawrence Freedman, “The First Two Generations of Nuclear Strategists,” in Makers of Modern Strategy: From Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age, ed. Peter Paret (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1986), 735–78., & Michael Carver, “Conventional Warfare in the Nuclear Age,” in Makers of Modern Strategy: From Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age, ed. Peter Paret (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1986), 779–814.

[xxxv] Hill, “The Realities of Medium Power, 1946 to the Present.” p. 386

[xxxvi] Ziegler, Mountbatten: A Biography., p. 558

[xxxvii] Ibid., p. 558

[xxxviii] Ibid., p. 558

[xxxix] Ibid., p. 558-9

[xl] Grove, Vanguard to Trident. p. 232

[xli] http://www.cvce.eu/en/obj/duncan_sandys-en-ddf753fe-5b95-4f0e-95a4-2172c8f4b623.html

[xlii] Grove, The Royal Navy since 1815. p. 224

[xliii] Hill, “The Realities of Medium Power, 1946 to the Present.” p. 386

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conscription_in_the_United_Kingdom#cite_note-3 [xliv]

[xlv] Grove, The Royal Navy since 1815. p. 228-30.

[xlvi] Peter Nailor, “The Development of the Royal Navy since 1945,” in The Future of British Sea Power, ed. Geoffrey Till, Camelot Press Ltd (Southhampton: Naval Institute Press, 1984), 13–23. p. 15

[xlvii] Grove, Vanguard to Trident. p. 203

[xlviii] Redford, “The ‘Hallmark of a First-Class Navy’: The Nuclear Powered Submarine in the Royal Navy 1960-77.” p. 182

[xlix] Ibid. p. 189

[l] Grove, Vanguard to Trident. p. 232

[li] Ibid. p. 232

[lii] Ibid., p. 232

[liii] Ibid. p. 232

[liv] Ibid. p. 232

[lv] Ziegler, Mountbatten: A Biography. p. 560

[lvi] Ibid. p. 564-5

[lvii] Ibid. p. 559

[lviii] http://forummarine.forumactif.com/t5047-sous-marin-nucleaire-d-attaque-hms-dreadnought ; Redford, “The ‘Hallmark of a First-Class Navy’: The Nuclear Powered Submarine in the Royal Navy 1960-77.” , p. 186

[lix] Ibid. p. 186

[lx] Ibid. p. 186

[lxi] “German Type IX Submarine,” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, November 27, 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=German_Type_IX_submarine&oldid=634188836., Tony Gibbons, ed., The Encyclopedia of Ships: Over 1,500 Military and Civilian Ships from 5000 B.C. to Teh Present Day (San Diego: Thunder Bay Press, 2001). p. 414

[lxii] J. J. Colledge and Ben Warlow, Ships of the Royal Navy, The Complete Record of All Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Philadelphia & Newbury: Casemate, 2010). ebook

[lxiii] Hillbeck, “Submarines Association, Boat Database, Dreadnought S101.”

[lxiv] Wikimedia Foundation, “S5W Reactor,” En.wikipedia.org, May 30, 2013, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/S5W_reactor.

[lxv] Gibbons, The Encyclopedia of Ships: Over 1,500 Military and Civilian Ships from 5000 B.C. to Teh Present Day. p. 454-5

[lxvi] https://www.flickr.com/photos/alec_blyth/5617490536/sizes/l ; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O7lTKO3pdCY

[lxvii] Grove, Vanguard to Trident. p. 233

[lxviii] Redford, “The ‘Hallmark of a First-Class Navy’: The Nuclear Powered Submarine in the Royal Navy 1960-77.”, p. 183-4

[lxix] Duncan Redford and Philip. D. Grove, The Royal Navy, A History Since 1900, A History of the Royal Navy Series 14 (New York: I. B. Tauris, 2014)., p. 244

[lxx] Grove, Vanguard to Trident. p. 233

[lxxi] M., “Marine Nuclear Propulsion in Great Britain.” p. 393

[lxxii] Hill, “The Realities of Medium Power, 1946 to the Present.” p. 386

[lxxiii] Ibid. p. 386; Ziegler, Mountbatten: A Biography. p. 560

[lxxiv] Hill, “The Realities of Medium Power, 1946 to the Present.” p. 386

[lxxv] Ibid. p. 386

[lxxvi] Redford, “The ‘Hallmark of a First-Class Navy’: The Nuclear Powered Submarine in the Royal Navy 1960-77.” p. 189

[lxxvii] Ibid. p. 193

[lxxviii] Wikimedia Foundation, “List of Apollo Missions,” En.wikipedia.org, November 6, 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Apollo_missions.

[lxxix] http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-Km9V-_YBdGc/Th7tL5yKMqI/AAAAAAAAAlU/ERLxbzTSGMM/s1600/rosyth.JPG

[lxxx] http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b2/USS_Sperry_(AS-12)_and_retired_submarines_at_Puget_Sound_1993.JPEG

Pingback: Royal Navy On This Day 12 June ….. | Nick Of Time Marketing UK