Osprey Mark IV conversion, photographed at the Aircraft Armament Experimental Establishment, Martlesham Heath. This advanced Osprey had been designed to fulfill Air Ministry Specification 26/35, naval fighter/reconnaissance.

The Hawker Osprey was the naval version of the Hawker Hart/Hind: a two seater light bomber designed by the Air Ministry for Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy, to complement the Hawker Nimrod, the naval version of the Hawker Hornet/Fury single seat fighter. Considered the most important RAF acquisition between 1918 and 1936, the Hart and its numerous variants defined the interwar period, becoming the Air Ministry’s single most widely produced aircraft. The Hart and Hornet had been designed to take advantage of the improvements in engine technology that had occurred ten years after the First World War, notably, the newly designed Rolls-Royce Kestrel V-12 inline of 1925.

The Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Air Force had been formed in April 1924, effectively recreating the carrier wing of the Royal Naval Air Service, as it had existed at the time of its dissolution, six years prior, in April 1918. Under the new compromise, the Admiralty would control the FAA operationally, with the Navy and Royal Marines providing the majority of pilots, as well as all observers, gunners and wireless operators, and the Admiralty delivering its aircraft requirements to the Air Ministry.[i] In October 1924, the FAA was composed of 18 Flights, totaling 128 aircraft: Blackburn Blackburns (torpedo bomber), Avro Bisons (bomber/spotter) and Fairey Flycatchers (fighter), in addition to seaplanes.[ii] Although the wartime giant Sopwith corporation had gone under in the 1920s, the legacy of the 1 ½ Strutter ultimately lived on in the form of the Osprey.

Wing Commander Richard Bell Davies takes off from HMS Argus in his Sopwith 1 1/2 Strutter in October 1918. The Hawker Osprey filled the same role, functioning as a general purpose, two seat, carrier scout-bomber.

The single seat Fairey Flycatcher fighter, seen here fitted with floats at the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment, Felixstowe.

The Avro Bison, a four man gunfire spotter and bomber, replaced by the Osprey in the 1930s.

Restored Hawker Demon today.

The Hart was the fighter-bomber variant of the two seater Demon, itself a modified Hornet/Fury/Nimrod, which, for the Hart and Osprey, effectively meant exchanging the second Vickers gun in the fighter, for the bombsight and gear of the light-bomber. Indeed, the Hart had been designed to fill the role of Single-Engined Day Bomber (SEDB), Specification 12/26, for which it competed against the Avro Antelope and Fairey Fox II in 1928.[iii] This was the year that the Fleet Air Arm was due to receive new aircraft, First Sea Lord David Beatty having delayed the upgrades from the 1926-27 Naval Estimate for reasons of economy.[iv] The Hawker line would go on, in 1933, to replace the Flycatcher fighter with the Hawker Nimrod, the naval version of the twin Vickers gunned Fury single-seater. The Hawker Horsley had also been adopted for the 1928 estimate as a torpedo bomber, a role likewise considered for Hawker Harrier as per Specification 23/25 in February 1927.[v]

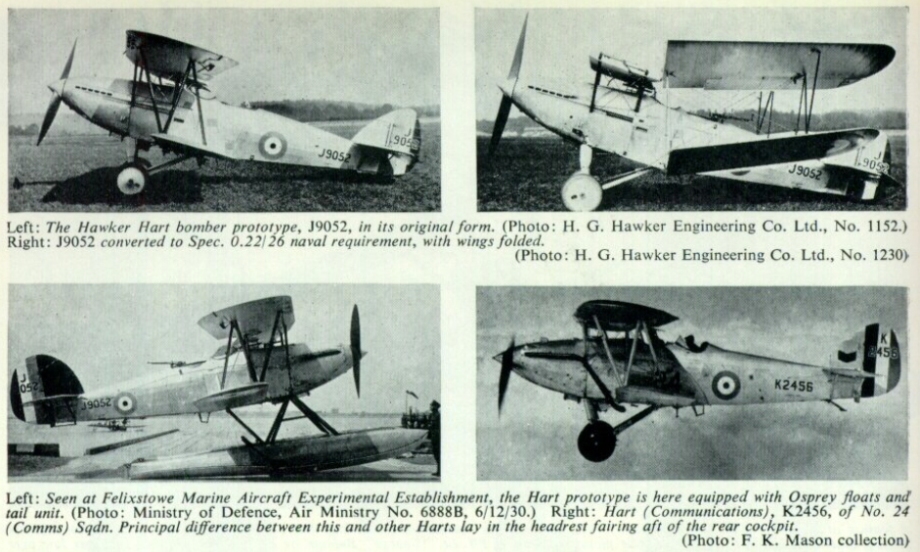

The Hawker Hart prototype, showing the Osprey variants- with folding wings (top right) and floats (bottom left). The Osprey had been designed to fulfill the RAF’s 21/34 Specification for a fleet spotter and reconnaissance aircraft.

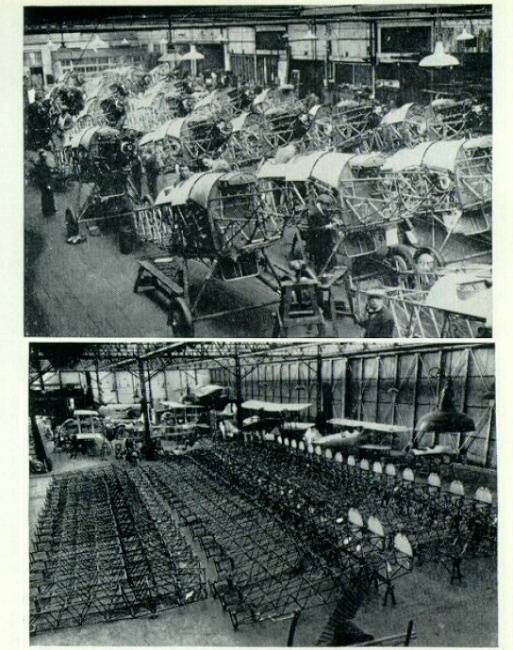

Hawker Harts being manufactured at the Hawker facility, Kingston, (top) and by Vickers Ltd., by sub-contract.

Late model Rolls-Royce Kestrel XVI, the 21-litre 1,295 cu V12 water-cooled inline was first developed as an Air Ministry project to replicate the single-block architecture of the 18-litre American D-12 Curtiss during 1925-6. Kestrel variants could generate between 500 (IB model) and 600 hp (V model), and as much as 750 horsepower in the supercharged Peregrine derivative. This was the direct predecessor of the legendary 27-litre 1,650 cu (1,100 hp) P.V.12 (Merlin), utilized in the Hawker Hurricane, Supermarine Spitfire and North American Mustang.

The Hart/Osprey was equipped with a Mk. III Lewis gun and a single .303 Mk. II Vickers gun with C. C. synchronizing gear, which allowed the machine gun to be fired directly through the aircraft propeller. From The Armament of British Aircraft 1909 – 1939, by H. F. King, p. 235.

Firing the Hart’s Vickers gun.

The Hawker style Scarff ring for the observer’s Lewis gun.

Part of the naval adaptations, other than folding wings and floats in the seaplane conversion, was the added Kiddle-Lux floatation bags attached to the upper plane wings.

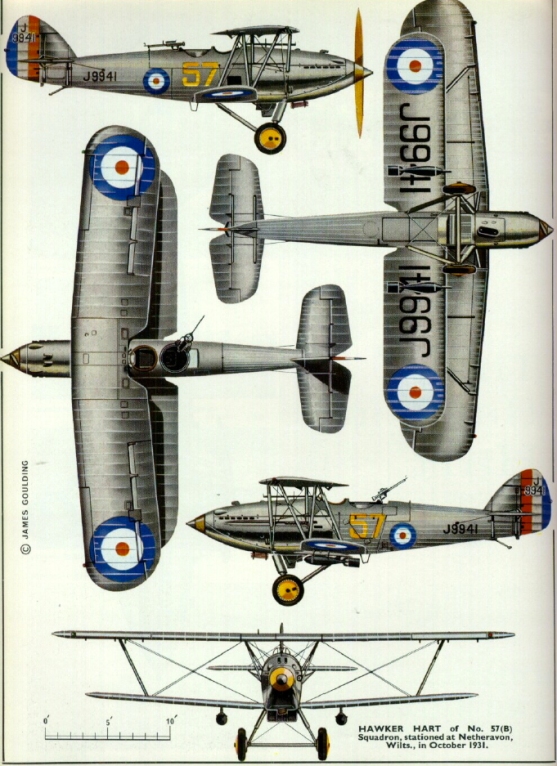

Line drawing of Hawker Hart by James Goulding, from Francis Mason’s Profile Publications volume 57.

Two seater Hawker Demon with Osprey seaplane. The Demon was a two seat fighter variant of the Hart/Fury designed for the RAF. Note the seemingly interchangeable design.

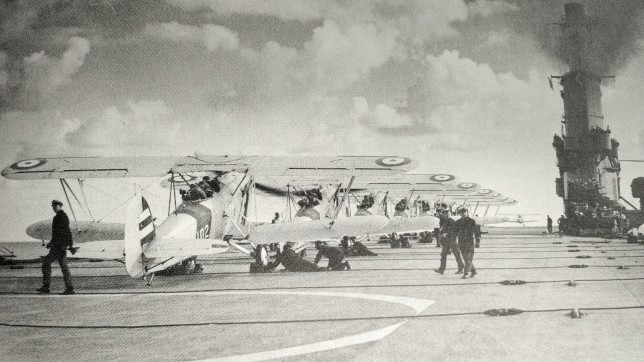

The Ospreys were first introduced to Flights No. 404 and 409 in November 1932, and No. 407 (seaplane) Flight had its Fairey IIIFs replaced by Ospreys for work with the cruisers of the Home Fleet. Ospreys also served in Flights 403, 406, 407, 443, 444, and 447. The Ospreys then joined Squadrons 800, 801, 802 and 803 when the FAA squadrons were re-formed in 1933.[x] Eventually the Squadrons were systematized, so that fighters (Nimrods) filled the 800s, FSR (Ospreys) the 810s and TSR (Horsleys) the 820s, each aircraft squadron colour-coded to the ship it was aboard: red for Courageous, yellow for Glorious, green for Eagle and black for Hermes.[xi] At the beginning of 1936 there were three Ospreys aboard Courageous, three aboard Furious, six on Eagle, three on Glorious, while there were another 34 seaplanes and other aircraft aboard 29 Royal Navy warships (144 aircraft in the entire FAA).[xii] Late generation Ospreys were still aboard HMS Ark Royal in 1939, when they were replaced by Blackburn Skua fighter/dive-bombers.

Hawker Ospreys from No. 800 Squadron aboard HMS Ark Royal shortly before September 1939, from British Naval Aviation by Ray Sturtivant, p. 27

In sum, 132 Ospreys served with the Fleet Air Arm, some ending their careers as seaplanes, having worked aboard the cruisers of the Royal Navy, others as trainer aircraft during the Second World War.

Ospreys conducting a night sortie aboard HMS Courageous in 1935, from Hugh Popham, Into Wind, p. 112

Captain Richard Bell Davies, who returned to the Royal Navy after the formation of the RAF, was critical of the Osprey only in terms of its suitability as a seaplane: he believed a slower, more robust and specialized, aircraft was required.[xiii] Indeed, it was during the 1930s, as wartime learning began to be forgotten, and radical technological developments accelerated, that the Admiralty attempted to simplify its requirements, down to essentially two airplanes: Torpedo, Spotter, Reconnaissance (TSR), and fighter/dive-bomber, plus seaplanes, thus losing the pure naval fighter role.[xiv] Whereas technical homogeneity during the disarmament period of the decade following 1918, and Air Ministry control of production, meant that invariably the FAA was going to have to make due with imperfect aircraft, the excellence of the Hawker design meant relative success in terms of roles: single seat fighter (Fairey Flycatcher, then Hawker Nimrod), two seat bomber/spotter/reconnaissance + seaplane (Hawker Osprey), torpedo bomber (Horsley): in effect, Hawker aircraft had become the entire RAF, and indeed most of the FAA, so far as single engine aircraft was concerned. In this regard Sydney Camm had come close to achieving the dream of efficiency sought by defence planners ever since, that is, the production of a single aircraft that, with slight modification, could fulfill every role.

Hawker Osprey seaplane aboard cruiser HMS Enterprise off Palestine in 1936.

Osprey Mk3 launching from HMS Sussex.

Ultimately, the Hart and Osprey, designed ten years after the First World War, were representative of the last decade of inter-service cooperation before the defence upheavals of the 1930s. Although in 1928 the Fleet Air Arm was still controlled by the RAF, responsibly was shared with the Royal Navy through the arrangement that became known as dual control.[xv] This system was maintained, although its existence in terms of utility for the Navy was doomed in so far as the FAA officers, holding RAF rank, were unlikely to advance beyond flight lieutenants: this was at least partly why the Squadrons were formed in 1933, to provide billets for 16 Squadron rank officers.[xvi] The history of the FAA has perhaps never been more controversial than it was during the third decade of the 20th century. Despite the administrative conflict, the second decade had left the FAA in good condition, concluding with the development of the Hawker Hart and Osprey, thus beginning the 1930s on a hopeful note.

Hawker Osprey Mark I flying above HMS Eagle,

Ospreys had been hunted to extinction in Britain by 1916, however, Scandinavian Ospreys recolonized Scotland starting in 1954. A joint English Nature and Scottish Natural Heritage project successfully reintroduced the Osprey to the England Midlands, at the beginning of the 21st century, starting at Rutland was reintroduced to England in 2001.

Rutland Osprey #30 (female), seen here in 2015; ZeroF the descendant of Osprey #09 (male), below.

[i] Bill Finnis, The History of the Fleet Air Arm: From Kites to Carriers (Longden Road, Shrewsbury: Airlife Publishing Ltd., 2000)., p. 26

[ii] Reginald Longstaff, The Fleet Air Arm: A Pictorial History (London: Robert Hale Ltd., 1981)., p. 93

[iii] H. F. King, Armament of British Aircraft, 1909-1939 (London: Putnam & Company Limited, 1971)., p. 235

[iv] Stephen Roskill, Admiral of the Fleet Earl Beatty: The Last Naval Hero (New York: Antheneum, 1981)., p. 355

[v] King, Armament of British Aircraft, 1909-1939., p. 229, 232

[vi] Francis Mason, The Hawker Hart, Profile Publications 57 (London: Profile Publications Ltd., n.d.)., p. 3

[vii] Ibid., p. 4

[viii] Kev Darling, Fleet Air Arm Carrier War: The History of British Naval Aviation (Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Aviation, 2009)., p. 329 – 30; King, Armament of British Aircraft, 1909-1939., p. 237

[ix] Darling, Fleet Air Arm Carrier War: The History of British Naval Aviation., p. 334

[x] Longstaff, The Fleet Air Arm: A Pictorial History., p. 100

[xi] Ibid., p. 101

[xii] Ibid., p. 102

[xiii] Richard Bell Davies, Sailor in the Air: The Memoirs of the World’s First Carrier Pilot (Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Seaforth Publishing, 2008)., p. 224

[xiv] Geoffrey Till, Air Power and the Royal Navy, 1914-1945, A Historical Survey (London: Jane’s Publishing Company, 1979)., p. 103; Hugh Popham, Into Wind (Pitman Press, Bath: Hamish Hamilton Ltd., 1969)., p. 110

[xv] Bryan Ranft, ed., The Beatty Papers: Volume II, 1916-1927, vol. 2, 2 vols., Navy Records Society 132 (Brookfield, Vermont: Ashgate Publishing Company, 1993)., p. 228

[xvi] Eric Grove, The Royal Navy since 1815 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005)., p. 174