After Trafalgar: The Royal Navy & the Napoleonic Wars, 1806 – 1816

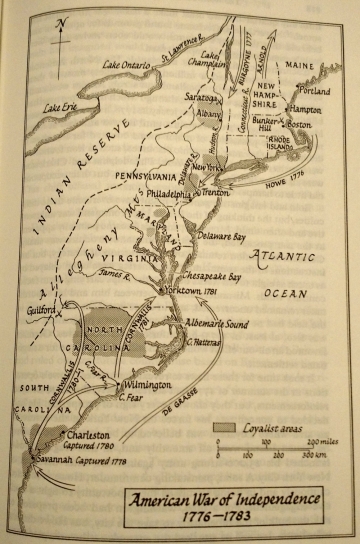

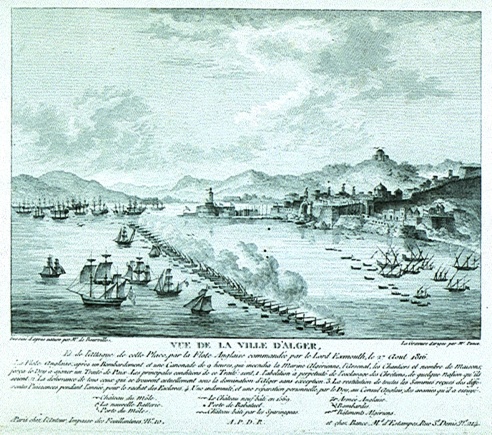

This article examines the operational history of the Royal Navy during the military and geopolitical progress of the Napoleonic Wars, from the Battle of Trafalgar on 21 October 1805 to 27 August 1816 when Lord Exmouth suppressed the Algiers slave trade. This decade begins after Nelson and Collingwood smashed the invasion threat at Trafalgar, subsequent Franco-Spanish sea power thus reduced to mere squadrons, desperately rebuilding at bases scattered around the globe. The British Cabinet and Admiralty could at last concentrate on capturing France’s overseas naval bases and colonial factories. During these tumultuous years the United Kingdom persistently made war on Napoleonic France and captured the fleets and colonies of those nations which were allied to Bonaparte, such as Spain, Denmark, Russia and Italy. In 1812 the Royal Navy overcame the intervention of the United States, a growing power that had won dramatic naval victories against the United Kingdom. While ministries changed, and with them the prospects for peace, Cabinets tended to adopt the traditional strategy: wield the Royal Navy to blockade the enemy’s ports, land the British Army wherever possible, and supply treasure and resources to what became, after Napoleon’s escape from Elba, a total of seven military coalitions.

Napoleon as First Consul, by Jean August Dominique Ingres c. 1803

Bonaparte crowned himself Emperor on December 2nd 1804. He was 35 years old. Painted by the studio of Francois Gerard.

War at Sea during the Georgian period

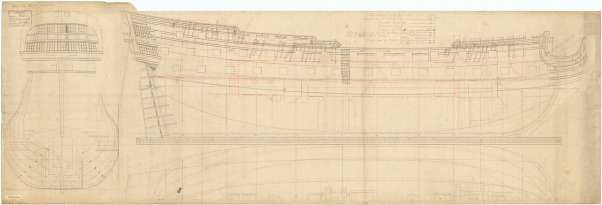

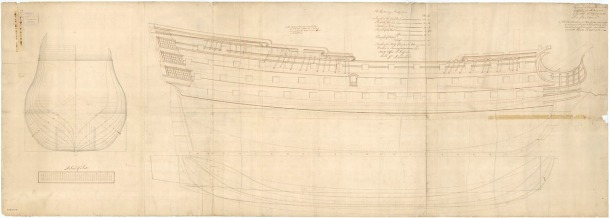

74-gun third rate ship of the line, 1790 pattern

The Royal Navy’s role as strategic implement was to carry out amphibious operations of a vast scale and complexity. The goal was often to influence the situation on the continent by creating military diversions (the Peninsula, Walcheren), capturing the enemy’s naval bases and destroying his fleets (Copenhagen, Mauritius, Basque Roads), or acquiring the enemy’s colonies. Convoying merchants and hunting privateers were vital trade protection responsibilities that regional commanders needed to master.

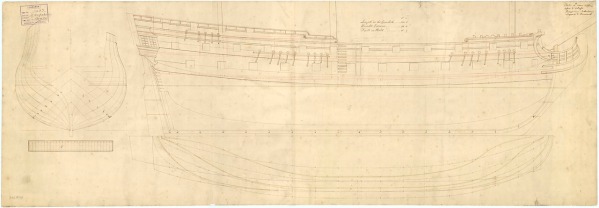

28-gun frigate c. 1763, 586 tons: 24 9-pdr cannons, four 3-pdrs on the quarterdeck

32 gun fifth rate, c. 1757, 660 tons

When these many global campaigns are considered to have occurred in addition to the nearly round the clock blockadade of European harbours, and by 1813 American ports, not to mention resources dedicated to convoy operations, logistical transportation and anti-privateering, it can be seen what influence an organization manned by not much more than 110,000 men in fact had in terms of executing Britain’s foreign policy and shaping world history.

Part I

The Wooden Walls

Emperor Napoleon I in his coronation robes, 1804, by Jean Louis Charles Pauquet

Late 18th century Western European commercial concentrations, from Fernand Braudel’s Wheels of Commerce. Paris and its environs represent the largest economic concentration

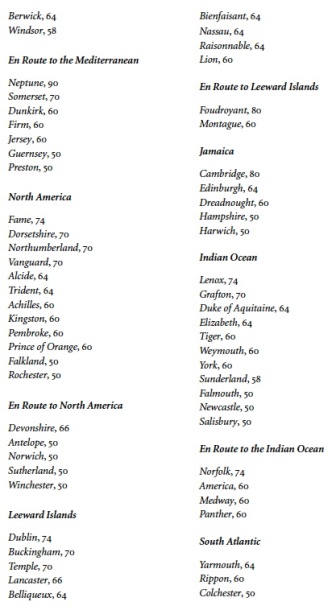

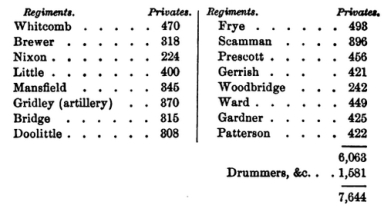

Establishment of the Royal Navy in 1806

The Royal Navy expanded exponentially after 1793 when Revolutionary France declared war upon the United Kingdom and Holland, the latter whom the British were obliged to defend by the treaty of 1788. Mobilization increased the navy’s manpower estimate from the peacetime establishment of 20,000 seamen in 1792 to 73,000 the following year, a figure that continued to increase until it reached 100,000 in 1796. This level was maintained until the peak of 114,000 was reached in 1812. Another 165,000 seamen manned the merchant marine in 1812 (up from 118,000 in 1792). Nor do these figure include the Royal Marines: 5,000 in 1793, 30,000 by 1810, when the art of amphibious warfare had been finely honed.[1] At the beginning of 1806 the Royal Navy possessed 128 ships of the line, 15 fifty-gun cruisers, with another 88 and 19 building, respectively, for a total establishment of 250 ships, discounting frigates, etc.[2]

Displacement tonnage of European fleets during 17th and 18th centuries

Numerical size of fleets during 18th century, ships of the line and frigates

The combined fleets of France and Spain were nearing parity with the Royal Navy when the Revolution broke out.

Chatham Dockyard, c. 1780s, by Joseph Farington

London Docks at Wapping, 1803, by William Daniell

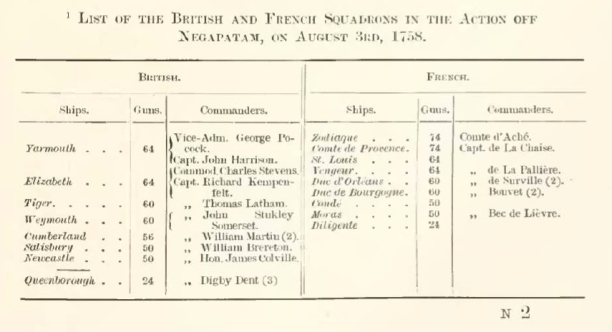

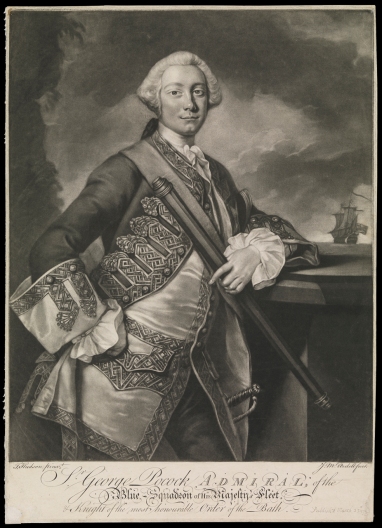

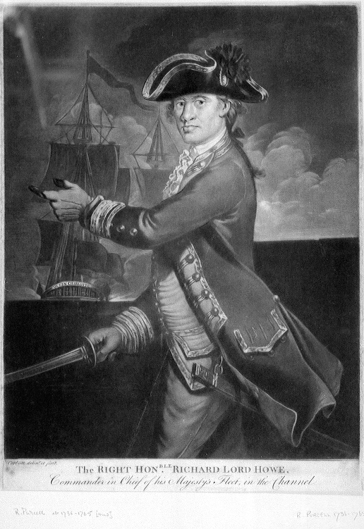

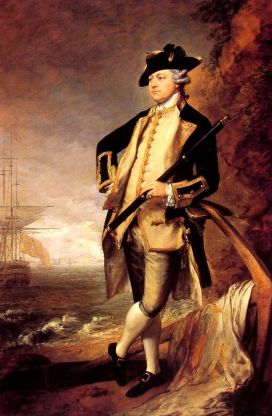

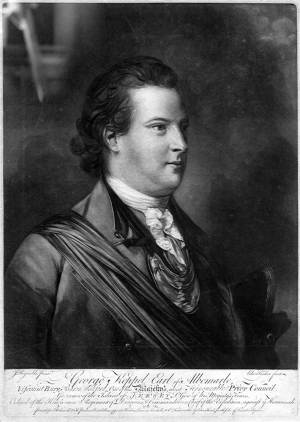

The generation of Royal Navy officers prominent in 1806 emerged from a long tradition of admirals, beginning in the hard school of the Elizabethan age. Prototypical practitioners such as the Earl of Lincoln, the Duke of Northumberland, Howard of Effingham, Sir John Hawkins, Francis Drake, Thomas Seymour, the Earl of Nottingham, the Earl of Essex, the Earl of Cumberland, Walter Raleigh, Richard Grenville, even Martin Frobisher, all illustrious predecessors who set the stage for their 17th century progeny. A new breed of sea generals evolved from the Civil War and Dutch Wars, including William Monson, George Somers, Edward Montagu, William Penn, the Duke of Northumberland, Robert Blake, George Monck, John Chichley, the Duke of York, the Duke of Grafton, and after 1688, Arthur Herbert, John Benbow, George Rooke, Stafford Fairborne, Viscount Torrington, John Leake and Edward Russell, whose 18th century successors were George Anson, George Clinton, Edward Vernon, Edward Hawke, John Byng, Edward Boscawen, John Byron, Samuel Barrington, George Pocock and James Cook, followed by George Rodney, Samuel Hood, John Harvey, Augustus Keppel, Richard Howe, George Darby, Robert Calder, and Charles Middleton.

Officer generations of the Royal Navy, from Elizabeth I to George III, 1558-1815

David Syrett, Nicholas Rodger, Roger Knight and Andrew Lambert are in agreement that the generation of officers who had risen to prominence since the beginning of the Napoleonic Wars were the successors of more than a centuries worth of professional experience.[4] The “service elite” who emerged out of the phase 1740-1792,[5] which included the War of Austrian Succession, the Seven Years War, the American Revolutionary War and the War of the First Coalition, had now produced the penultimate generation of 18th century officers: Alexander Hood, Adam Duncan, John Jervis, William Cornwallis, Hyde Parker, George Keith, John Duckworth, and Cuthbert Collingwood, whose uncompromising understudies and contemporaries, in particular those born between 1753 and 1775, included Horatio Nelson, James Gambier, Edward Pellew, Alan Hyde Gardner, James Saumarez, Thomas Thornbrough, Alexander Cochrane, Richard Strachan, Home Popham, John Warren, Robert Stopford, George Cockburn, Thomas Fremantle, William Sidney Smith, George Vancouver and Charles Stirling. It was these officers who carried Jervis and Nelson’s work through to completion.

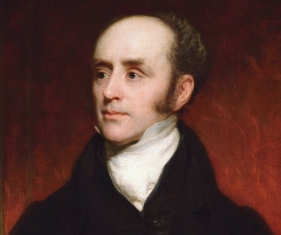

Charles Middleton, Lord Barham, First Naval Lord, 1805 – 1806, & Charles Grey, Viscount Howick, Barham’s Whig successor. Middleton, a talented frigate commander and dissembling administrator who cut his teeth reducing privateers in the Caribbean during the Seven Years War, spent forty years of a long career modernizing the navy and improving the quality and scale of dockyard works, a passion he shared with Lord Sandwich

The House of Lords and House of Commons in 1766

The House of Commons in 1793-94, by Karl Anton Hickel

The direction of higher strategy naturally co-mingled with the formulation of government policy. A succession of more or less successful Tory or Whig dominated coalition ministries transitioned in the period after 1805 from the strategic defensive to a global naval offensive, blockading France and intercepting French trade, then conquering Napoleons’ numerous island bases, containing the Americans, and intervening directly on the Continent.

British Cabinet office holders, 1803-1815, from Christopher Hall, British Strategy in the Napoleonic War, 1803-15 (1999)

Somerset House c. 1720. Location of the Navy Board, Victualling and Sick offices after 1789, engraving by Leonard Knyff & Johannes Kip, in 1795 by Joseph Farington & in 1809 by Rudolph Ackermann

Views of London in 1804, by William Daniell

The Great Fleet Battles

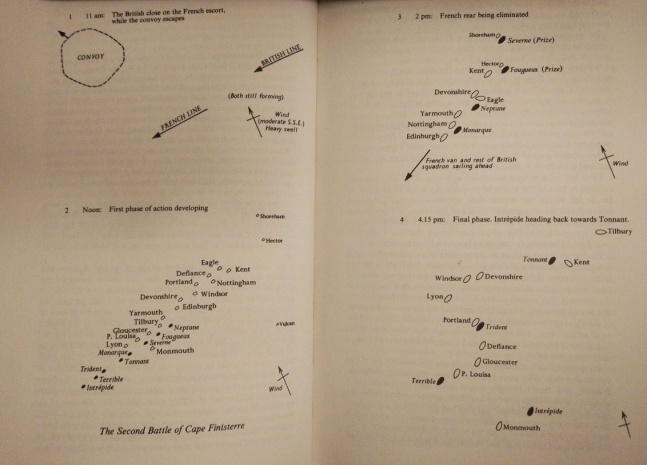

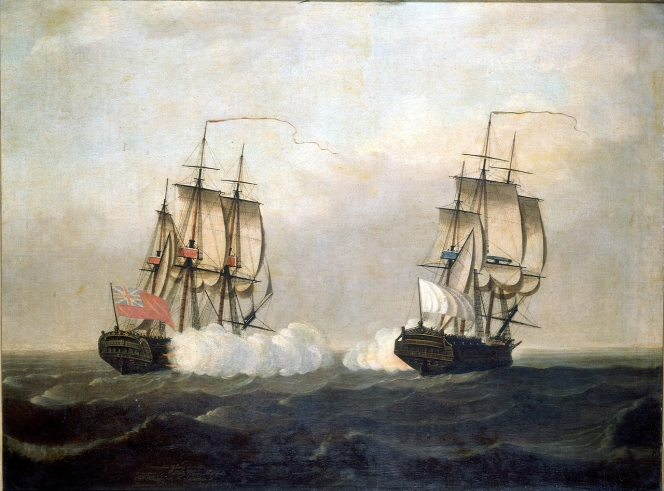

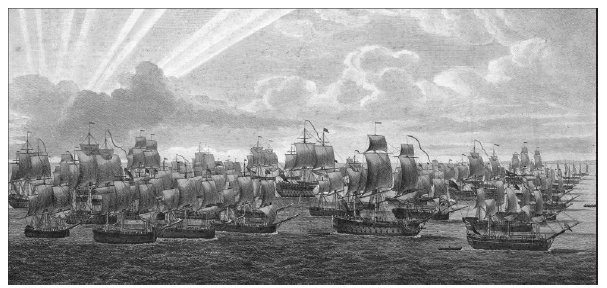

Despite being a force of not much more than a hundred thousand men, and with less than 150 ships of the line, the Royal Navy won a string of victories between 1794-1805 that pulverized French, Spanish and Dutch naval power: the Glorious First of June (1794), Cape St. Vincent (1797), Camperdown (1797), the Nile (1798), Copenhagen (1801), Cape Finisterre (1805) and finally Trafalgar (1805), concluded a spectacular series of fleet battles that shifted the maritime initiative to the United Kingdom.[3]

Lord Howe’s victory on the Glorious First of June, three hundred miles off Ushant, 1 June 1794, by Nicholas Pocock

John Jervis’ victory at Cape St. Vincent, 14 February 1797, by Robert Cleveley

Adam Duncan’s victory against the Dutch at Camperdown, 11 October 1797, by Thomas Whitcombe

Rear Admiral Horatio Nelson was in command of the blockade of Cadiz in 1797, by Thomas Buttersworth

Vice Admiral Nelson’s victory at Aboukir Bay, the Nile, 1 August 1798, by Nicholas Pocock

Viscount Nelson captures the Danish fleet at Copenhagen, 2 April 1801, by Nicholas Pocock

Admiral Sir Robert Calder engages the Franco-Spanish fleet off Cape Finisterre, 23 July 1805, by William Anderson

Lord Nelson’s decisive double line approach at Trafalgar, 21 October 1805

Nicholas Pocock’s 1808 painting showing Nelson and Collingwood’s divisions colliding with the Franco-Spanish battle line at Cape Trafalgar

HMS Victory at Trafalgar by Gerald Maurice Burn

Battle of Trafalgar by William Wyllie

The Battle of Trafalgar by Joseph Turner, c. 1822-24, & The Death of Nelson, by Benjamin West, 1806

1805 poster commemorating Nelson’s death and the victory at Trafalgar

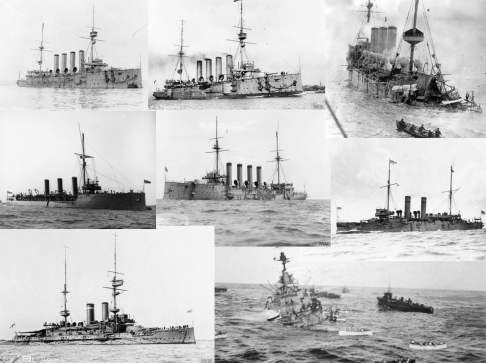

The antagonist of the Royal Navy in this violent struggle was the young Marine Nationale, at a low point after Trafalgar and Ortegal: in possession of only 19 solid ships of the line, but Spain could still marshal 57 and Holland would add another 16.[7] With its opponents so reduced the Royal Navy was therefore the largest navy in the world, indeed, outnumbering all of the European fleets combined (239 ships). As Charles Esdaile wrote, “Trafalgar’s significance is a matter of some dispute. In the short term it mattered little: Britain had already escaped the threat of invasion, and it did nothing to affect events in central Europe. Nor did it permanently establish the fact of British naval predominance, for the French shipyards were over the years able to make up Villeneuve’s losses and force the British to continue to commit immense resources to the naval struggle. All that can be said for certain is that, despite much bluster, Napoleon never again attempted to launch a frontal assault against Britain: henceforth victory would have to be attained by some form of economic warfare. In that sense, then, Trafalgar may be said to have changed the whole course of the war…” Napoleon could only commit to fight on the continent, hoping his privateers and detached squadrons would inflict some damage on Britain’s veritable cornucopia of trade.[8]

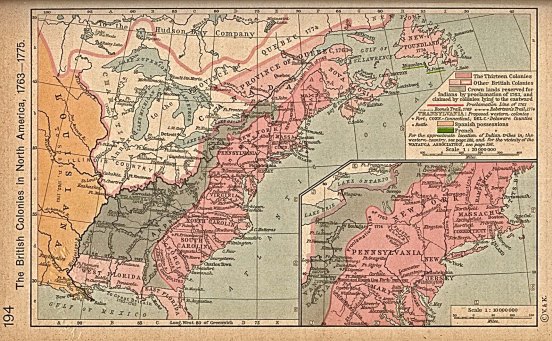

European alliances and battle locations, 1802-1815

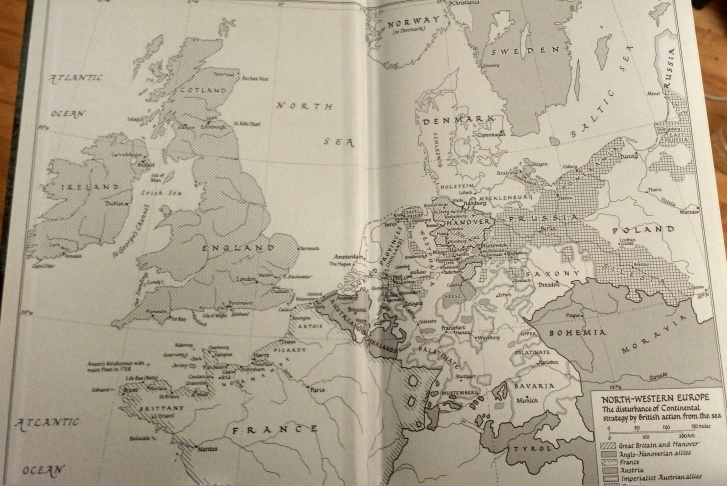

For the United Kingdom the challenge was now to take advantage of the destruction of the enemy fleets by leveraging British seapower to attack the French empire at its exposed flanks. As the editors of the Navy Records Society’s British Naval Documents, 1204-1960 described it, for Britain “the obvious alternative [to subsidizing continental coalitions] was to attack the empires of France and Spain, and disrupt their commerce; increasingly this strategy was used. The ‘blue water’ as opposed to ‘continental’ strategy aimed at defeating France by financial attrition.”[9] Napoleon was eager to do the same and after Trafalgar despatched squadrons to intercept British trade, such as the West Indian imports, which in 1803 were valued at £6.1 million and therefore had to be protected by the British from raiders crossing the Atlantic.[10]

Britain’s maritime strategy against revolutionary and Napoleonic France, from Paul Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery (1983), p. 125

For both Britain and France then, as James Davey put it, “… in late 1805, the focus of the naval war moved away from Europe into the wide expanse of the Atlantic Ocean.”[11] Britain’s essential expeditionary strategy came to the fore, and not only on the colonial front. Herbert Richmond and Roger Knight credit Secretary of War Henry Dundas with first advancing the colonial war policy, described by Knight as a “strategy of pre-emptive strikes against French ports”, exemplified first by the Ostend raid, carried out in May 1798 by Captain Sir Home Riggs Popham, a figure who will appear frequently in the various raids recounted below.[12] The expeditionary strategy that followed, as Julian Corbett recognized it, culminated in the Walcheren expedition of 1809: an attempt to leverage “the army to perfect our command of the sea against a fleet acting stubbornly on the defensive.”[13]

The Battle of Cape Ortegal

The Trafalgar campaign concluded when Captain Sir Richard Strachan’s squadron of five, tasked with blockading Ferrol, intercepted the squadron of Rear Admiral Pierre Dumanoir le Pelley, whose four of the line had escaped destruction at Trafalgar. On 4/5 November 1805 off Cape Ortegal, Strachan’s small force made quick work of the French squadron, taking all four of Dumanoir’s ships, but in turn missing Captain Zacharie Allemand, who slipped through to Rochefort having captured 43 merchants and three warships during his cruise.[6]

Views of the Battle of Cape Ortegal, 4/5 November 1805, Captain Sir Richard Strachan completes the destruction of Villeneuve’s fleet, by Thomas Whitcombe.

Part II

Napoleon’s Campaigns against Austria, Prussia and Russia: Ulm and Austerlitz, Jena, Eylau, Friedland & Royal Navy Operations: San Domingo, South Africa, South America, Copenhagen, The Baltic, The Peninsula

The spectacular defeat of the combined fleet at Trafalgar, although decisive in terms of Britain’s security from invasion, for Napoleon was merely in the background: the military action that season took place on Austrian and German soil, and it was here that the future of the Third Coalition was determined. The Austrian advance into Bavaria at Ulm under Mack was encircled by Ney, who had been despatched by Napoleon to hold what he thought was only a minor flank while the French Emperor executed his counter-march. Mack, however, had been totally surrounded between 15 – 17 October and then forced to surrender on the 20th, the day before Trafalgar.[14] The various French corps had inflicted 10,000 casualties and captured a staggering 50,000 prisoners, leaving the route to Vienna open.[15]

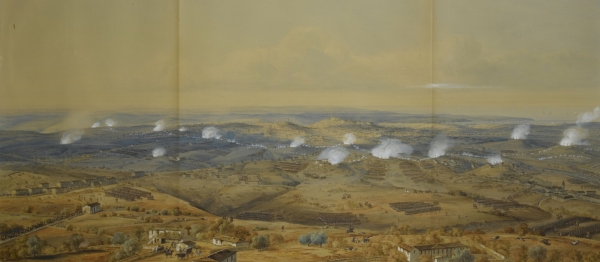

Napoleon encircles Mack’s Austrian corps at Ulm, 20 October 1805, by Giuseppe-Pietro Bagetti

The violation of Ansbach by the French on 3 October brought Frederick William III of Prussia around to a compromise with Alexander I Czar of Russia who, on 25 October, met with the Prussian king at Potsdam. By 3 November and the signing of the Treaty of Potsdam Frederick William was brought into the war alongside Russia.[16] After capturing the Austrian capital unopposed on 12/13 November, Napoleon turned against the Russians and Austrians as Kutusov and Buxhowden were combining between Brunn and Olmutz with 90,000 men on 19 November.[17] Napoleon arrived with Murat at Brunn the next day with 40,000 men – the Emperor’s forces were at this time precariously divided between the Hungarian, Viennese, and Italian fronts.[18] With both sides short on supplies, and winter lengthening, a decision had to be reached.

Napoleon issues his orders the morning of 2 December 1805, by Carle Vernet

Views of the Battle of Austerlitz, by Simeon Fort & Giuseppe-Pietro d’apres Bagetti, c. 1834-5

On 2 December, his army now massed at 65,000, Napoleon induced the Allies (commanded jointly by Czar Alexander and Emperor Francis) to attack at Austerlitz, routing both in hard fighting and inflicting 26,000 Allied casualties and taking 180 guns at the cost of only 7,000-8,000 French.[19] Francis II asked Napoleon for a truce on 4 December and on the 26th Austria agreed to the peace settlement known as the Treaty of Pressburg, ceding to Napoleon large portions of Italy and Germany.[20] This series of reversals for the Third Coalition seemed to do in William Pitt, who died on 23 January 1806.[21]

Napoleon meeting with Holy Roman Emperor Francis II on 4 December 1805, by Pierre-Paul Prud’hon

The War in 1806

French foreign minister Talleyrand, meanwhile, employed diplomacy to secure the treaty of Schonbrunn, 15 December 1805, neutralizing Prussia until August 1806.[22] After the New Year the Franco-Prussian alliance was solidified by the Treaty of Berlin, 24 February 1806, as a result of which Prussia annexed Hanover that March. Frederick William was in fact playing both sides and by July had resolved to join with the Russians.[23]

Napoleon at this time, between May and July, was focused on a brief campaign in Dalmatia during which Ragusa was occupied by the French, the Russians landed a force stationed on Corfu to take Cattaro, but Molitor arrived with reinforcements and forced the Russians to withdraw back to the Moldavian frontier.[24]

Terracotta bust of Charles James Fox, by Joseph Nollekens, c. 1791

Republican sympathizer Charles Fox, Foreign Minister in Grenville’s Talents ministry, was attempting to negotiate a way out of the war, as had been arranged previously with Revolutionary France by the Peace of Amiens in 1802. While Fox was willing to accept Napoleon’s suzerainty in Europe he was not willing to suffer French domination of the Mediterranean, where Napoleon was employing Joseph to secure Sicily. This effort was frustrated by Collingwood and Sir Sidney Smith (see below), and even Fox soon exhausted his patience with Napoleon’s machinations. At any rate Fox’s death on 13 September, and subsequent replacement by Lord Howick (Earl Grey), reduced the probability of successful peace negotiations to a small margin.[25]

In August 1806 Francis dissolved the Holy Roman Empire and became Francis I, Emperor of Austria

Napoleon’s next target was the Holy Roman Empire, towards the control of which Talleyrand concluded the treaty of Saint-Cloud on 19 July, prelude to the formation of the Confederation of the Rhine.[26] The Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor Francis II, seeing the writing on the wall and worried that Napoleon would soon usurp the title for himself, took the pre-emptive measure on 6 August 1806 of dissolving the Empire and proclaiming that he was now Francis I of Austria.[27]

Napoleon meanwhile consolidated his position by installing his relatives onto the thrones of the conquered territories: Joseph Bonaparte marched to Naples where, by the end of March 1806, he was declared King of the Two Sicilies; Louis Bonaparte was installed as King of Holland on 5 June, and Caroline Bonaparte (Murat’s wife) gained the Grand Duchy of Berg. Napoleon’s sisters, Elise and Pauline, received various parts of Venetia, Istria and Dalmatia.[28] In 1807 Jerome Bonaparte became King of Westphalia.[29]

Frederick William III, King of Prussia, by Wilhelm Herbig, c. 1818

The Prussians soon realized that they would face the same fate as the Austrians and Russians the year before if they did not take action immediately. Napoleon had 160,000 men in six corps, stretched between Baireuth and Coburg, with which he intended to march on Berlin.[30] The Emperor started his advance on October 8th and quickly routed the divisional strength Prussian forces before him. By evening on the 12th Davout’s 3rd Corps was at Naumburg, Lannes’ 5th Corps at Jena and Augereau’s 7th Corps at Kahla, effectively cutting off from Berlin the King’s 50,000 men.[31]

By the 14th Napoleon’s corps were combining at Jena where he now had 95,000 men, with Davout and Bernadotte in position to attack the Prussian left flank at Auerstadt.[32]

Battle of Jena-Auerstedt, 14 October 1806, by Carle Vernet and Jacques Swebach

Having cleared his lines of communication and smashed the Prussians at Jena, Napoleon continued the advance. Davout took Berlin on 25 October, enabling Napoleon to force the various German princes to surrender one by one, with Frederick William agreeing to Napoleon’s draconian terms on 6 November. This led on the 16th of November to the signing of the convention of Charlottenburg that formally took Prussia out of the war.[33] Napoleon imposed the Continental System as arranged by the Berlin Decree of 21 November.[34]

Slave trade abolished, 1807

The British cabinet took the extraordinary measure of abolishing the slave trade by the Slave Trade Act of March 1807, hoping thus to further weaken Franco-Spanish legitimacy by encouraging their colonial populations to revolt, as had Haiti in 1791, or join with the British. Napoleon responded with the Milan Decree of December 1807, collectively an attempt to isolate Britain through imperial tariffs – but enforcing this trade bloc necessitated strict repression of the European nationalities that were under Napoleon’s control.[35]

Napoleon enters Berlin, 27 October 1806, by Charles Meynier

The continental system was marginally successful in terms of increasing British deficits by restricting her access to the continental markets of Northern Europe. Exports to that region had been valued at £13.6 million in 1809, but fell to only £5.4 million in 1812, before recovering to £22.9 million in 1814. This decrease in European trade was relative, as total British exports and re-exports in 1800 were valued at £52.4 million, £60.9 million in 1810, £50.8 million in in 1812, and in 1814 at £70.3 million.[36] Thus it can be seen that the Continental System imposed some damage on Britain’s overseas trade in the years before Napoleon’s war with Russia and Britain’s war with America, but ultimately failed to cripple the economy of the United Kingdom.

1807, the Turn of Russia

Portrait of Alexander I, by Carl August Schwerdgeburth, c. 1813

The Russians meanwhile marshalled their forces in Poland, Bennigsen with 60,000 men by mid-November 1806 occupied Warsaw and Buxhowden’s 40,000 were moving to join him.[37] Napoleon marched to confront them on 25 November, the Russians withdrew, and Murat entered Warsaw on the 28th, where Napoleon joined him on 18 December.

Marshal Kamenskoi (Mikhail Kamensky)

Marshal Kamenskoi (Mikhail Kamensky) assumed command of the united Russian army. Napoleon advanced with his army of 120,000 foot and 25,000 horse, but the Russians withdrew, and on the 26th Lannes engaged Benningsen at Pultusk, while Davout and Augereau drove the Russians from Golymin, with Kamenskoi withdrawing to Novgorod.[38] Campaigning in the winter conditions was arduous and at the beginning of 1807 Napoleon returned to Warsaw while his corps laid siege to Danzig,

Count Levin August Bennigsen, by George Heitman and Thomas Wright

Bennigsen replaced Kamenskoi as Russian C-in-C, and on 15 January he marshalled his army at Biala. Bennigsen’s intention was to secure Konigsberg, where King Frederick William was then located, and then to march on Danzig and raise the siege. This was an error, as Napoleon quickly realized he could once again cross the Allies’ lines of communication and execute a repeat of his Jena maneuver.

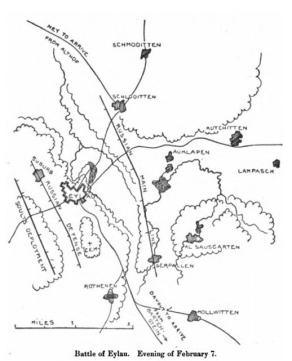

Russian and French deployments before Eylau, from T. A. Dodge, Napoleon, vol. II (1909)

Napoleon’s intention, before taking command of the vanguard, was to have Soult, Ney, Davout, Murat, Augereau, and Bessieres variously surround the Russians before destroying them with a frontal attack.[39] Napoleon marched from Warsaw on 30 January with 75,000, while despatching orders for Ney and Bernadotte to join him with another 34,000.[40] Bennigsen luckily intercepted some of Napoleon’s orders intended for Bernadotte and realized his danger,[41] immediately ordering a concentration at Allenstein, he discovered to his surprise Soult and Murat already there. Benningsen marched north, trying to cross the Alle, but was blocked by the shadowing French. With the French corps closing in Bennigsen now began a series of retreats while Napoleon hastened to turn the Russian flank and attack their rear.

Battle of Eylau, Bennigsen check’s Napoleon’s advance, 7 February 1807, by Giuseppe-Pietro Bagetti

The French closed in on February 6th, fighting some small engagements, and at last forced Bennigsen, with 126 battalions and 195 squadrons (75,000-80,000 men) to fight on the 7th at Eylau, where Soult was waiting, having stormed that place with the bayonet while the rest of the French army closed in. Although the Russians outnumbered the French, and possessed far more artillery, Napoleon’s corps were more mobile and their commanders fully understood their roles in the operational plan: while Murat, Augereau, and Soult held the centre at Eylau with 36,000 men, Davout would then march up on the right flank with 18,000, while Ney took the left flank with 15,000.[42] Bennigsen began shelling Eylau on the 8th, but was unaware of his danger as the French flanks arrived, with Davout intending to cut-off the Russian retreat.[43]

Heavy snow fall now obscured the battlefield, and by dawn on the 9th Napoleon had fought Bennigsen only to a draw, the arrival of the Prussians under L’Estocq amidst the poor weather deflecting Davout’s flank attack.[44] What had at first seemed like a another Jena devolved into a terrible attrition battle, Napoleon’s first serious check: there were 40,000 casualties left in the snow, the Grand Armee having suffered between 20,000 and 25,000 killed and wounded to the Russians’ 11,000, with another 2,500 prisoners destined for French prisons – still, Napoleon held the field after the slaughter and so the Russians withdrew to Konigsberg.[45]

Napoleon after Eylau, 9 February 1807, by Jean-Baptiste Mauzaisse

The carnage at Eylau had been a serious wakeup call for Napoleon, who promptly despatched General Bertrand to meet with Frederick William and try to arrange a peace settlement.[46] Napoleon’s corps required all spring to regain their strength, but then Danzig, which had been under siege since 11 March, surrendered on the 27th of May, and at last this enabled Napoleon time to mass against Bennigsen’s base at Konigsberg.[47]

Louis-Nicolas Davout, perhaps Napoleon’s ablest commander, as a Lieutenant Colonel in 1792 by Alexis-Nicolas Perignon, c. 1834, and Marshal Davout by Pierre Gautherot

Bennigsen took the offensive at once, departing Konigsberg on 5 June with his 50,000 men, but was badly outnumbered by Napoleon, who began once again to concentrate his corps against Bennigsen’s lines. Bennigsen brushed aside Ney’s corps, but soon found himself facing Napoleon’s combined army and so withdrew to his entrenchments at Heilsberg.[48] Here Napoleon’s plan of attack for 10 June was to have Murat, Soult and Lannes pin the Russians, while Ney, Davout and Mortier cut off Bennigsen’s retreat.[49]

Napoleon visited Murat and Soult’s headquarters that afternoon, and in the evening began to develop a frontal attack despite this being strictly contrary to the orders he had given his marshals. The result was a strong repulse of both Murat and Soult.[50] Despite this setback the turning movement continued to develop onto the 11th; Bennigsen realized that Davout was about to turn his flank and he withdrew from Heilsberg that night, reaching Friedland on the 13th.[51]

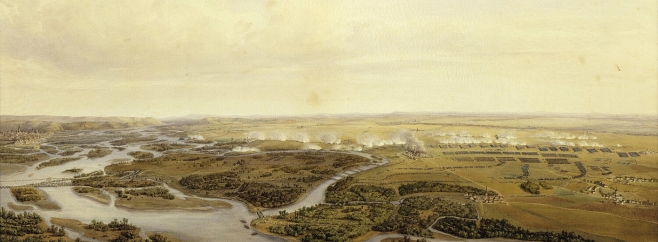

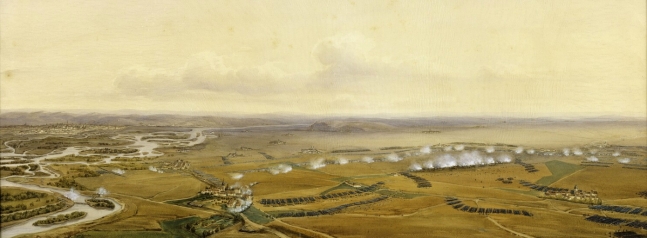

Battle of Friedland, showing Bennigsen being squeezed back against the Alle river

Napoleon commanding at Friedland, 14 June 1807, by Carle Vernet

There on the morning of the 14th Lannes’ corps encountered the Russians first, but Napoleon arrived at noon (having camped the night before at Eylau, site of the bloody winter battle only five months earlier), to support the 35,000 already engaged with another 50,000, pressing his attack before Bennigsen could bring his combined Russo-Prussian force of 90,000 into action.[52] Napoleon stove in Bagration’s corps after which the Russians collapsed, scrambling to get back across the river.[53]

Battle of Friedland, 14 June 1807, by Simeon Fort

The result was 15,000 Russian casualties to 7,500 French, and Bennigsen’s withdrawal to the Niemen, whither Alexander I asked Napoleon for a truce. The following negotiations culminated on 7 July 1807 with the Treaty of Tilsit.[54] This agreement between French Emperor and Russian Czar took the Russians out of the war, dismantled the Fourth Coalition, and left the British isolated. As Kissinger later phrased it: Napoleon arrived at Tilsit “to complete the division of the world.”[55]

After defeating Count von Bennigsen on 14 June, Napoleon and Czar Alexander I met in the middle of the Neman River to sign the Treaty of Tilsit, 7 July 1807

Alexander I and Napoleon meeting on the Neman River, by Francois-Louis Couche

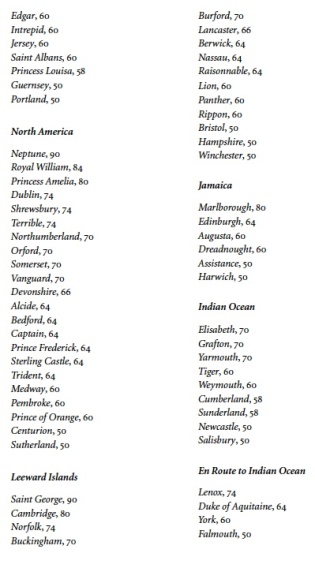

As 1808 dawned the Napoleonic Empire was at its height. Despite Napoleon’s control over the European continent, he did not possess the naval power to confront Britain. The Royal Navy thus continued its long-term naval blockade and began to recapture the various Franco-Spanish overseas colonies.

Europe in July 1807, after the Treaty of Tilsit

The War at Sea Renewed, 1805 – 1808

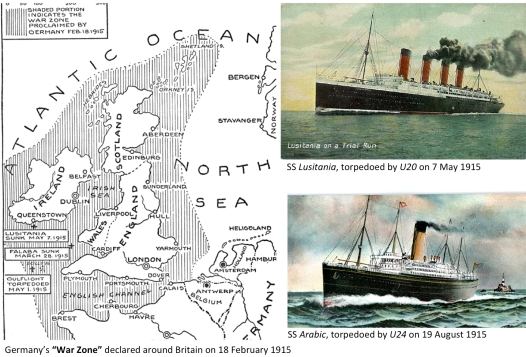

On 13/14 December 1805, when Admiral Cornwallis’ blockading force withdrew to Torbay for the winter, two French squadrons escaped Brest. The first, under Rear Admiral Jean-Baptiste Willaumez, made for the Cape of Good Hope and the South Atlantic, while the second, under Vice Admiral Corentine de Leissegues, sailed for the West Indies with orders to land 1,000 men at San Domingo and then intercept merchant traffic off Jamaica.[56] At the Admiralty this development was recognized as the transition point: Napoleon’s naval strategy had ceased to revolve around invasion through main action and instead became a prolonged guerre de course.

Prevailing winds in the North Atlantic

Rear Admiral of the Blue William Cornwallis, c. February 1802

The Brest squadrons, commanded by Vice Admiral Corentin Leissegues and Rear Admiral Jean Baptiste Willaumez, escaped Cornwallis’ Channel blockade on 13 December 1805

Vice Admiral Sir John Warren, c. August 1800

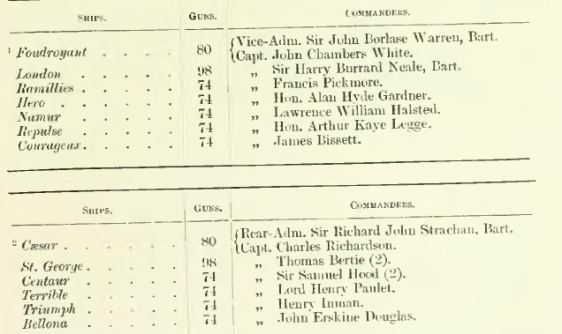

Vice Admiral Warren and Rear Admiral Strachan’s squadrons

Vice Admiral Sir John Warren, newly promoted on 5 November 1805, and Sir Richard Strachan, likewise promoted to Rear Admiral, were despatched on December 24th with orders to intercept the Brest squadrons and ensure they were not allowed to take prizes amongst Britain’s lucrative West Indian and South American trade.[57] Warren, in his flagship Foudroyant (80, Captain John C. White), with six of the line, sailed south after Willaumez early in January 1806, but could not locate his quarry.

38-gun fifth rate (1794), HMS Diana

Having been joined by Captain Sir Harry Neale in HMS London (98), Warren shifted his flag and on the 13th of March, while they were cruising off the Cape Verde Islands, Foudroyant and the 38-gun frigate Amazon of Captain William Parker, took the 74 or 80-gun Marengo, Rear Admiral Linois’ flagship, along with the frigate Belle Poule (40). Linois had been in the process of returning from the East Indies, where he had been displaced by Rear Admiral Edward Pellew’s efforts.[58]

Vice Admiral Warren’s London (98, Captain Sir Harry Neale), with Amazon (38, Captain William Parker) and Foudroyant (80, Captain John Chambers White) takes Linois’ Marengo and Belle Poule (40) on 13 March 1806

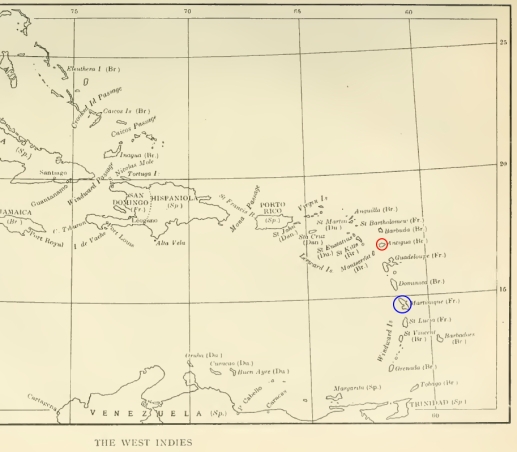

After returning to Spithead with his prizes Warren was ordered to resume the search for Willaumez’ squadron. Again Warren was unable to locate it in North American waters during 1806. In October 1807 Warren was promoted to C-in-C North America.[59] Strachan, for his part, had no more luck, having arrived at Barbados early in August 1806, but had in fact passed not more than 60 miles from Willaumez on the night of the 18th.[60]

Engraving of Sir Samuel Hood, c. November 1806, after losing his right arm in the September action.

On 25 September 1806 Commodore Samuel Hood, flying his flag in the Centaur (74) and with Monarch, Mars, and three other warships, captured a squadron of five French warships, including four French 40-gun frigates, which had been heading from Rochefort to the West Indies.[61] Hood lost his right arm to a musket ball during the action. Lauded as a naval hero, Hood accompanied Lord Gambier in the Copenhagen expedition in 1807.[62] A similar success story was that of Captain Cochrane in the Imperieuse (40) who, between 13 December 1806 and 7 January 1807, captured or destroyed 15 French ships.[63]

Hood’s action against the Rochefort Squadron, 25 September 1806, engraving by John Heaviside Clark

HMS Leopard detains USS Chesapeake, 21 June 1807, by Irwin John Bevan

Here we must briefly mention the Leopard-Chesapeake incident, a significant development in the prelude to the intervention of the United States in 1812: On 21 June 1807 the 50-gun HMS Leopard, captained by Salusbury Humphreys, intercepted the 38-gun USS Chesapeake with orders to recover deserters known to be aboard.[64] Chesapeake refused to allow a search and so Leopard fired broadsides at the American warship until it surrendered. Four sailors were taken off the frigate, but only one proved to be a Briton; this despite there being 2,500 British seamen serving in the American merchant marine: a major diplomatic embarrassment for the British government that dramatically weakened relations between the two nations.[65]

The West Indies and the Battle of San Domingo, 6 February 1806

Admiral Sir John Duckworth, c. 1809-1810 by William Beechey

The other side of the Brest squadron’s story revolved around the command of Admiral Sir John Duckworth who, after Trafalgar, had been ordered by Collingwood to blockade Cadiz. On Christmas Day 1805 Duckworth encountered Leissengues’ squadron and chased him to the West Indies.[66] Duckworth detached Powerful (74) on January 2nd to join Rear Admiral Pellew in the East Indies, and then steered for Barbados where he arrived on the 12th.

Duckworth’s Cadiz blockade squadron in the chase against Leissengues’ six of the line.

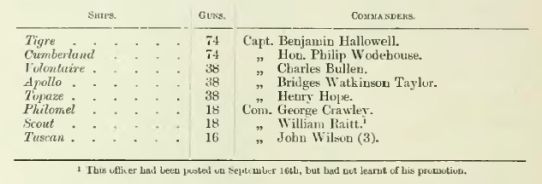

The next week Duckworth was joined by Rear Admiral Alexander Cochrane in the Northumberland (74) and Captain Pym in the Atlas (74). Duckworth at first had no intelligence regarding Leissengues’ deployments and thus intended to re-cross the Atlantic and return to his blockade station, but on February 1st the carronade sloop Kingfisher informed him of French warships near San Domingo. Acting on this intelligence Duckworth made sail for San Domingo and on February 5th arrived at the eastern end of the island. There he was joined by the 36-gun frigate Magicienne, bearing intelligence that further confirmed the reports of nearby French warships. On the morning of the 6th Duckworth sailed for the harbour of San Domingo where his frigates identified Leissengues’ squadron, in fact anchored and deploying troops ashore since 20 January.[67]

John Pitt’s sketchbook of British warships and merchants at Barbados (including the 98-gun Temeraire)

Leissengues immediately realized the danger and at 7:30 am slipped anchors. Duckworth, who had six of the line, mainly cruisers, and two frigates plus his carronade sloops, was outnumbered by Leissengues’ nine warships, including three frigates.

Chart of Battle of San Domingo from J. Davey, In Nelson’s Wake

The Battle of San Domingo, 6 February 1806, by Nicholas Pocock

In the action that followed Duckworth split his squadron into two columns, with a third frigate group cutting off the French escape route, and engaged the French line in two attacks. At the front of the line Duckworth’s flagship Superb engaged the Alexandre at 10:10 am, while the Northumberland (74) engaged the Imperial, the latter mounting 120 or 130 guns, and ultimately held off three RN warships for nearly two hours. Duckworth’s division was sustaining heavy casualties but as planned Rear Admiral Thomas Louis came up leading his division in the Canopus (80) and poured in fire against the French line.[68] This movement swung the battle in Duckworth’s favour, and at 11:30 am Leissengues in Imperial attempted to steer away, only to run aground ten minutes later.

80-gun second rate HMS Canopus, French capture from the Nile

Loss of the Indiaman Bangalore (1802), by Thoomas Tegg

In the event Duckworth captured one 80, two 74s, and forced the Imperial and the Diomede (72) to wreck themselves ashore, and they were subsequently burned. The French frigates and a corvette escaped. The British suffered 64 (or 74) killed and 264 or 294 wounded, the French suffered between 500-760 killed and wounded.[69] Duckworth for his part had justified his movements, although he likely would have faced recrimination had he returned home empty-handed, having abandoned his station in the pursuit.[70] Vice Admiral de Leissegues, for his part, in fact escaped the destruction of his squadron and later returned to Europe.

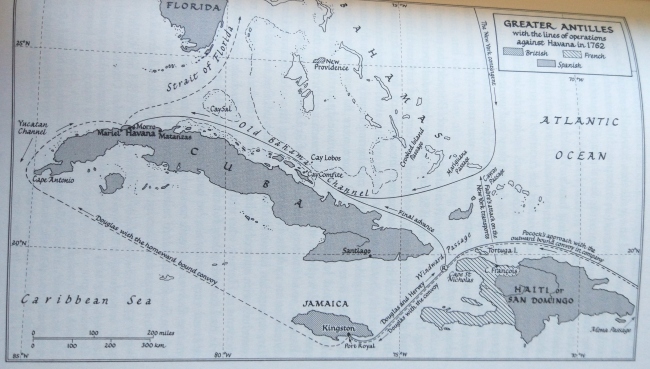

Caribbean theatre of operations

Rear Admiral Willaumez continued to evade the RN and sailed for the Cape of Good Hope. There he learned of Commodore Home Popham’s success (see below), preventing him from taking any action and so sailed for South America but eventually concentrating at Martinique on June 24th, before departing on 1 July for Montserrat.[71] Willaumez was then spotted on the 6th off Tortola by Rear Admiral Cochrane, whom Duckworth had detached after San Domingo to observe Martinique, but as he was then preparing to escort a merchant convoy, and as Cochrane’s four of the line were outnumbered by Willaumez’s six, with a convoy of 280 merchants to protect, pursuit was impossible.[72]

Willaumez, who had Jerome Bonaparte with him, did not wait around to confront Cochrane and instead made for Jamaica to intercept merchant traffic there, in the process seizing a number of prizes. Jerome in the Veteran (74), for whatever reason, made an ill-advised sortie out of the Caribbean and eventually returned to France. Willaumez was compelled to search north for Napoleon’s youngest brother, failed to locate him, and towards the end of August returned to the Caribbean where he docked at Havana.[73] Willaumez ultimately dispersed his squadron, and his ships variously met their fates along the American seaboard, although the Foudroyant made it back to Brest in February 1807.[74]

Vice Admiral James Dacres, C-in-C Jamaica, by Robert Bowyer, R. Page and Joyce Gold, 31 October 1811

Operations in the Caribbean continued late in 1806: St. Thomas was taken from the Danish on 21 December by Rear Admiral Alexander Cochrane and General Bowyer, and St. Croix was quietly occupied on Christmas Day.[75] This series of successes was immediately followed up by the capture of the Dutch island of Curacao. On 29 November 1806 Vice Admiral James Dacres at Jamaica despatched Captain Charles Brisbane in the Arethusa (38) with Latona (38, Captain James Wood), and Anson (44, Captain Charles Lydiard), with orders to join with the Fishguard (38) when they located it, then reconnoitre the island of Curacao to determine if the Dutch there were willing to join the Allies.[76] Brisbane’s squadron reached Aruba on 22 December, collecting the Fishguard next day. Brisbane relied on surprise and intended to force the Dutch to concede at cannon-point. Besides Fort Republiek and Fort Amsterdam, the latter with 60 cannon, there was a Dutch 36-gun frigate, a 22-gun corvette, and two armed schooners in the harbour.[77]

Captain Sir Charles Brisbane, knighted for the capture of Curacao, engraving by William Greatbach from drawing by James Northcote, c. 1837

The capture of Curacao, 1 January 1807 by Thomas Whitcomb

Arethusa was flying a flag of truce when Brisbane led the squadron into the harbour at 5 am on 1 January 1807. The Dutch wisely ignored the flag and opened fire. The Fishguard at the rear of the line ran ground, and at 6:15 am Brisbane opened fire and moved in alongside the Dutch frigate before Brisbane himself led the boarding action that captured it. Latona and Anson took the Dutch corvette. Brisbane followed up this coup by leading the shore party that stormed Fort Amsterdam at 7:30 am. Afterwards the seaman and officers returned to their ships and engaged Fort Republiek, silencing it by 10 am. At noon the island’s governor, M. Pierre Jean Changuion, surrendered. The British had lost three killed and 14 wounded, while the Dutch suffered nearly 200 casualties, a testament to the value of surprise and swift execution.[78]

The East Indies

Disposition of British squadrons in January 1807, from Christopher Hall, British Strategy in the Napoleonic War, 1803-15 (1999)

Rear Admiral Edward Pellew was appointed C-in-C East Indies in April 1804, and thither he departed that July in the Culloden. For political reasons related to Pellew’s defence of Addington’s ministry, Henry Dundas, Lord Melville, who superseded St. Vincent at the Admiralty, decided to split Pellew’s command in half, with Rear Admiral Thomas Troubridge taking the eastern half. Troubridge departed England on 27 April 1805 in the Blenheim (74). This was a situation guaranteed to produce confusion and the results were far from optimal.[79]

French East Indiaman of 1764, 900 tons, 20-25 guns

Troubridge was escorting a convoy of 11 merchants when, on 6 August 1805, after departing Madagascar, he fell in with Admiral Linois in the Marengo, who however declined to engage, but as we have seen was captured in March the following year by Vice Admiral Warren. Troubridge rendezvoused with Pellew’s squadron at Madras on 22 August and Pellew, ignoring Troubridge’s orders to take half of the East Indies squadron under his command, simply added Troubridge to his existing squadron – to the latter’s outrage.[80]

The BEIC trade from the factory at Canton was exposed to French interception, as Admiral Linois had attempted in the Malacca Strait on 14/15 February 1804. Linois with Marengo (74), Belle Poule (40), and Semillante, plus the corvettes Berceau and Aventurier engaged Captain Nathanial Dance’s convoy of 39 ships, who, with great pluck, turned the tables on Linois and chased him off. Paintings by William Daniell & Thomas Sutherland, September 1804

Large Indiaman, Scaleby Castle (1798), 1,237 tons, 26 18-pdrs

Pellew intended to have Troubridge convoy the China trade, a vital mission given Linois’ presence off Sumatra and the lack of any escort for the BEIC ships in those waters. Indeed, Linois brought five captured BEIC ships into Mauritius between 1804-6, but eventually exhausted his supplies and was thus intercepted and captured on 13 March 1806 by Warren off the Canaries while returning to France.[81] Troubridge, for his part, felt that he was being shuttled off to an unimportant command by Pellew and was so upset that he preferred to stay behind at Penang in the sloop Rattlesnake, presumably sour grapes. The disconnect between Pellew and Troubridge was equalized somewhat on 9 November when Troubridge was promoted to Rear Admiral of the White, the same rank as Pellew, but the situation in London shifted rapidly following the death of Pitt and the return to power of the Whigs under the Talents ministry indicated a change in policy.

Edward Pellew as Captain in 1797, painted by Thomas Lawrence, also engraving by Thomas Lawrence

Rear Admiral Sir Thomas Troubridge, engraving based on drawing by Sir William Beechey

As such Pellew ultimately came out on top and in April 1806 orders were despatched to make Troubridge C-in-C Cape of Good Hope, following on Commodore Popham’s operation (see below). These orders did not arrive until January 1807 and Troubridge then departed from Madras on 12 January in the aged Blenheim (90) with the Java (36), a Dutch prize, and the brig Harrier (18). Tragically Troubridge’s squadron was caught in a storm early in February off Madagascar, with the Blenheim and Java foundering with all hands.[82] Harrier returned to Madras and informed Pellew, who sent Troubridge’s son in the Greyhound to search, the French at Mauritius even offering assistance, but nothing was ever heard from Troubridge’s lost squadron.

Illustration by N. C. Wyeth for the 1911 edition of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island

Pellew for his part had his eye on the island of Java, and in June 1807 despatched from Madras Captain Peter Rainier in the Caroline (36) with Commander Fleetwood Pellew, Sir Edward’s son, in the Psyche (36), to observe the the harbour of Griessee where he suspected two Dutch 68-gun ships were located.[83]

Nicholas Pocock’s drawing of Captain Fleetwood Pellew of the Psyche engaging two Dutch frigates at Samarang roadstead, Java, 31 August 1807

Captain Pellew in fact discovered from a prize secured on 30 August that these Dutch warships were present at the harbour of Samarang, but were not in sailing condition. The next morning Pellew despatched Lt. Lambert Kersteman and acting Lt. Charles Sullivan in Psyche’s boats to enter the roadstead. There they found a number of merchants, including the armed merchantmen Resolutie and Ceres, plus the corvette Scipio (24). Psyche’s boatcrew captured an armed schooner and a merchant brig, both of which they burned, while Psyche chased the other merchants and Scipio to ground, the Dutch frigates then surrendering one by one and were taken as prizes.[84]

Rear Admiral Pellew’s squadron for the capture of the Dutch ships at Griessee (Surabaya), Java, 5/6 December 1807

Suitably reinforced, Rear Admiral Pellew sailed to Java and on 5 December and demanded the surrender of the warships at Griessee (Surabaya), an ultimatum that was refused. The next day Pellew sailed in with the Culloden (74) and Powerful (74), defeating a small 12-gun fort. The Rear Admiral compelled the local authorities to acquiesce to his terms, although the senior Dutch officer, Captain Cowell, had already scuttled his ships including the Revolutie (68), Pluto (68), the hulk Kortenaar (68), and two transports.[85] Thus, by the beginning of 1808, the Dutch naval presence in the East Indies had been terminated, if not all its various colonies yet captured.

The South African Expedition

Prevailing winds in the South Atlantic

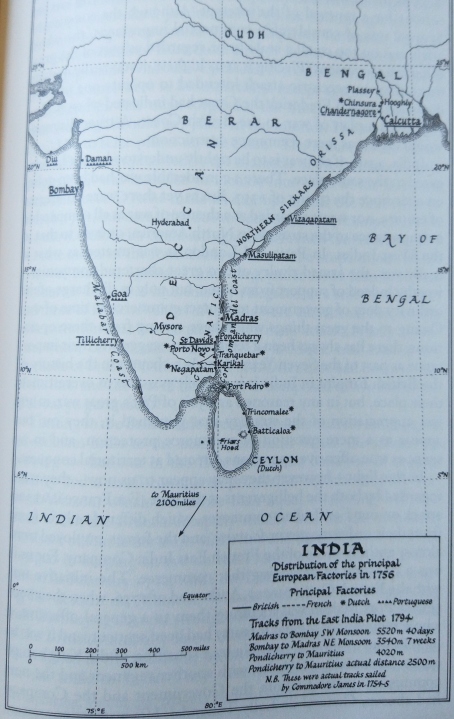

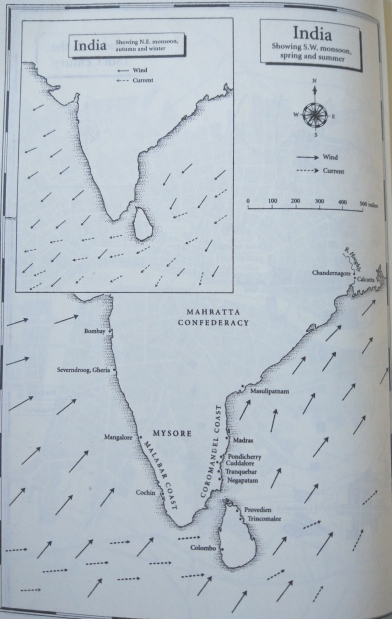

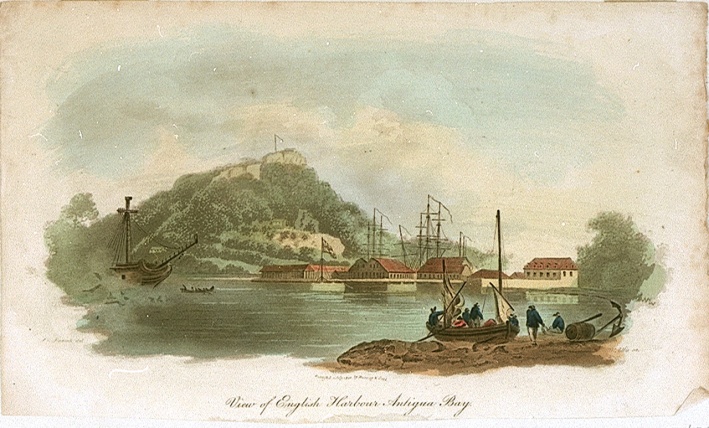

South Africa and Mauritius, control points on merchant routes from India and China

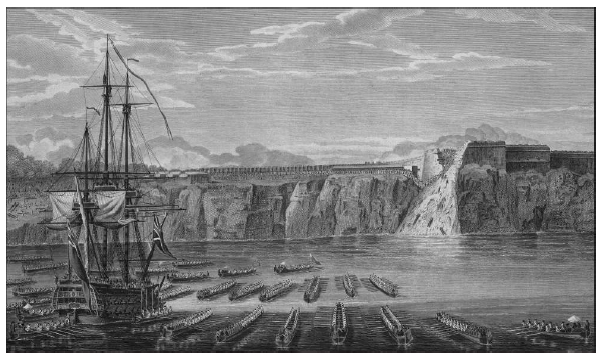

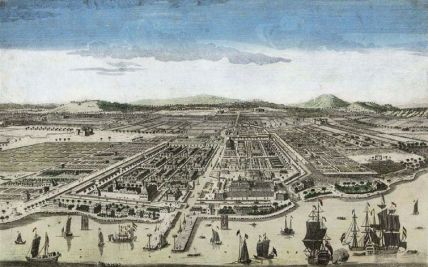

Cape Town belonged to the Dutch but had been taken in 1801 and then returned in the peace of 1803. With the Netherlands now under Napoleonic occupation the capture of Cape Town once again became a priority. Between August – September 1805 an expedition was outfitted to retake Cape Town, commanded by Commodore Sir Home Riggs Popham and carrying 5,000 troops under Major General Sir David Baird.[86] Popham, flying his flag from the 64-gun Diadem, sailed south from San Salvador on 26 November and on 4 January 1806 anchored at Robben Island, Table Bay, before proceeding to land Baird’s men over the course of the 6th and 7th. The Leda (38), Encounter (14) and Protector (12) carried out a bombardment and landed men to clear the enemy from the area of Blauwberg Bay (Bloubergstrand) while the main landing was underway.[87]

Home Riggs Popham as a 21 year old Lieutenant in 1783

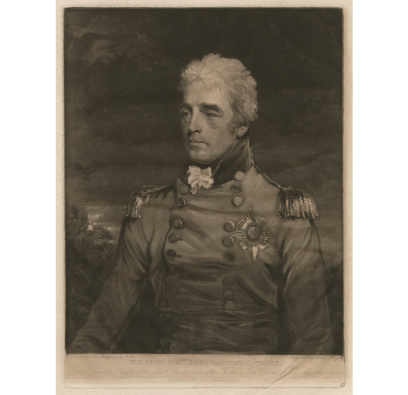

Lieutenant General Sir David Baird, c. 1814 by Thomas Hodgetts

On January 8th the expeditionary force marched towards Cape Town and defeated a Dutch defensive force under Lt. General J. W. Janssens, inflicting 700 casualties and sustaining 15 KIA and 189 WIA. The capital was quickly secured when the Dutch capitulated on the 10th, with Popham and Baird capturing 113 brass and 343 iron cannon. Added to the spoils was the 40-gun French frigate Volontaire, captured on 4 March when it approached the British squadron thinking them Dutch – although the Dutch had burnt their own 68-gun ship Bato on 13 January to prevent capture.[88] With this singular triumph under his belt, the amphibious enthusiast Popham next prepared an expedition to cross the Atlantic and take Buenos Aires: the ambitious objective was to capture all of Spanish South America.

Commodore Popham’s squadron for the Cape of Good Hope operation

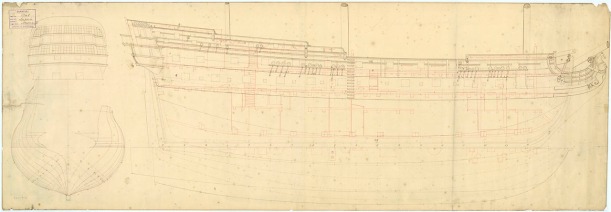

1,375-ton 64-gun (1774) third rate

940-ton 38-gun (1780) frigate

The Capture of Buenos Aires: The South American Expedition of 1806

South America in 1806, organized into conglomerated Spanish and Portuguese Viceroyalties.

South America in 1806, organized into conglomerated Spanish and Portuguese Viceroyalties.

Commodore Sir Home Riggs Popham, c. 1807 by Anthony Cardon, copied from Mather Brown;

Major General Williams Carr Beresford

Popham sailed from South Africa on 14 April 1806 with one of Baird’s regiments, 1,200 men from the 71st Regiment under Major General William Beresford, plus an attached Royal Marine battalion of 435.[89] With his flag in the Narcissus Popham made haste for Flores to gather intelligence, arriving there on 8 June, followed by the rest of the squadron and its transports five days later. While the Diadem blockaded Montevideo and Raisonnable and Diomede held the mouth of the Rio de la Plata, Popham with the transports worked their way up the river, arriving off Point Quilmes, 12 miles from Buenos Aires, on 25 June. The task force was put ashore that night and in the morning General Beresford brushed aside the Spanish garrison of 2,000. A capitulation agreement was negotiated on 28 June and signed on 2 July by the governor Don Josef de La Quintana, Viceroy of the Rio de la Plata: Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay and Bolivia had been seized.[90]

The relief squadron under Rear Admiral Charles Stirling

Popham and Beresford’s triumph was short lived however as 2,000 Argentinians under the command of French general Santiago Liniers retook Buenos Aires between 10-12 August (the British suffering 48 KIA and 107 WIA) and then imprisoned the rest of the garrison, including Major General Beresford.[91] A relief expedition under Rear Admiral Charles Stirling, with Brigadier General Sir Samuel Auchmuty, arrived on 3 December and Popham was sent back to England in disgrace. On 3 February Stirling and Auchmuty captured Montevideo with the loss of 192 killed, 421 wounded and eight missing. Upon returning to England on 20 February Popham was immediately arrested and tried for court martial, although in the event receiving only a sever reprimand and his rank being reduce from Commodore to Captain.[92] A fateful decision as we shall see.

Lieutenant General John Whitelocke, engraving by James Hopwood, based on drawing by Edward Hastings, March 1808

In May Auchmuty was superseded by Brigadier General Crauford who brought 5,000 reinforcements, a figure further reinforced by the arrival of Lt. General John Whitelocke and Rear Admiral George Murray in the Polyphemus (64) on 15 June. The army went ashore at Buenos Aires on 28 June and launched an attack against the city on 5 July. Although they carried the city the cost of 2,500 casualties was excessive. Whitelocke agreed thereafter to evacuate the entire operation and the adventure was terminated as the Talent’s ministry collapsed. Whitelocke was later dismissed from service.[93]

Collingwood in the Mediterranean

Baron Collingwood in 1807, copy by Henry Howard from painting by Giuseppe Politi

In the spring of 1806 Napoleon moved to consolidate his position in Italy, in particular by reducing Ferdinand of Naples. Sicily provided supplies to Britain’s Mediterranean naval base at Malta, much as Reunion supplied Isle de France at Mauritius, and both islands were needed to assemble and victual expeditions, as was done in Egypt and at the Dardanelles.[94]

Rear Admiral Sir William Sidney Smith, by Edward Ball, March 1803

Unable to prevent the loss of Naples, but before the end of March when Napoleon’s forces overran that theatre, the Allies’ mixed Anglo-Russian force of 10,000 was withdrawn to Sicily and Ferdinand himself was evacuated by HMS Excellent.[95] Collingwood, hoping to create some problems for the French, detached Rear Admiral Sir William Sidney Smith, an exceptional intelligence officer, to take command of the small squadron of five of the line and two or three frigates then assembling at Messina. Sidney Smith arrived there on 21 April and from then until the middle of May Smith’s squadron was engaged assisting the Neapolitans: operations that included the capture of the island of Capri on 11 May, a successful action that was followed by the landing at Calabria of Major General John Stuart with between 4,800 – 5,200 men on the night of 30 June / 1 July.[96]

The Island of Capri, by William Wyllie

View of Calabria in the Straits of Messina, by William Wyllie

Major General John Stuart, landed with 4,800 at Calabria, 1 July 1806

Stuart’s forces routed 7,000 French troops in a sharp action on 4 July near the village of Maida, suffering only 45 killed and 280 wounded, but capturing or killing the majority of the French forces, perhaps capturing as many as 4,000.[97] Although one biographer considers the action largely the success of his subordinates, General Stuart was nevertheless promptly knighted and awarded a life pension of £1,000.[98] This minor success however could not change the strategic situation in Naples ,as Gaeta fell to the French on 18 July and the English were at last forced to withdraw to Sicily.[99]

The Naval War in the Baltic & the Capture of Copenhagen, 1807

William Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland, Prime Minister 1807-1809, copy by John Powell of Joshua Reynold, c. 1782

George Canning, Secretary for War

By the summer of 1806 Napoleon’s naval potential was 45 French and Spanish warships spread across his Atlantic and Mediterranean ports. He expected another six Dutch and eight French warships to be ready soon from Antwerp, Flushing and Texel, plus perhaps another 11 from Sweden and 16 from Denmark, not to mention the 20 Russian warships at Reval and Kronstadt. The Baltic therefore was liable to become a critical theatre of the war, at precisely the time Napoleon would be campaigning in Germany. To pre-empt Napoleon’s movements in this direction Secretary for War George Canning and Foreign Secretary Viscount Castlereagh determined on 19 July to present an ultimatum to the Danes insisting that they hand over their fleet to the British. When this was predictably rejected an expedition was organized to land troops as part of a combined naval bombardment of Copenhagen with the goal of capturing the Danish fleet and stores.[100]

Robert Stewart, Lord Castlereagh, the 2nd Marquess of Londonderry, Foreign Secretary in Cavendish’s government

The Bombardment of Copenhagen

Admiral James Gambier, Baron Gambier, by William Beechey & William Holl, print c. 1833

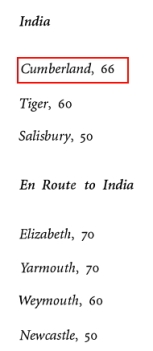

The Admiralty wasted no time and Admiral James Gambier’s fleet of 22 warships, with 19,000 troops under Lieutenant General Lord Cathcart, sailed from Yarmouth on 26 July.[101] Gambier’s Captain of the Fleet, despite his court martial in March having concluded only the month prior, was, perhaps unsurprisingly, Home Popham.[102] The Dutch capital was defended in the same fashion as it had been during Nelson’s attack in 1801: 174 guns, more than two dozen mortars, plus 5,500 soldiers, another 4,000 sailors and 3,600 militia, the dismasted Mars (64), five mobile frigates, and 30 gunboats.[103] The rest of the Danish fleet, about 30 warships of various sizes, were to be blockaded inside the port of Copenhagen itself.

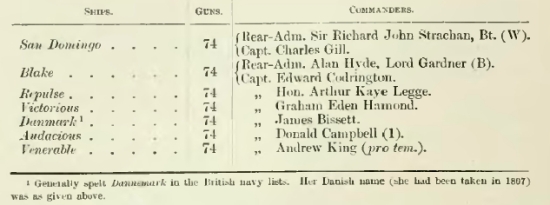

Admiral Gambier’s fleet for the Copenhagen expedition

William Cathcart, Earl Cathcart, 1807, by John Hoppner and Henry Meyer

Landings commenced on 16 August, the Danish gunboats offered a token resistance on the 17th, and Gambier established his blockade line on the 18th.[104] A small flotilla of bomb vessels, commanded by Captain Peter Puget in the Goliath (74), prepared to attack the Danish defences, but on the morning of the 23rd the Danes launched a spoiling attack with their gunboats, successfully driving off the British, yet the Danes were in turn driven back by cannon fire from the English beachhead.[105]

Speedwell-type 142 ton sloop of 12 guns, c. 1752

Captain Puget’s bomb flotilla, plus the third-rate Goliath during the attack on 23 August 1807

A 1790 pattern 123-ton shallow draft 12 cannon gunboat of the bomb vessel-type

Repeated sorties to disrupt the British siege works on the 25th, 26th and 27th failed, but the effort was renewed on the 31st. On 1 September the British issued a proclamation to General Peyman commanding the Copenhagen garrison to surrender, but he refused and thus Copenhagen was bombarded with a terrific fire the following evening. The cannonade continued for 48 hours, Peyman finally requesting terms on the 5th and then capitulating on the 7th.[106]

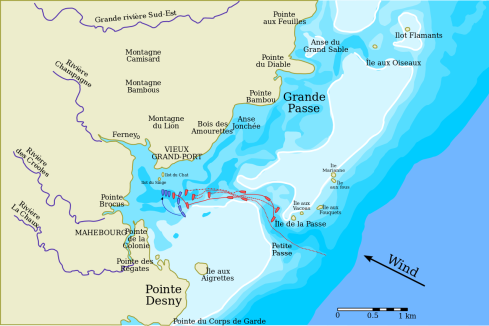

Views of the Bombardment of Copenhagen, by Christian William Eckersberg, c. 1807, Thomas Buttersworth, c. 1813, and 2-5 September 1807 by Jean Laurent Rugendas

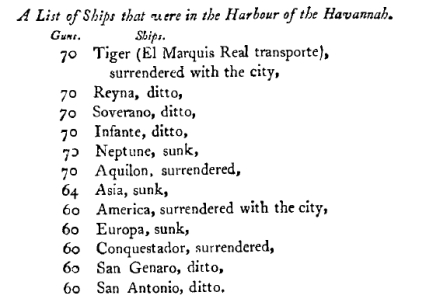

The entire Danish fleet at Copenhagen was captured (of which four battleships were eventually added to the Royal Navy), including the various gunboats – as many as 52 smaller vessels and 15 frigates – plus 20,000 tons of naval stores. Gambier returned the fleet to England on October 21st, and was promptly elevated to the peerage as Baron Gambier. The cost for the British was primarily diplomatic, as they had of course attacked what had been a neutral country, thus handing Napoleon a propaganda coup if nothing else. The immediate consequence was to prevent Napoleon from gaining the Danish fleet in the aftermath of Tilsit.[107]

List of Danish warships surrendered at Copenhagen

Breaking up Danish naval stores and ship construction

The Dardanelles and Alexandria, February – March 1807

The Ottoman Empire was also in play during 1806/7, as the Sultan was gravitating towards Napoleon’s sphere. On 2 November 1806 Collingwood despatched Rear Admiral Thomas Louis in Canopus (80), along with Thunderer (74), Standard (64), Active (38) and Nautilus (18) to reconnoitre the Dardanelles, where they arrived and anchored at Tenedos on the 21st. During December Rear Admiral Louis had recourse to collect the British ambassador who had separately departed Constantinople aboard the Endymion, a prudent decision given the deterioration of relations with the Sultan.[108]

Sketch of the site of Troy, looking towards Tenedos, & Pacha’s Point lighthouse at Gallipoli, July-October 1853 by George Mends

On 22 November the British government sent orders to Collingwood to despatch an expeditionary squadron to anchor off Constantinople and pressure the Porte not to intervene against British interests (the Ottoman Empire declared war against Russia in December 1806).[109] Collingwood did not receive these orders until 12 January 1807, but upon receipt immediately determined upon Vice Admiral Duckworth for the mission. Duckworth departed on the 15th aboard the Royal George (100). His orders were to consult with Mr. Arbuthnot, the British ambassador who was then waiting with Rear Admiral Louis at Tenedos and, if the situation called for it, to sail to Constantinople and induce the Turks to hand over their fleet.[110]

Rear Admiral Thomas Louis of the White, d. 17 May 1807

Vice Admiral Duckworth, by Giovanni Vendramini, December 1809

The Dardanelles expeditionary force

2,278-ton 100-gun first rate Queen Charlotte (1789), the same generation as HMS Royal George (1788

From the start Duckworth was concerned about the operation and could only have become more worried when at 9 pm on 14 February a fire broke out aboard HMS Ajax, quickly got out of hand, causing the ship to drift ashore at Tenedos where it exploded at 5 am the following morning, with the loss of 252 out of 633 officers and men.[111]

1811 chart of the Dardanelles, reproduced in William Laird Clowes, History of the Royal Navy, volume V, p. 223

Duckworth’s anchorage at the entrance of the Dardanelles, 14 February 1807, by Nicholas Pocock

Despite this setback Duckworth was on the move again on the morning of the 19th, his force divided into two divisions, with Rear Admiral Sir Sidney Smith commanding the Pompee, Thunderer, Standard and Active, and carrying orders to defeat the Turkish squadron (one 64, one 40, two 36s, one 32, one 22 corvette, one 18 corvette and two 10 corvettes, two brigs and three gunboats) at Point Pesquies, modern Nara Burnu, if they attempted to intervene.[112]

Rear Admiral Sir William Sidney Smith

The Turkish positions were largely obsolete medieval fortifications and were little threat so long as the British were able to suppress them with naval cannonade. The Turks started firing as soon as Duckworth entered the peninsula, the British suffering six killed and 51 wounded. At about 10 am the Turkish squadron deployed to engage Duckworth, but they were immediately countered by Sidney Smith, whose division anchored alongside the Turkish line and rapidly reduced them – within thirty minutes all but two of the Turkish warships had surrendered.

Thomas Whitcombe’s paintings of Duckworth’s action on 19 February 1807.

Sidney Smith reduces the Turkish fleet.

The Turkish vessels were immediately burned, while landing parties of seamen and Royal Marines secured the Point Pesquies redoubt and spiked the guns at the cost of four killed and 26 wounded.[113] Sidney Smith detached Active as a rear guard and at 5 pm his division hauled in their anchors, setting sail to rejoin Duckworth’s division.

The whole fleet was eight miles from Constantinople by 8 pm on 20 February. The next morning the Endymion was despatched to the city to deliver Mr. Arbuthnot’s declaration – including a 36 hour ultimatum demanding the surrender of the remaining Turkish fleet and its stores.[114] The Porte simply ignored the attempt to deliver the ultimatum, and despite expiration of the original timeline no consequences were imposed. Ambassador Arbuthnot fell sick on the 22nd and the Turks continued to ignore Duckworth’s demands. The essential dilemma for Duckworth was that his goal ultimately was to arrange a peace settlement, not bombard Constantinople, and although there can be no doubt that Duckworth was a fighting Admiral he was perhaps deficient as a diplomat and negotiator.

Nara Burnu today, & modern topography of the straits

Lacking a dedicated landing force it was not clear how Duckworth could have convinced the Turks to concede.[115] At any rate, after a series of further shore skirmishes and failed efforts to force negotiations, on 1 March Duckworth gave up. He weighed anchor around 8:30 am and sailed back towards the Mediterranean where he arrived back at Point Pesquies, retrieved the Active at 5 pm on 2 March, and was underway at 7:30 am the next morning. That afternoon Duckworth was engaged by the Turkish redoubt at Point Pesquies, including 800 lb shot from medieval cannons, and it was not until 11:35 pm that the entire fleet had passed the batteries and exited the Dardanelles, the squadron having sustained a further 26 killed and 130 wounded during this withdrawal.[116] It seems evident that the Dardanelles operation, much like the Gallipoli campaign a century later, should have been delayed until a landing force had been assembled – perhaps as little as a month could have made the difference.[117]

Lithograph of Alexandria, c. 1847 by William Delamotte and Charles Chabot

The disjointed planning efforts of the Grenville ministry were demonstrated thoroughly when Duckworth arrived back in the Mediterranean and was shortly thereafter joined by eight Russian battleships under Vice Admiral Seniavine, who was eager to try again, an endeavour Duckworth notably refused to attempt. Worse, the landing force Duckworth actually needed had been arranged and despatched on 6 March in 33 transports, but was not destined for the Dardanelles: escorted by Captain Benjamin Hallowell in the Tigre (74), with the Apollo (38) and the Wizard (16), 5,000 troops under Major General Fraser had departed from Messina bound for Alexandria. The task force arrived off Egypt between the 15th and the 19th, with landings taking place on the 17th and the 18th. Aboukir castle was stormed on the 20th and Alexandria surrendered on the 21st. Duckworth arrived on the 22nd. Major General Fraser attempted to take Rosetta by assault but was repulsed with the loss of 400 men – including the Major General himself.[118]

1 April 1809, HMS Mercury (28), Captain Henry Duncan, cut out the French gunboat Leda from Rovigno harbour, south west of Trieste, by William John Huggins

The operation lingered on until September when the entire force was withdrawn. Duckworth had already departed in the Royal George for England, leaving behind Rear Admiral Sir Thomas Louis who died aboard the Canopus on 17 May. The Russians, however, captured Lemnos and Tenedos, defeating a Turkish fleet off Lemnos, until peace was settled by the Treaty of Tilsit and Vice Admiral Seniavine sailed for the strait of Gibraltar, destined, he hoped, for the Baltic. Later in 1808 Collingwood was called away to attempt with diplomacy what Duckworth had failed to achieve with battleships, and successfully convinced the Turks to abandon the war. The Ottoman Empire signed a peace treaty in January 1809.[119]

The 1807 operations against Denmark and Turkey created new enemies. Worse, Napoleon knocked Prussia and Russia out of the war at the battles of Jena and Friedland with the result, as we have seen, of the signing of the treaty of Tilsit on 7 July. Proposed Royal Navy operations against the Spanish colonies in the Caribbean did not materialize, in part the result of the revolt against Napoleon in Spain, leaving the 18,000 men and more than 80 warships garrisoning Jamaica, plus the Leeward and Windward Islands, with little to do. In December Rear Admiral Alexander Cochrane did however capture the Danish Caribbean colonies of St. Croix, St. Thomas and St. Johns (see above).[120]

The Baltic Campaign, 1808

Napoleon’s efforts to diminish Britain’s trade through privateering resulted in the French taking 559 British merchants in 1807.[121] With the Russian declaration of hostilities on 31 October 1807 the principal theatre of operations for 1808 transitioned to the Baltic, where Britain’s Swedish ally was at risk of attack from the Russians – potentially jeopardizing Britain’s valuable Scandinavian trade.[122]

Henry Phipps, Baron Mulgrave, First Lord of the Admiralty in Portland’s ministry, 1807-10, engraving by Charles Turner from 1807 drawing by Sir Thomas Lawrence, published November 1808

First Lord of the Admiralty the Baron Mulgrave selected Vice Admiral James Saumarez for the Baltic mission. Saumarez was to take a fleet, 12 or 13 sail of the line, and supported by Rear Admirals Hood and Keats, destroy the Russian fleet at Cronstadt.[123] Saumarez and Lt. General Sir John Moore were in the course of preparing this expedition when the Czar pre-empted them by invading Finland.[124]

Vice Admiral James Saumarez, copy of Thomas Phillips portrait, made by Edwin Williams in 1862

Lieutenant General Sir John Moore, by Thomas Lawrence, engraving by Charles Turner, drawn c. 1805, published April 1809

Saumarez departed with Hood on 21 March 1808 for Gothenburg where he would rendezvous with Captain George Parker in the Stately (64), the officer on station there, and then confer with the British envoy at Stockholm regarding the best measures for protecting Sweden from further Russian or French incursion.[125] Ultimately a force of 62 ships, including 16 line of battleships, plus frigates and transports, capable of delivering 10,000 men, was built up and employed blockading the Russians in harbour and protecting merchant trade.[126]

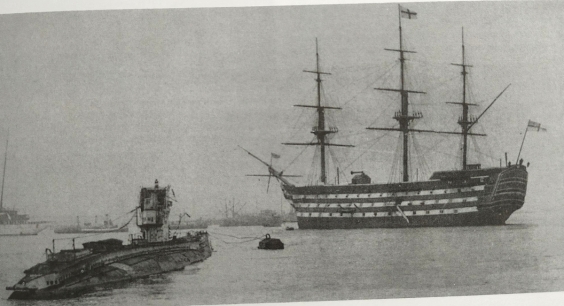

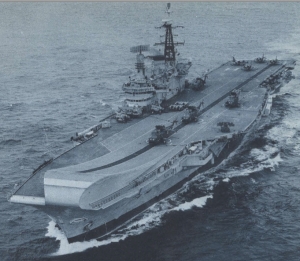

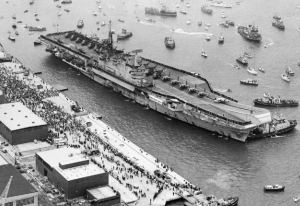

Vice Admiral Saumarez’s flagship during the Baltic campaign of 1808 was HMS Victory, rendered here off Belem Castle, by Thomas Buttersworth in 1797

Victory at the Portsmouth historic dockyard in 2020 & Crew composition.

A brief engagement occurred on 22 March when Captain Parker in the Stately with Captain Robert Campbell in the Nassau (64, ex Holstein captured at Copenhagen 1801), having sailed from Gothenburg on the 19th, engaged Denmark’s only remaining ship of the line, the 64 (or 74) gun Prinds Christian Frederik north of Zealand. After a two hour fight the Danish ship surrendered and ran aground. The crew was removed and the ship set afire afterwards.[127]

Normal trade protection and blockade actions continued until the Russians sortied on 25 August, intent on attacking Stockholm. The Royal Navy in the Baltic was by now divided into several components, and it was Rear Admiral Samuel Hood’s command that spotted the Russian fleet at sea off Hango on the 25th. Hood commanded a combined English and Swedish squadron, although a third of the Swedish seaman were incapacitated with scurvy and therefore of doubtful capacity.[128] Hood made to chase the Russians, who fled, until at 6:45 am on the 26th the Sevolod (or Sewolod, 74), appeared and engaged the British, no doubt hoping to delay them while the rest of the Russians escaped.

During this action the Implacable (74, Captain Byam Martin) and the Centaur (74, Captain William Webley; flag of Rear Admiral Hood), engaged the Sevolod at pistol shot, and by 8 am captured that ship, with six killed and 26 wounded on Implacable, and 48 killed and 80 wounded on the Sevolod. The approach of the rest of the Russian fleet convinced Hood to withdraw. The unmanned Sevolod crashed ashore at Roggersvick, and the Russians were attempting to float her when Hood returned with his two 74s and at 8 pm Captain Webley in the Centaur engaged the Sevolod close, the latter striking for the second time forty minutes later. Centaur had three killed and 27 wounded, the Sevolod 180 killed and wounded. The Russian warship was then burnt, all of which was action enough to convince the Russians not to attempt the crossing to Stockholm, and they were confined to their base at Roggersvik.[129]

To reduce this place Saumarez, on 30 August, arrived with Victory, Mars, Goliath and Africa and maintained the blockade of Roggersvik until October. Although plans were drawn up to launch a fireship attack against the Russian squadron, as was done at the Basque Roads the following year, it was later determined that the Russian harbour defences prevented any such action. Saumarez was compelled to depart with the arrival of winter, and the Russians returned thence to Cronstadt.[130]

James Saumarez’s squadron for the 1808 Baltic expedition

The Baltic squadron continued to intercept French and Danish privateers throughout 1809. On 11 May the Melpomene (38), Captain Peter Parker, located a Danish 6-gun cutter ashore at Huilbo, Jutland. Parker anchored, launched his boats, and then fired broadsides at the cutter until his boats arrived and completed the destruction, this handy operation completed at the cost of only six wounded. Four days later the 18-pdr frigate Tartar (32), under Captain Joseph Baker, chased ashore a small 4-gun privateer of 24 crew near Felixberg, Courland. The frigate’s boats were hoisted out and the diminutive Danish warship easily captured

Captain Peter Parker, by John Hoppner, c. 1808-10

On 7 July 1809 the Implacable (74, Captain Samuel Warren), Melpomene (38 – Parker), and the sloop Prometheus (18, Captain Thomas Forrest), while cruising off the coast of Finland, located a Russian gunboat flotilla of eight vessels at Porcola Point. Bellerophon (74) presently arrived and together 17 boats were assembled under Lieutenant Joseph Hawkey of Implacable, with 270 officers and men. The boat team waited until 9 pm and then rowed in under heavy fire and boarded the Russian flotilla at which point Lt. Hawkey was killed by grape shot, but Lt. Charles Allen took over command and completed the task of capturing the Russian gunboats, with 17 killed and 27 wounded, to the Russian’s 63 killed. A similar action was carried out on 25 July by 17 boats from the Princess Caroline (74), Minotaur (74),Cerberus (32) and the sloop Prometheus (18), against four Russian gunboats and a brig at Fredericksham, gulf of Finland. Once again the crew waited until the evening and then rowed into the anchorage and captured the Russian vessels, at cost of 9 killed and 46 wounded, the Russians losing 28 killed and 59 wounded (W. James, Naval History of Great Britain, vol. V, 1859, p. 38, 40-2).

N. C. Wyeth illustration

Although Sweden was protected for now, ultimately the Baltic campaign failed to prevent the Russians from annexing Finland at the Peace of Frederikshamn, 17 September 1809.[131] Saumarez did however effect the capture of the island of Anholt in May,[132] in addition to his sterling work protecting merchant traffic through the Great Belt strait: between June and December 1809 the Royal Navy escorted 2,210 merchants through those confined Danish waters without loss, however, a Norwegian convoy of 47 was taken by Danish Captain Lorentz Fisker with five brigs during a daring sortie in July 1810.[133] The British position in the Baltic was now tenuous as Sweden was then under Napoleon’s thumb, the Emperor having installed Marshal Bernadotte as monarch in October 1810.[134] He was soon induced to declare war against Britain, and did so in November.

The Peninsular Campaign, 1807 – 1809

The Iberian Campaign

On 18 October 1807 Napoleon despatched General Jean Junot, with 25,000 men, to secure French interests in Spain and prevent British intervention in Portugal. Within a month of crossing the Spanish frontier the French forces were built up to 75,000 in three corps.[135] Junot was soon ordered to secure Lisbon, lest the British intervene, which they were in fact preparing to do.

Rear Admiral Sir William Sidney Smith by Henry Heath, February 1808

The Tagus expedition, November 1807

Sidney Smith was despatched early in November 1807 with a squadron to the mouth of the Tagus, his flag after the Dardanelles and Egyptian operations now in the new Hibernia (120), [136]

HMS Hibernia (120), Sidney Smith’s flagship in 1807-1808

Lord Strangford, the British representative at Lisbon, departed to join Rear Admiral Smith, who was by mid-November blockading Portuguese merchant traffic. Going aboard the Confiance (20), Strangford sailed back to Lisbon on the 27th, under flag of truce, demanding that the Portuguese navy surrender – and if they did so, the blockade would be lifted. The Prince Regent Dom Joao accepted these terms, and on the 29th embarked aboard the Portuguese fleet with Queen Maria II and the rest of the royal family, not to mention the state treasury, for the voyage to Brazil.

Dom Joao, the Prince Regent, later John VI of Portugal, painted in 1803 by Domingos Sequeira

The Embarkation of the Portuguese Royal Family, 29 November 1807

Captain Sir Graham Moore, painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence in 1792

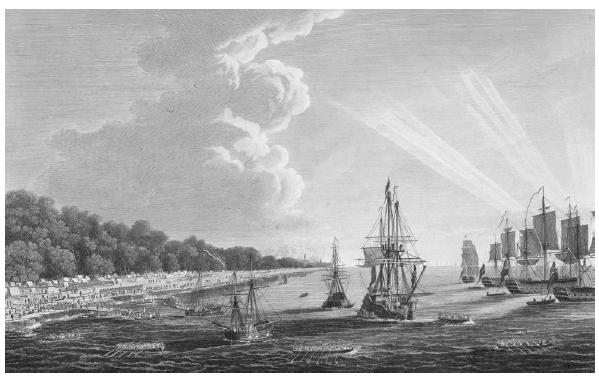

Rear Admiral Smith detached Captain Graham Moore’s squadron, including the Marlborough, London, Monarch and Bedford, as escort to Rio de Janeiro. The flight of the royal family was not a moment too soon, as General Junot entered Lisbon on 30 November.[137] The Portuguese fleet of eight of the line and its frigates was turned over to the Royal Navy. As Herbert Richmond observed this operation, in conjunction with Copenhagen, put Napoleon’s net warship losses to no less than 25 capital ships.[138]

24 gun sixth rate circa 1740, & 22 gun sixth rate c. 1725

As an addendum to this series of events, it should be mentioned that after the British squadron arrived at Rio de Janeiro Captain James Yeo in the Confiance (22, 18-pdrs) was detached to sail to Paraguay where he had orders to consult with the governor there regarding the possibility of an attack upon Cayenne, capital of French Guiana. Yeo in fact landed a small contingent of 400 at Cayenne on 7 January 1809 and carried that place within five weeks despite it being garrisoned by 1,200 men and 200 guns. As a result Yeo received the favours of the prince regent of Portugal and was then knighted by George III on 21 June 1810.[139]

N. C. Wyeth illustration for Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island

Captain Sir James Yeo captures Cayenne, January 1809: View of Constable Rocks off Cayenne, by T. Conder and Joseph Johnson, 1 December 1791

The other purpose of Rear Admiral Smith off the Portuguese coast was to intercept Vice Admiral Seniavine’s squadron that as we have seen was making for the Baltic after the collapse of the Dardanelles and Alexandrian expeditions, and who Britain was now at war with following the Russian declaration of 31 October. Late in 1807 Smith was reinforced by the arrival of Commodore Peter Halkett in the Ganges (74) who had with him also the Defence (74), Alfred (74) the Ruby (64) and the Agamemnon (64), sailing from Portsmouth on 6 December.[140] While Smith was escorting the Portuguese royals Vice Admiral Seniavine slipped into the Tagus and was there when Smith returned to cruise off Lisbon early in 1808.

Medal commemorating the capture of Cayenne, 1809

The Spanish however were engaged in diplomacy with their British counterparts and on 4 July arranged a cessation of hostilities. Rear Admiral Smith maintained his blockade off the Tagus while minor operations continued along the Portuguese coast. Admiral Sir Charles Cotton, who replaced Smith in charge of the Tagus blockade, on September 3rd signed a surrender agreement with Vice Admiral Seniavine by which the Russians conceded to hand over their warships to the British until relations could be normalized – the crews were repatriated.[141]

Admiral Sir Charles Cotton, c. 1812 by James Ramsay and Henry Meyer

Russian squadron surrendered at the Tagus, 3 September 1808

The situation in Spain had been evolving rapidly since the summer of 1808. In May a Spanish rebellion against French rule broke out in Madrid, and in July 22,000 men of the occupation army were forced to surrender at Baylen. This disaster isolated Junot in Portugal. In June Foreign Secretary Canning stated his intention to support the Portuguese by landing British troops.[142] There were several contingents that could be utilized for this purpose: 9,000 men in Ireland, under Sir Arthur Wellesley, who had been gathering to relieve the South American expedition, and Sir John Moore’s 10,000 with Saumarez in the Baltic, plus another 10,000 Spanish troops who were operating with Rear Admiral Keats against the Danish.[143]

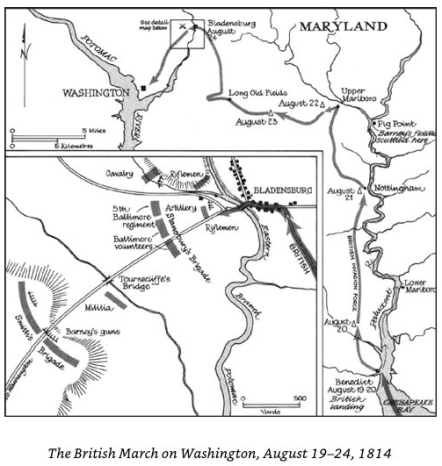

Jean-Andoche Junot, Napoleon’s general in Portugal during 1807-8, by Vincent-Nicolas Raverat, c. 1834