Admiral Sir Charles Middleton, the Seven Years’ War, and Naval Administration

HMS Barham presentation badge in 1914.

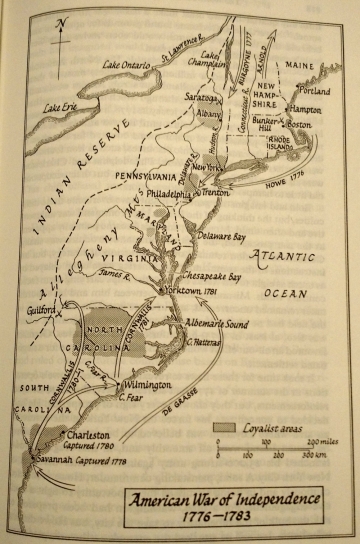

The Royal Navy career of Charles Middleton spanned three wars, from the Seven Years’ War, to the American Revolution, through the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. During the first of these, Captain Middleton was engaged in trade protection and anti-privateering duty in the Leeward Islands. The future Comptroller of the Navy, then a lowly frigate commander, sailing in the 28 gun HMS Emerald, spent four years countering French commerce privateers. Middleton was considered somewhat of a disciplinarian and social climber, but also a promising administrator in a far-flung but crucial colonial posting in the Caribbean during the Seven Years’ War. Middleton’s early career has been described as a typical RN officer’s career.[i]

The Right Honourable Sir Charles Middleton, 1st Baron Barham, Admiral of the Red, engraving by Marie Anne Bourlier, 12 October 1809, from a drawing by John Downman.

This post examines Admiral Charles Middleton’s career and achievements during the early phase, primarily concerning Captain Middleton’s role as a frigate commander during the Seven Years’ War, leading up to his appointment as Comptroller of the Navy in August 1778.

After the Seven Years’ War, Middleton seemed to have fulfilled his duty, and was prepared to retire.[ii] Fate, as it would have it, ensured that Middleton would yet return to the centres of power and play an unexpected, but decisive, role in the Royal Navy’s history. After his service in the Caribbean as a frigate commander and station administrator, Middleton went on to become a reformer and modernizer during the American Revolution, as Comptroller of the Navy. Rear-Admiral Middleton, raised to the peerage as Lord Barham, returned to power as Senior Naval Lord and eventually First Lord of the Admiralty at the time of Trafalgar in 1805.

London in 1751 by Thomas Bowles

Career of Charles Middleton until 1778

The Navy

Charles Middleton was born at Leith, Edinburgh, on 14 October 1726, the second son of Robert Middleton and Helen Dundas. Helen was the great-granddaughter of Robert Dundas, Lord Arniston, while Robert, the father, was a descendant of Alexander Middleton, the brother of John, the Earl Middleton, and made his living as a customs official in Bo’ness, West Lothian, Scotland. Charles Middleton joined the Navy at a young age, credited with service aboard the merchantman Loyal June (1738-41), starting when he was eleven- although this could have been a paper assignment only, as was often the case with young officers. Middleton joined his first warship, prophetically, HMS Sandwich (90), in April 1741 at the age of 14, and shortly afterward he followed its Captain, Mead, to the Duke (90), then joined the 20 gun frigate Flamborough under Captain Joseph Hamar on 21 November 1741, for service in North America and the West Indies.

Cape Corso fortress, Gold Coast, as it appeared in 1745, not long before Lt. Charles Middleton, while serving aboard HMS Chesterfield, was stranded there by mutineers in October 1748,

Just shy of four years of apprenticeship as a captain’s servant, midshipman and master’s mate aboard HMS Flamborough, and only ten days before his 19th birthday, Middleton passed his Lieutenant’s examination on 4 October 1745, and, the following month, was appointed to the 5th rate HMS Chesterfield (40), patrolling the channel and the coast of Sierra Leone.[iii] Middleton, 22 years old, was there in 1748, when on 15 October, at the notorious slave trading site, the Cape Corso fortress in Ghana, Middleton, along with the Chesterfield’s Captain (O’Brien Dudley), Master, 2nd Lieutenant, purser, surgeon, and 11 other men, were stranded by a mutiny amongst the ship’s crew and remaining officers. The mutineers were led by a buccaneering carpenter’s mate named John Place, with help from the supposedly drunken 1st Lieutenant, Samuel Couchman (neither of whom survived the conclusion of the court martial that was to follow). The loyal boatswain retook the ship and arrested the mutineers. The boatswain was able to bring the Chesterfield to English Harbour, in Antiqua, where it was reunited with the stranded officers on 7 March 1749.[iv] Middleton and company aboard, now under Captain James Campbell, Chesterfield returned to England, and arrived at Spithead on 14 June 1749.

US President Barack Obama visits the former slave trading outpost at Cape Corso castle, Ghana, 11 July 2009, the site where Lt. Middleton first experienced the disreputable connection between Royal Navy seapower and the slave trade.

Middleton was put on half-pay and sent ashore the following month.[v] There he remained until transferred to a dockside assignment aboard HMS Culloden (74), in June 1752. Back on half-pay in November, he was subsequently transferred to what would become a familiar ship, HMS Anson (Captain Charles Holmes), a 4th rate, 60 gun ship of the line built in 1747; In January 1753, Middleton, 26 years old, was thus acting in the capacity of second lieutenant aboard a large ship of the line. Anson’s first lieutenant at this time was one Richard Kempenfelt, later Rear-Admiral Kempenfelt.[vi]

Aboard HMS Anson, the first lieutenant in 1755 was Richard Kempenfelt, later Rear-Admiral Kempenfelt as painted by Tilly Kettle in 1782, prior to his drowning aboard HMS Royal George on 29 August of that year, tragically, at least partly the result of the Middleton – Sandwich coppering method which produced electrolytic degradation on warship rivets. Middleton and Kempenfelt exchanged letters on the subject of signalling during 1779 – 1782.

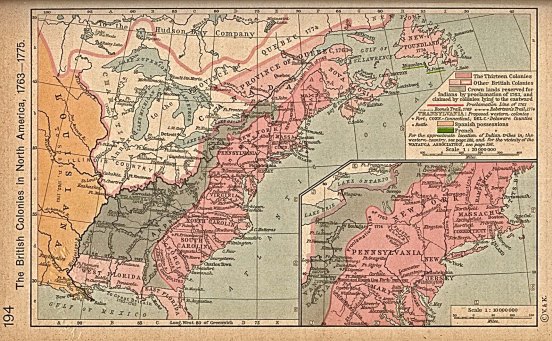

Middleton was briefly transferred to the Monarch (74), but was then back again aboard Anson in July 1754. Middleton succeeded Kempenfelt as 1st Lieutenant aboard Anson in January 1755. In March of that year Lt. Middleton was to be found recruiting sailors in the Bristol Channel, while aboard Princess Augusta.[vii] With Britain’s relations with France deteriorating, Middleton, aboard Anson (Captain Robert Man), was dispatched as part of Vice-Admiral Edward Boscawen’s fleet of 11 of the line to blockade the St. Lawrence, although, it being the spring of 1755, war had not yet been declared.[viii] Boscawen intercepted a detached French squadron of three and captured two 64 gun ships, Alcide and Lys, but missed a third, Dauphin Royal in fog off the Newfoundland Banks, June 8 – 9.[ix]

Vice-Admiral Edward Boscawen, who commanded the English squadron in which 28 year old Lt. Middleton served as first Lieutenant aboard HMS Anson (60), at the outbreak of the Seven Years War. Joshua Reynolds, 1824.

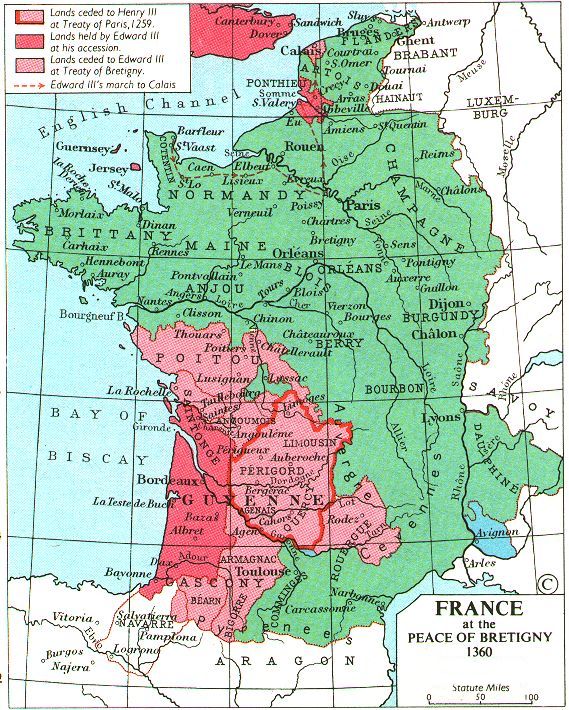

Admiral Boscawen’s action against Admiral de le Motte’s separated squadron 8 June 1755. In the foreground, Captain Andrews aboard the Defiance (60), engages Lys (64) while Captain Richard Howe, commanding the Dunkirk (60) attacks Captain de Hocquart’s Alcide (64) in the distance. This is an artistic compression: Defiance, along with Fougueux, were sent to chase Lys which was actaully captured the next day. Lt. Charles Middleton, the XO, under the command of Captain Robert Man, was aboard Anson (60), one of Boscawen’s eleven warships.

HMS Defiance of 60 guns, 5th rate when built in 1744.

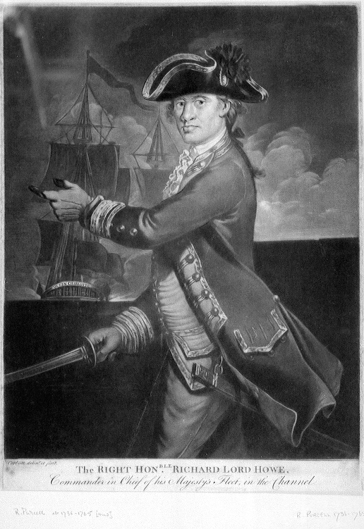

Admiral Lord Richard Howe, then Captain HMS Dunkirk, who fought together with Lt. Middleton as part of Boscawen’s fleet. Depicted here as C-in-C Channel Fleet, print made by James Whittle and Richard Holmes, 1794

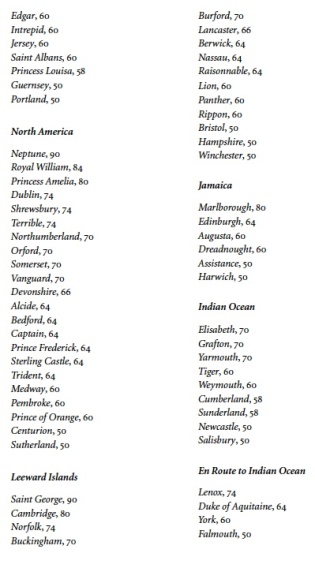

Royal Navy warships, as of June 1755, showing first Lt. Middleton’s appointment in red. From Jonathan Dull’s The French Navy and the Seven Years’ War.

Anson cruised off Louisbourg and Halifax, then returned to England in October 1755, and was eventually stationed in Portsmouth in March of 1756. Anson, along with Bristol (50) and Harwich (50) were now dispatched to the West Indies as part of the outbound convoy with 17 merchant ships, departing England on 27 April and arriving at St. John’s Road, Antigua on 12 June 1756. That same month, Minorca fell as a result of Admiral Byng’s failed relief attempt resulting from the battle of Port Mahon, 20 May 1756.

Commander RN, & The Seven Years’ War

During 1755-6, relations soured between England’s North American colonists and the French settlers in Canada and their Native American allies. A struggle for control of the Ohio River valley soon revealed the tenuous nature of the status quo peace. The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which had ended the War of Austrian Succession in 1748, was tested on a number of occasions, such as in 1755 when General Braddock’s force was ambushed. In India, Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Clive and the British East India Company continued their swashbuckling campaign of conquest, capturing Calcutta in January 1757, and winning the decisive battle at Plassey on 23 June 1757, further antagonizing French interests. War in Europe was renewed when Prussia invaded Saxony in 1756, prompting Austria to declare war on Frederick II in 1757. Britain declared war against France on 18 May of that year, pushing Prussia into coalition with Britain, for the Austrians, who counted amongst their allies Russia and Sweden, were also allied with Louis XV’s France.[x]

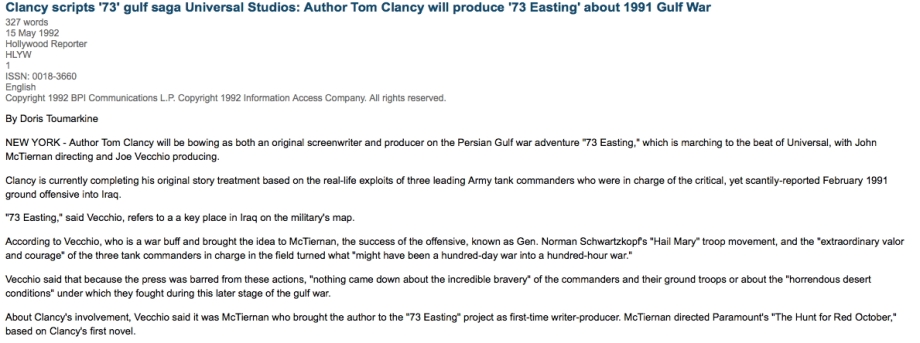

The World colonial situation prior to the Treaty of Paris, 1763 <http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/>

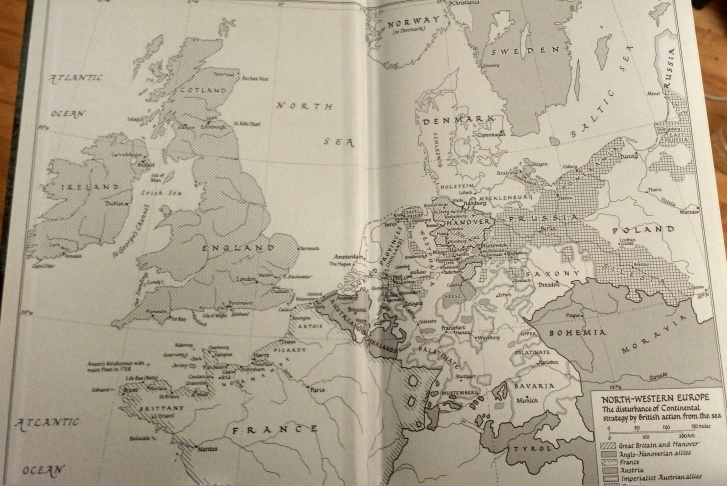

European political situation 1740 – 1757, maps.

Considering that the British monarchy originated from the electorate of Hannover, England joined Prussia and Portugal against the powerful coalition of France, Austria, Russia, Sweden, Poland, and after 1762, Spain. The war began with a series of British reversals, notably at Minorca, where Admiral Byng was unable to win the victory at Port Mahon, 20 May 1756, to the great detriment of his personal fortunes. France’s Louisbourg citadel, in present day Nova Scotia, however, was captured in July 1758. These tremendous events were followed by the capture of Quebec itself, after the victory at the Plains of Abraham on 13 September 1759. These military victories were accompanied by suitable naval victories, at Lagos, 18 – 19 August (Boscawen), and Quiberon Bay, 20 November (Hawke), during the victorious Annus Mirabilis.

French siege and capture of Fort St. Philip, Minorca, 29 July 1756. Admiral Byng’s defeat, on 20 May 1756, shortly after the outbreak of war, enabled the Marquis de la Galissonniere’s fleet to support the siege of the Mediterranean fortress.

Global conflict: The Seven Years’ War.

Frederick the Great won his major maneuver victories against overwhelming enemy coalition forces at Rossbach and Leuthen in November and December 1757, followed by the victory against Russia at Zorndorf in August 1758, dealing a serious repulse to the initial Grand Alliance war effort. As a result, Britain’s funding of the Prussian effort increased between 1757 and 1758 by nearly a factor of ten, to 1,860,000 pounds sterling. Frederick’s reversals against the Russians in 1759 at Kunersdorf led to Berlin’s capture, but Frederick maintained his defence against France and Austria, defeating the Austrians at Liegnitz in August, and again at Torgau in November, 1760. Britain, for its part, eventually abandoned the alliance, seeking a separate peace in 1762 to consolidate its colonial gains, a move that Frederick would not forget when Britain came looking for European allies during the American Revolutionary War.

First Lord of the Admiralty, Admiral of the Fleet, Lord George Anson as painted prior to 1748 by Thomas Hudson. The architect of Britain’s naval strategy during the Seven Years’ War, Anson was First Lord from 1751-56 and 1757-62.

Cartoon celebrating Captain Howe and Vice-Admiral Boscawen’s victories over the French in Canada, including the capture of Louisbourg in the summer of 1758.

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Edward Hawke, painted by Francis Cotes in 1768.

Admiral Sir Edward Hawke’s victory at Quiberon Bay, 20 November 1759, painted by Nicholas Pocock. This decisive battle by the Channel squadron prevented the planned invasion of England and Ireland, thus freeing Royal Navy forces for deployment to other theatres, including the Caribbean.

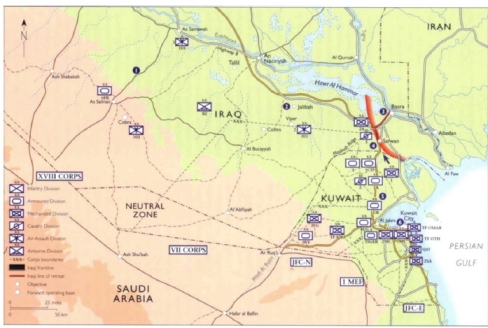

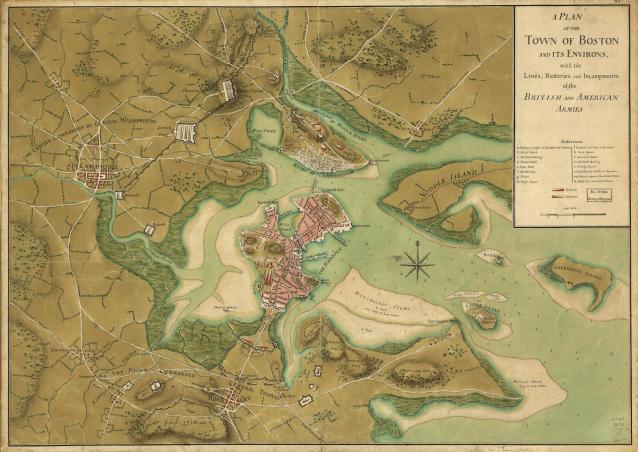

With the major struggle taking place in Canada and Europe, the Caribbean was at first a sideshow. The Royal Navy’s defence of its Caribbean trade had been arranged as a layered blockade and interdiction operation: the two station commanders, based at Jamaica and Antigua, were provided with small squadrons of 50 or 60 gun ships for blockading the enemy’s naval bases at St. Domingo (Spain) and Martinique (France). Heavy RN frigates of 30 to 40 guns sailed windward of Antigua and Barbados, seeking privateers. Lastly, 20 gun frigates and all lesser sloops, brigs and corvettes covered the inter-island communications, primarily around the Leeward Islands.[xi]

The Leeward Islands from NASA Terra satellite.

In 1756 the Jamaican station was under the command of Rear-Admiral George Townshend with three of the line and four frigates. The Leeward Island station was commanded by Rear-Admiral Frankland, with an additional three of the line and four or five frigates.[xii] When the Elder Pitt took power during his brief 1756-7 term under the Duke of Devonshire, he re-shuffled the Admiralty, using Boscawen to offset Anson, who at that time was the First Lord of the Admiralty, and doubled the size of the Caribbean fleets while appointing new commanders: Rear-Admiral Thomas Cotes, now with seven of the line and ten or so frigates, to Jamaica; and Commodore John Moore was ordered to the Leeward Islands with three of the line, two 50s, three 40s and five frigates.

Political situation in the Caribbean, 1756, from Sir Julian Corbett’s The Seven Years War. The islands of St. Lucia, Grenada and Dominica were at this time declared as neutrals under the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, although nominally under French control. The major French naval bases were at Guadeloupe and Martinique.

British Caribbean commands in June 1756, Lt. Middleton’s position in red.

Control of territory in Caribbean during 1756.

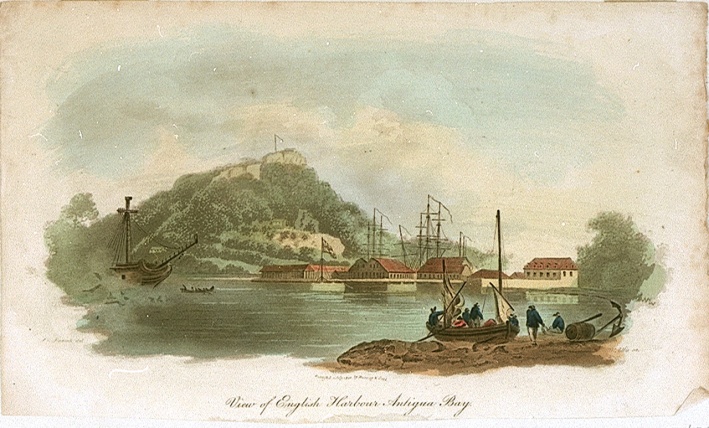

English Harbour, Antigua today.

It was with Commodore Moore, that Middleton, still aboard the Anson, was ordered to Antigua. Middleton, now thirty years old, continued aboard Anson until 26 February 1757 when he was promoted Commander, appointed to the sloop Speaker (12), to cruise in the Leeward Islands. There is some confusion regarding his command at this point, as he was simultaneously listed as commander of the Blandford, as acting captain (26 February to 28 March), while also having commanded of the sloop Saltash, briefly.[xiii]

Model of a 200 ton burden, 14 gun sloop, circa the 1740 pattern, similar to HMS Barbados commanded by Captain Middleton in 1758

Model of a 12 gun sloop on the 1752 pattern, ketch-rigged (note the mizzen mast and absence of a fore mast)

It is clear from the sources, however, that Commander Middleton’s position would involve dockyard work, and appreciating the administrative aspects of running a trade defence operation. In the event, Middleton was promoted Captain in July 1758, and took command of the newly constructed Barbados (12). Middleton’s role during this time was a small but critical part of the Admiralty’s vast world system: based at English Harbour, Antigua, Captain Middleton was left in charge of anti-privateering operations while Commodore Moore conducted amphibious landings against Martinique and Guadeloupe.

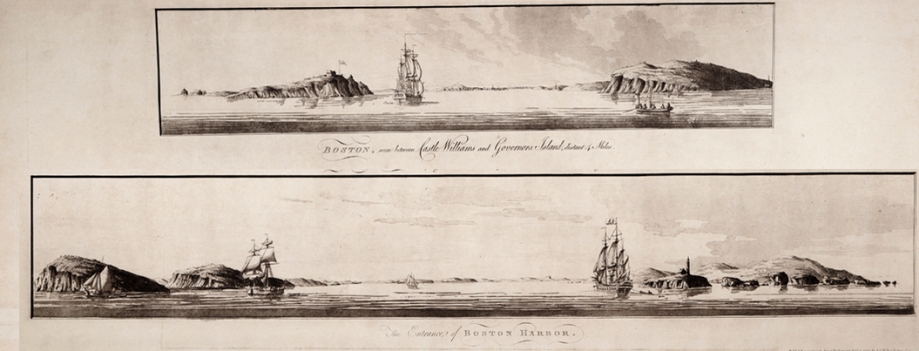

Plan of English Harbour, Antigua, 1782: base of operations for the Leeward Island station in 1758.

English Harbour in 1800, by Nicholas Pocock

Middleton, a natural administrator, thus oversaw trade as it massed at Antigua in preparation for its biannual convoy across the Atlantic. These large convoys, sailing at the beginning of June and July, of which the first, in June 1757, totalled 170 ships, were valued at least £2,000,000, and although fairly secure from interception, were generally uninsured. Individual merchant ships, however, not to mention the inter-island and coastal trade, indeed, were potential prey for French privateers sortieing from Guadeloupe and Martinique or crossing the Atlantic from the windward: over 1,400 trade ships were captured by French privateers in the West Indies over the course of the war.[xiv]

Order of battle for Leeward Islands and Jamaican stations, June 1757. Notice the significant increase in ships of the line attached to these two stations at this point. Middleton had been made Commander and appointed to the sloop HMS Speaker in February, a ship too small to be counted amongst the heavier warships, and thus does not appear on this list.

John Frazer’s painting of a frigate with full sail.

“Sloop” signed W. Van der velde, with English colours flying.<>

Captain Middleton thus found himself in a similar position to Captain Horatio Nelson, who, 27 years later, would likewise be appointed to Antigua and the Leeward Islands as a frigate commander.[xv] While captain of Barbados, in October 1758, Middleton wrote to a merchant representing the local chamber of commerce at St. Christopher’s (St. Kitt’s), regarding a proposed scheme for the defence of the islands. The plan involved two warships of 40 guns, two of 20 guns, and eight brigs of 16 guns, supported by two sloops of 10 guns each.[xvi] According to Middleton’s recommendations, these warships would be split between Barbados and Antigua, with two frigates stationed at each, and three brigs at the former, five brigs plus two sloops at the latter.

Nelson boards a captured ship, showing Nelson leaving HMS Lowestoft (32) to board a captured American privateer, 20 November 1777, by Richard Westall, 1806.

Captain Middleton’s detailed summary of the defence scheme identified what he believed to be the optimum arrangement for trade defence, observing that the area around Barbados could be relatively easily protected, although “…Antigua, St. Christopher’s, Nevis, Montserrat, Jamaica, &c.,” were more difficult to protect considering the numerous sailing routes between the islands.[xvii] In December 1759, writing from his new command, Arundel, Middleton believed the entire station could be covered by two ship of the line, four frigates, three brigs and two sloops, with reserves to relieve these forces as needed.[xviii]

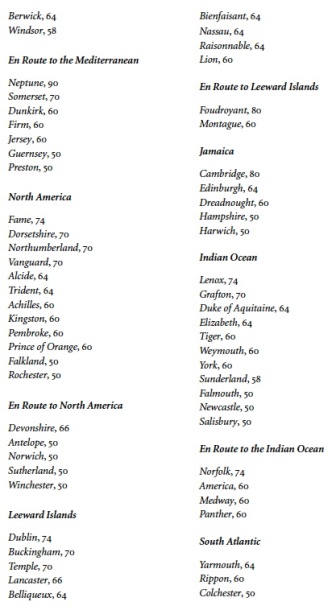

Leeward Islands and Jamaican commands, 1758, showing only four heavy warships on station at Commodore Moore’s station.

Middleton was keen to use the heavier frigates to cover the routes to and from Martinique, Marie-Galante and Guadeloupe, so as to interrupt French prize captures there. Middleton was executing a portion of Commodore Moore’s scheme, which, based on his predecessor, Rear-Admiral Frankland, involved the main squadron covering Martinique and the passage to Fort Royal and St. Pierre, capital of the French Lesser Antilles, while the various cruisers and frigates covered the islands and searched for privateers, of which, 25 were taken in the first ten months of Moore’s command, at least one of those by Middleton in the Barbados.[xix]

Leeward Islands and Jamaican commands, June 1759. Note the dramatic expansion in force, from four to 9 ships of the line, with three 60 and three 50 gun cruisers, made possible by the transfer of ships from the Louisbourg operation.

Rear-Admiral of the Blue, Sir John Moore, who, as Commodore, C-in-C Leeward Islands, oversaw the attack on Guadeloupe in January 1759.

Commodore Moore’s command had now been built up to ten ship of the line and 6,000 troops (under General Hopson) with which he might begin to capture the French island bases and thus solve the privateer problem at source.[xx] An attempt to storm Martinique on 16 January 1759 had been repulsed when it was discovered that the island’s defences were too strong.[xxi] Instead, the combined force mobilized against Guadeloupe, generating a siege that lasted until 1 May. The surrender of the island was accepted by Brigadier John Barrington, who had taken command following General Hopson’s death on 27 February.[xxii] The result of this series of events, which cost the French empire 80,000 hogsheads per anum in Guadeloupe sugar, prompted the dispatch of the Toulon squadron to the West Indies. French Admiral La Clue Sabran’s squadron, however, was intercepted as it left the Mediterranean by Admiral Boscawen (now C-in-C Mediterranean), with the result that five of the French ships were lost (of which, three were captured) at the Battle of Lagos, 18 – 19 August, 1759.[xxiii]

Battle of Lagos, of the coast of Portugal

ESA Envisat image of Guadeloupe, Dominica, and Martinique

View of Guadeloupe, William Wyllie, 1893

Invasion of Guadeloupe, January & February 1759, carried out by Commodore Moore

Guadeloupe captured, Peter Benezech’s engraving after Archibald Campbell’s view of Fort Royale, c. 1768

Detail of the assault on Basseterre, Guadeloupe. The siege lasted until the end of May 1759, the French relief fleet arriving too late to prevent the capitulation of the island.

Medal commemorating Commodore Moore’s capture of Guadeloupe, May 1759.

Middleton soon made Post-Captain, and in March 1759, while the Guadeloupe operation was under way, he was appointed commander of the 1746 vintage 6th rate frigate, HMS Arundel (24). Middleton, while cruising aboard the Arundel in November 1759, captured the slave transport Swift with more than 100 slaves on board. James Ramsay, Middleton’s assistant surgeon, and Middleton himself, were both appalled by the conditions onboard, confirming Middleton’s faith in abolition as the only just solution to the African slave trade. By December 1759, Captain Middleton had taken another four prizes, two merchants and two privateers, however, Arundel was in poor shape, with a damaged foremast, so Middleton returned to harbour.[xxiv] As Middleton built up the local flotillas, Commodore Moore was critiqued by the Barbados merchant committee for not bothering to intercept the French squadron sent to relieve Guadeloupe during the siege of spring 1759, with the result that “175 or 180 sail” had subsequently been captured and taken to Martinique, to be sold off at Fort Royal or St. Pierre, by the French.[xxv]

British (1, 5) and French (2, 3, 4) frigates, sloops and corvettes designed and built in the 1740s.

A heavy frigate, 5th rate

Captain Nelson’s HMS Boreas (28), built in 1774, with French frigate, by Nicholas Pocock.

A model of a 24 gun frigate built in 1741, similar to HMS Arundel, of 1746, the ship in which Captain Middleton made Post-Captain, in 1759. Note the hull ports close to the water line- for oars.

Plan of a 12 gun “Bermudan” pattern brig, the basic Caribbean corvette designed to out-weigh the French schooners and sloops. c. 1762.

Middleton continued to busy himself with flotilla outfitting and defence arrangements, repeatedly emphasizing the need for more “Bermudian” type brigs of 12 guns (such as HMS Speaker, Antigua, and Barbados) which, due to their armament and sailing qualities, he believed especially suited for the Leeward Islands. These heavy brigs were superior to the French sloops and schooners, the English brigs having captured 30 prizes on station by 1759.[xxvi] Middleton built off his predecessor’s layered defence scheme: as was the practice, convoys would handle the major cross-Atlantic trade, while local inter-island routes were best handled by brigs, or convoyed with frigates when available. Middleton argued for a flying detachment of two powerful frigates, or cruisers, stationed off Barbados, for actively hunting enemy privateers. Another group of frigates and sloops would provide a distant blockade of Martinique, thus surrounding the island’s traffic, a critical consideration with the Dutch trade at St. Eustatius effectively circumventing the blockade, if not intercepted.[xxvii]

In June 1760 there were three 70 gun ships of the line and five 64 gun cruisers on station, with reinforcements en route.

The coronation of George III in 1761 provided an opportunity for a change in strategy, with the Caribbean stations increasing in importance. William Pitt the Elder, who had directed British strategy as Secretary of State for the Southern Department while acting as Leader of the House, under the Duke of Newcastle (between June 1757 – 1761), was now displaced by the Earl of Bute, and resigned in October of that year. In July 1760, Middleton, replacing the gout-stricken Captain Cornwall, was given HMS Emerald (28), a prize taken in 1757, and it was in this ship that he secured his most profitable naval captures.[xxviii]

View of St. Pierre, Martinique, August 1796, by Cooper Willyams

June 1760

June 1761

Leeward Islands and Jamaican commands, June 1760 & 1761. By June 1761, the Leeward Islands station, where Captain Middleton was located, had four ships of the line, and eight heavy 64 & 50 gun cruisers, plus numerous lesser frigates and flotilla craft. Middleton returned to England in October 1761, at the same time, Admiral Rodney was despatched from England to orchestrate the capture of the French leewards.

Admiral George Rodney, after 1754. In 1761 he became the C-in-C Leeward Islands, and oversaw the capture of Martinique, St Lucia, Grenada and St Vincent.

As Middleton’s tour of duty at the Leeward Islands was coming to an end, Rear-Admiral George Rodney had been sent, in October 1761, to accelerate the campaign of seizure and capture of the French islands.[xxix] In January 1762, the year Britain declared war on Spain in response to the Spanish alliance with France, Rear-Admiral Rodney took 16,000 soldiers under Major-General Robert Monckton to Martinique, and captured the island by coup de main.[xxx] Rodney next dispatched Captain Augustus John Hervey in the Dragon (3rd rate) to St. Lucia, which Hervey proceeded to capture on 25 February 1762.

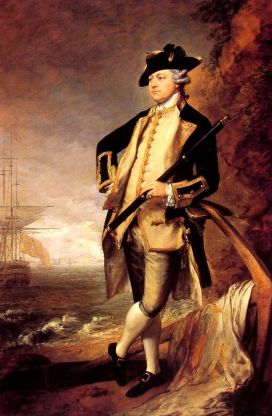

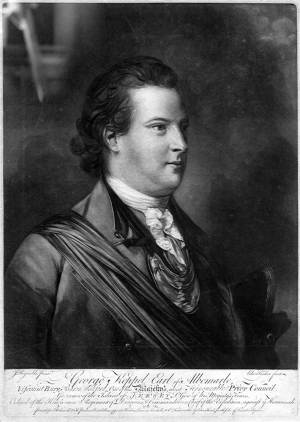

With Spain in the war, the next target was Havana. Rear-Admiral Sir George Pocock, and Lieutenant-General George Keppel, were dispatched from England with a fleet and 15,000 troops to break Spain’s Cuban fortress. Lord Anson, who had administered the Navy during much of the war, died in June 1762 and thus was unable to witness the successful capture of Havana in August of that year.

http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/13315.html

60 gun two deck ship of the line / cruiser, compared to a 24 gun frigate, at Gravesend, c. 1753-9, by Charles Brooking

The 66 gun heavy cruiser HMS Buckingham engaging French warships on 3 November 1758.

Caribbean fleets in June 1762, showing Havana invasion force.

Commodore Augustus Hervey, 3rd Earl of Bristol, c. 1767 by Thomas Gainsborough. Commodore Hervey captured St. Lucia as part of Rodney’s 1762 offensive.

Surrender of St. Lucia, February 25 1762, by Dominc Serres, 1772

Spain joins the coalition against Britain and Prussia. In 1762, Martinique, St. Lucia and Havana fall to the British.

The Capture of Havana:

Admiral Pocock’s fleet and amphibious task force arrived from England, and landed on 7 June 1762 to besiege Havana.

Rear-Admiral Sir George Pocock, who commanded the naval force at the Havana operation, painted by Thomas Hudson, c. 1761

Commodore Augustus Keppel, Lt. General George Keppel’s brother, and the second-in-command at Havana. Painted by Joshua Reynolds in 1749

Lt. General George Keppel, the Earl of Albremarle, who commanded the land forces at the Havana operation

The landing on 7 June 1762 of Lord Albermarle’s force against the Morro Castle fortress at Havana. Painting by Dominic Serres.

Capture of Havana, August 1762. This was the largest maritime operation of the war, requiring over 15,000 troops.

The fleet enters Havana on 21 August 1762, by Dominic Serres. Notice the distinct blue and red colours indicating squadrons and commands.

Middleton, meanwhile, had returned to England. Emerald was paid off in October 1761, to be broken up, its namesake uprated to a new 5th rate completed in 1762.[xxxi] Middleton had captured 16 prizes while captaining HMS Emerald, five of which were enemy privateers. During his four years in the Caribbean, Middleton had demonstrated an aptitude for trade defence, blockade, ship construction and fitting, discipline, and naval administration.

Full scale replica of the French 32 gun frigateFrench 32 gun frigate, Hermione, a ship similar to the 5th rate HMS Adventure (32), built in 1741 that was captained by Middleton in 1762. Seen here in June 2015 with USS Mitscher, an Arleigh Burke class DDG (guided missile destroyer).

As it turned out, in March of 1762, Middleton was appointed Captain of HMS Adventure (32 – a different ship from the Adventure which became Captain James Cook’s second alongside Resolution in 1771), a fifth rate which had been recut from a fourth rate in 1758. Captain Middleton was sent to patrol along the Channel and Normandy coast.

Map showing British strategy and territories secured during the Seven Years’ War, from Paul Kennedy’s Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery.

Map showing major colonial empires after the Treaty of Paris.<http://www.worldmapsonline.com/images/Cram/History/colonialempires1763.jpg>

The Treaty of Paris, which ended the Seven Years’ War, was signed on 10 February 1763, and as part of the negotiations, Guadeloupe, St. Lucia and Martinique, the former captured in 1759 and the latter two in 1762 respectively, were returned to France; Canada, however, was ceded to Great Britain. Havana and Manila, both taken from Spain, were likewise returned, in exchange for Florida and Minorca.[xxxii]

Deptford dockyard, 1763 by John Cleveley the Elder

Middleton went on half-pay until March 1762. In December 1761, at the age of 35, Charles Middleton married Margaret Gambier, a skilled painter and later an advocate for the abolition of slavery. Margaret was the daughter of Captain James Gambier, to whom Middleton was familiar through the connection of Captain Mead, whose sister, Mary, was Margaret’s mother. Middleton had first served with Mead during their time aboard the Sandwich, twenty years prior. Margaret gave birth to their only child, a daughter, Diana, on 18 September 1762.

Family of Margaret Gambier, who became Mrs. Middleton in December 1761.

Middleton, for his part, retired from the service, declining a sea-going appointment on 2 April 1763, to retreat to the hospitality of his wife, then living with her friend Elizabeth Bouverie, at Teston, in Kent.[xxxiii] Margaret and Elizabeth were joined there after 1777 by Captain Middleton’s former assistant surgeon from the Arundel, now a staunch abolitionist and priest, James Ramsay, who became a close friend of Mrs. Middleton and her circle, as well as private secretary to Charles, drafting many of his letters.[xxxiv] It was the wealthy Elizabeth Bouverie, proprietor of Barham Court, who, upon her death in 1798, left to Charles Middleton the entire Teston estate, the source of his title as Lord Barham.

Recent photographs of Barham Court, Teston, Kent.

The Mall at St. James Park, by Thomas Gainsborough, 1782. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Gainsborough#

View of the Temple of Comus in Vauxhall Gardens by Canaletto circa 1750s, engraved by Johann Muller

Warships fitting out at Portsmouth, 1770, by Dominic Serres.

Comptroller & the American Revolution

Middleton remained in these pleasant surroundings for twelve years, until, with the American Revolution underway, he joined HMS Ardent (64) in May 1775. Much as his efforts during the Caribbean operations had focused Middleton on administrative duties, he soon found himself running Chatham dockyard as Commodore Mackenzie’s assistant, and by December 1775, was in communication with Lord Sandwich regarding ship fittings, among other dockyard matters.[xxxv] Middleton was writing his own standing orders by this point, his orders for Ardent focusing on proper logistics, discipline, gunnery, and duties.[xxxvi] On 7 November 1776, Middleton was made Captain of HMS Prince George (90), a new but decommissioned second rate built in 1772.

Middleton was working this ship up for more than a year- one imagines Middleton regularly visiting the dockyard during 1777- until February 1778 when he was transferred to the 4th rate Jupiter (50), then under construction. Middleton was back on half-pay on 22 July 1778, then, the next month, following the death of Comptroller Captain Maurice Suckling, Middleton was appointed Comptroller of the Navy by his friend, the First Lord of the Admiralty, John Montagu, the 4th Earl of Sandwich.[xxxvii] Middleton would be in this position for twelve years, until he resigned in 1790.

Jupiter, 1778, 50 guns, 4th rate, plans by John Williams, Navy Surveyor

John Montagu, the 4th Earl of Sandwich in 1774, by Valentine Green, after Johan Joseph Zoffany.

View of Leicester Square by Thomas Bowles, circa 1753

The Earl Sandwich was one amongst a powerful circle of Middleton’s friends, including Middleton’s cousin, Henry Dundas, the Lord Melville, then the Lord Advocate of Scotland, and George Germain, Secretary of State for America, who, together with Lord North, would fail to contain the American Revolution in years to come. Middleton kept up a regular correspondence with Admiral Hood and Captains Young and Kempenfelt, who provided the Comptroller with intelligence and a brain-trust to work out signalling tactics or new construction ideas. Middleton’s marriage into the Gambier family further increased the reach of his network, as his brother-in-law was Vice-Admiral James Gambier, C-in-C North America. Lady Middleton herself, highly respected by British society, was friends with Samuel Johnson and James Boswell, amongst other men and women of letters.[xxxviii]

Admiral Samuel Hood’s victory at St. Kitts, 25 January 1782. Hood kept Middleton informed about developments in the Caribbean via a detailed letter correspondence.

Admiral Sir Samuel Hood, with whom Middleton kept a regular correspondence during the American Revolutionary War.

The devout and ascendant Middleton, soon Lord Commissioner, then First Lord of the Admiralty, and Baronet Barham after 23 October 1781, was occasionally at odds with his benefactor, Sandwich. As Comptroller, Middleton was responsible for the statistical control of Navy’s dockyards, warships and naval supply, as this information was collected by the Admiralty’s various accountants. Middleton mastered the naval supply accounts and advanced his schemes for improvement, such as roofing all of the dockyards- a difficult task not completed until the following century.[xxxix] Minorca was retaken on his watch on 4 February 1782.[xl] Wartime policy occasionally led to cut corners, however, as demonstrated by Sandwich’s efforts to provide copper sheathing to all the warships of the fleet. It was Middleton’s budget method that produced the electrolytic action that pre-naturally aged the fleet’s warships, which resulted in several significant defects (contributing to the losses of HMS Terrible and Royal George).[xli] The fleet was eventually re-coppered at considerable expense, with specially coated copper nails, effectively the French method of copper construction.[xlii]

Admiral Rodney’s victory at the Saints, off Dominica, 12 April 1782. George Rodney’s spectacular defeat of the Comte de Grasse was too late to reverse the outcome of the American Revolution, although it evened the naval scales.

Barham as Comptroller of the Navy in 1788.

As a result of his incessant centralizing drive for reform, Middleton’s later career was not without its antagonists: the Viscount Howe, Admiralty First Lord from 1783 until 1788- who Middleton had worked with under Boscawen in 1755- had opposed Middleton’s reforms. Middleton and Sandwich eventually fell out as well, nevertheless, the Middleton – Sandwich administration, despite its travails and failures, would be remembered as one of those dynamic Admiralty leadership combinations that so infrequently graced the office of state, comparable perhaps only to Sir John Fisher and Winston Churchill in 1914, or Francis Drake and Admiral Sir John Hawkins in 1588.[xliii]

Portrait of the Earl Richard Howe, commemorating his victory at the Glorious First of June, 1794.

Middleton was elected MP (Tory) for Rochester in 1784 – 1790, and made Rear-Admiral of the Red on 24 September 1787. Together with his old friend James Ramsay, and Lady Middleton’s associate William Wilberforce MP, Middleton advocated for the abolition of slavery and the slave trade, of which he had seen the worst of during his naval career. Middleton, during this time, defeated his erstwhile opponent Lord Howe, who was superseded by the brother Pitt, John, the Earl of Chatham, on 16 July 1788. Middleton was long frustrated in his efforts to get himself onto the Admiralty Board, however, and he resigned in March 1790. Margaret, Lady Middleton, died two years later, on 10 October 1792, and Charles was left with Diana and her husband Gerard. Middleton was made Vice-Admiral in February 1793, then, his wish was granted in 1794, and he joined the Admiralty as First Naval Lord, aside Lord Spencer, until November 1795. He made full Admiral of the Blue in 1795.[xliv] Middleton was out of the loop, however, as the Admiralty was under the control of another of Middleton’s antagonists, Admiral Sir John Jervis (presently, after his victory in February 1797, the Earl St. Vincent), First Lord of the Admiralty in 1801.

Portrait of Admiral Sir John Jervis, the Earl St. Vincent, by William Beechey, c. 1787-90

Rhineback panorama of London in 1806

The Admiralty, February 1795 by Thomas Malton, jr.

It was the intervention, at this point, of Middleton’s friend, the leader of the “new Tories”, William Pitt the Younger, who returned him to power. Middleton was appointed chairman of the Commission for Revising, a naval budgetary control organization established in December 1804, not long after the Earl St. Vincent’s departure the preceding year (“that damned Scotch packhorse” Admiral John Jervis called Middleton).[xlv] Henry Dundas, the Viscount Melville, then the First Lord, was out by May 1805 and Pitt asked Middleton to succeed him.[xlvi]

William Pitt, the Younger, by John Hoppner, 1805

An important consideration was any successor’s ability to work with Vice-Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson of the Nile. Middleton had first met Nelson in November 1787, and Nelson had found in Middleton a kindred reformer. Although separated by more than two decades, they had served on the same station as frigate commanders, and had corresponded during the American Revolutionary War.[xlvii]

Vice-Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson of the Nile, 1800, by Friedrich Fuger

Like Nelson, an evangelical man, Middleton was distraught by the heavy-handedness of St. Vincent’s reforms; not to mention his military mistakes. Knowing a sure thing when he saw it, Pitt appointed Middleton as First Lord, his status in the peerage raised to 1st Baron Barham of Barham Court and Teston, Kent, with Admiral James Gambier (Margaret’s nephew), the Baron Gambier, as First Sea Lord.[xlviii]

Admiral James Gambier, Baron Gambier, sketch by Joseph Slater, 1813

Middleton dispatched Nelson reinforcements, and tightened the Channel blockade in the lead up to Trafalgar,[xlix] and afterward Middleton was made full Admiral of the Red on 9 November 1805. Known for their proficiency with ship design, and defensive mindset, Gambier and Middleton introduced the revised Naval Regulations of 1806.[l] With Nelson deified, and Pitt soon to follow, at eighty years old, Charles Middleton retired for the last time 1806.[li] The Lord Barham, Admiral of the Red Sir Charles Middleton, Comptroller of the Navy during the American Revolutionary War, Senior Naval Lord during the French Revolution, and First Lord of the Admiralty during Trafalgar, frigate commander in the Leeward Islands during the Seven Years War, died on 17 June 1813, at the age of 87.

Isaac Pocock’s portrait of Admiral Sir Charles Middleton, the Lord Barham.

Middleton’s legacy is as a farsighted reformer and modernizer, at once pragmatic and controversial. As First Lord of the Admiralty, he established the position of First Sea Lord as the chief naval post on the Board, thus setting the pattern for the 19th and 20th centuries.[lii] A relentless modernizer, yet a devout Tory; a disciplinarian who opposed slavery, Middleton’s career certainly possessed its share of conflicts. Details about Middleton’s important administrative career during three wars can be found in a number of sources, although the modern researcher will not find a better one than Sir John Knox Laughton’s three volumes of the Barham papers, published shortly before the First World War, by the Navy Records Society.[liii]

Barham was established as a Royal Navy ship name, starting with the 74 gun 3rd rate in 1811 (modified to 50 guns in 1826).

HMS Barham (50) at Sheerness, in February 1836, by Francis Byron

An HMS Barham screw frigate was ordered for 1860, however the order was canceled.

The name was next given to an ironclad cruiser in 1889, which was sold off in February 1914, as, on 31 December of that year, the name was recycled into HMS Barham.

HMS Barham was a 27,500 ton Queen Elizabeth class oil-fuel super-dreadnought built and commissioned between February 1913 and October 1915. Beginning on 1 October 1915, HMS Barham, commanded by Captain Arthur W. Craig, became the flagship of the 5th Battle Squadron, led by Rear-Admiral Evan Thomas, and fought at the Battle of Jutland on 31 May 1916. 25 years later Barham was at the Battle of Matapan, in March 1941. The warship was finally torpedoed, with the loss of most of the crew, by U-331, commanded by Kptlt. Hans-Diedrich Freiherr von Tiesenhausen, on 25 November 1941.

HMS Victory is towed into Portsmouth Harbour in preparation for preservation, December 1921. HMS Thunderer and Barham, docked in line-ahead on the left, by William Wyllie.<http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/15173.html>

[i] N. A. M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2006)., p. 373

[ii] N. A. M. Rodger, The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy (London: Fontana Press, 1988)., p. 212-14

[iii] John Talbott, The Pen & Ink Sailor: Charles Middleton and the King’s Navy 1778 – 1813, Kindle (Frank Cass Publishers, 1998)., chapter 1.

[iv] John Knox Laughton and R. Vesey Hamilton, The Barham Papers, Volume I, digital, vol. 1, 3 vols., Navy Records Society 32, 1906., p. xii-xiii

[v] Roger Morriss, “Middleton, Charles, First Baron Barham (1726-1813),” The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

[vi] Talbott, The Pen & Ink Sailor: Charles Middleton and the King’s Navy 1778 – 1813., chapter 1.

[vii] Clevland to Hawke, 11 March 1755, #88, Ruddock Mackay, ed., The Hawke Papers, A Selection: 1743 – 1771, Navy Records Society 129 (Aldershot, Hants: Scolar Press, 1990). p. 117 fn

[viii] Laughton and Hamilton, The Barham Papers, Volume I., p. xiv

[ix] Julian Corbett, The Seven Years War, A Study in British Combined Strategy (London: The Folio Society, 2001)., p. 41; Rodger, The Command of the Ocean., p. 263; A. T. Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660 – 1783 (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1987)., p. 284

[x] John B. Hattendorf, “The Struggle with France, 1689 – 1815,” in The Oxford Illustrated History of the Royal Navy, ed. J. R. Hill and Bryan Ranft (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 80–119., p. 96-7

[xi] Corbett, The Seven Years War, A Study in British Combined Strategy., p. 268-9

[xii] Ibid., p. 272

[xiii] Laughton and Hamilton, The Barham Papers, Volume I., p. xvi

[xiv] Corbett, The Seven Years War, A Study in British Combined Strategy., p. 267-8; Rodger, The Command of the Ocean., p. 277

[xv] John Sugden, Nelson: A Dream of Glory, vol. 1, 2 vols. (London: Pimlico, 2005)., p. 244

[xvi] Middleton to Mr. Walter Pringle, 21 October 1758, Laughton and Hamilton, The Barham Papers, Volume I., p. 1-2

[xvii] Middleton to Mr. Walter Pringle, 21 October 1758, Ibid., p. 3

[xviii] Middleton to Pringle, 4 December 1759, Laughton and Hamilton, The Barham Papers, Volume I., p. 16

[xix] Corbett, The Seven Years War, A Study in British Combined Strategy., p. 278; Middleton to Mr. Walter Pringle, 21 October 1758, Laughton and Hamilton, The Barham Papers, Volume I., p. 7

[xx] Rodger, The Command of the Ocean., p. 277

[xxi] Ibid., p. 277

[xxii] Ibid., p. 277

[xxiii] Ibid., p. 277-8

[xxiv] Middleton to Pringle, 4 December 1759, Laughton and Hamilton, The Barham Papers, Volume I., p. 17

[xxv] Council and Merchants of Barbados to Joseph Pickering, 1759. Laughton and Hamilton, The Barham Papers, Volume I., p. 21-2

[xxvi] Middleton to Pringle, 1759, Laughton and Hamilton, The Barham Papers, Volume I., p. 18

[xxvii] Middleton to Sir James Douglas, 1760, Laughton and Hamilton, The Barham Papers, Volume I., p. 32

[xxviii] Laughton and Hamilton, The Barham Papers, Volume I., p. x, Rodger, The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy., p. 103

[xxix] Anson to Rodney, 5 October 1761, #846 in David Syrett, ed., The Rodney Papers, Volume I, 1742 – 1763, Navy Records Society 148 (Aldershot, Hants: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2005)., p. 422

[xxx] Rodger, The Command of the Ocean., p. 284

[xxxi] Lieutenant’s Logs, Navy Board, HMS Emerald, 1758 – 1760, ADM/L/E/96, http://collections.rmg.co.uk/archive/objects/526873.html ; T. D. Manning and C. F. Walker, British Warship Names (London: Putnam, 1959).

[xxxii] Rodger, The Command of the Ocean., p. 287-8

[xxxiii] Morriss, “Middleton, Charles, First Baron Barham (1726-1813).”

[xxxiv] Laughton and Hamilton, The Barham Papers, Volume I., p. 46

[xxxv] Middleton to Lord Sandwich, 1 December 1775, G. R. Barnes and J. H. Owen, eds., The Sandwich Papers, Vol. I., August 1770 – March 1778, vol. 1, Navy Records Society 69 (Navy Records Society, 1932). p. 78

[xxxvi] Captain’s Order Book, 1 August 1775, Laughton and Hamilton, The Barham Papers, Volume I., p. 39

[xxxvii] Laughton and Hamilton, The Barham Papers, Volume I., p. x

[xxxviii] http://www.thepeerage.com/p5349.htm#i53488

[xxxix] Ibid., 376

[xl] Laughton and Hamilton, The Barham Papers, Volume I., p. xxxv

[xli] Rodger, The Command of the Ocean., 375-6

[xlii] Ibid., 374-5

[xliii] Arthur Herman, To Rule the Waves (New York: HarperCollins Publishers Inc., 2004)., p. 316

[xliv] Roger Knight, Britain Against Napoleon: The Organization of Victory, 1793 – 1815 (St Ives plc: Penguin Books, 2014)., p. xix-xx

[xlv] Talbott, The Pen & Ink Sailor: Charles Middleton and the King’s Navy 1778 – 1813.

[xlvi] Rodger, The Command of the Ocean., p. 480

[xlvii] Sugden, Nelson: A Dream of Glory., p. 370-1

[xlviii] Andrew Lambert, Admirals (London: Faber and Faber Limited, 2009)., p. 180-1; Herman, To Rule the Waves. p. 336, 369; John Sugden, Nelson: The Sword of Albion, vol. 2, 2 vols. (London: The Bodley Head, 2012)., p. 761-5

[xlix] Sugden, Nelson: The Sword of Albion., p. 785-6

[l] Richard Blake, “James Gambier, Baron Gambier (1723-1789),” The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

[li] http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/100697.html

[lii] Rodger, The Command of the Ocean., 480

[liii] Sydney Riddick, “Charles Middleton, Afterward Lord Barham, and Naval Administration, 1778-1805” (MA Thesis, Liverpool University, 1939).; H. C. Fox, “A Discussion of the Problems of Naval Administration Arising from the Period Covered by ‘The Barham Papers.,’” Naval Review, no. 4 (1935): 758. ; Talbott, The Pen & Ink Sailor: Charles Middleton and the King’s Navy 1778 – 1813.; Laughton and Hamilton, The Barham Papers, Volume I.; John Knox Laughton, The Barham Papers, Volume II, digital, vol. 2, 3 vols., Navy Records Society 38, 1910.; John Knox Laughton, The Barham Papers, Volume III, digital, vol. 3, 3 vols., Navy Records Society 39, 1911.

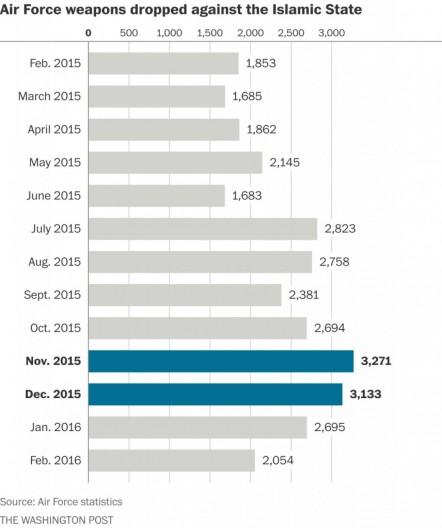

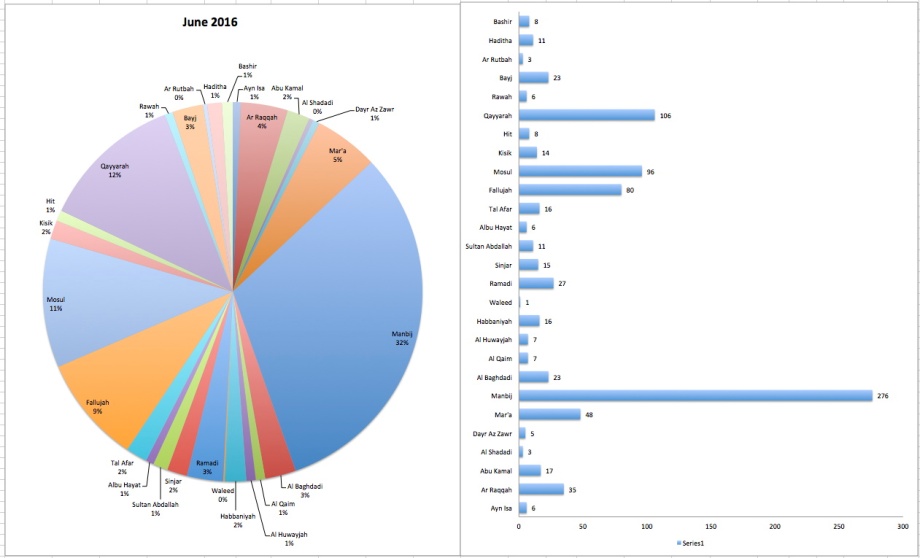

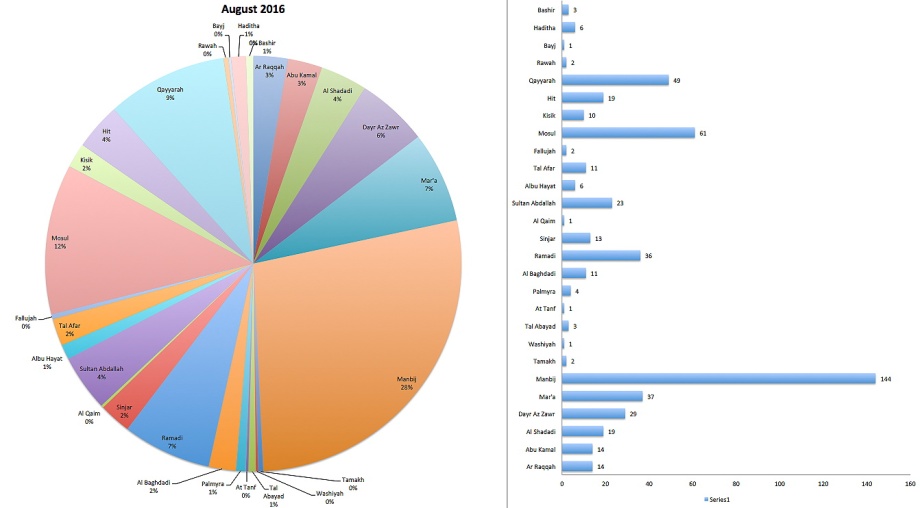

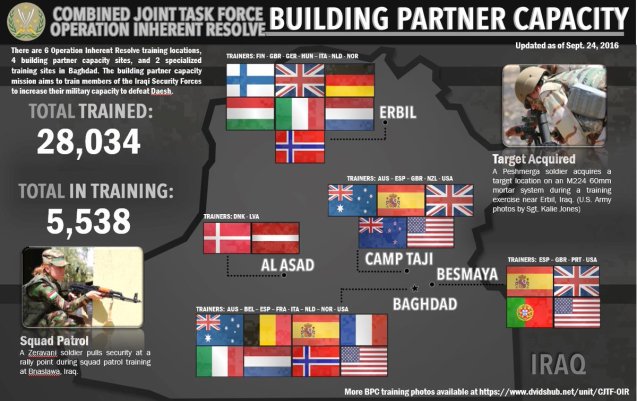

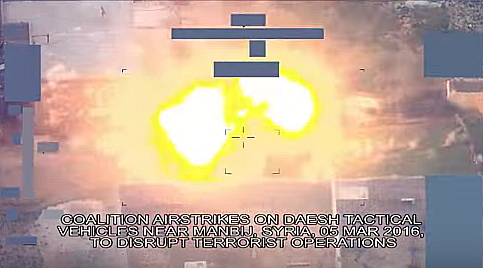

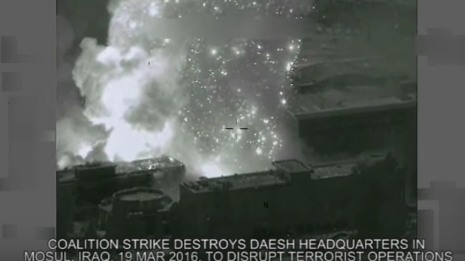

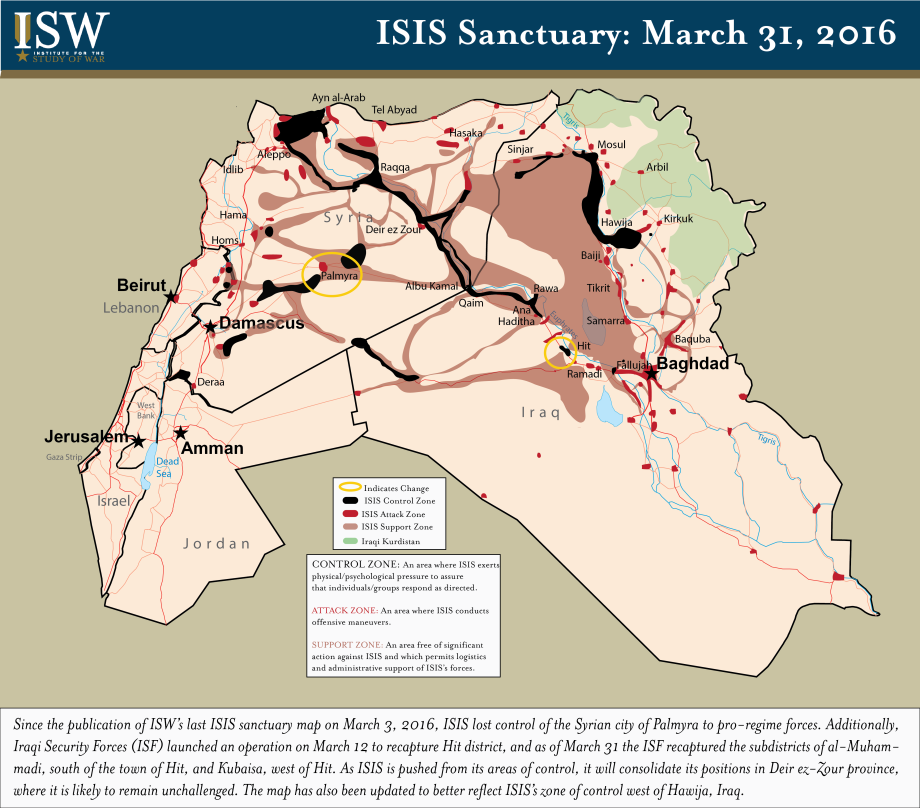

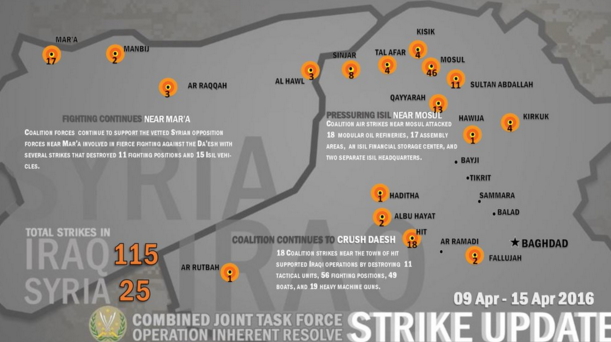

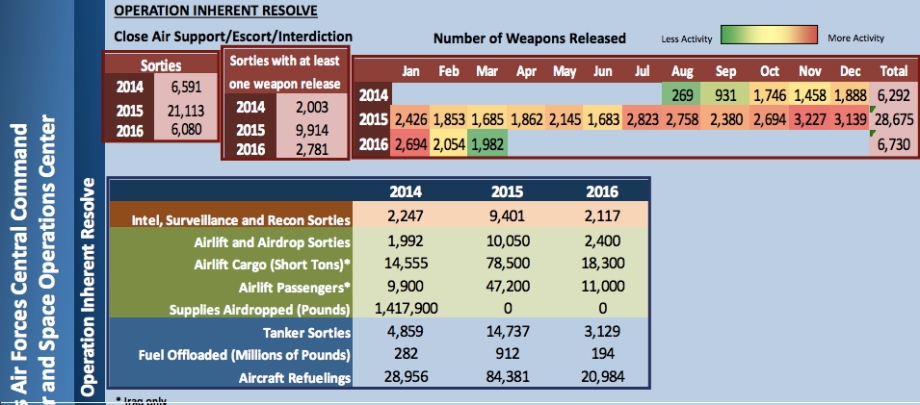

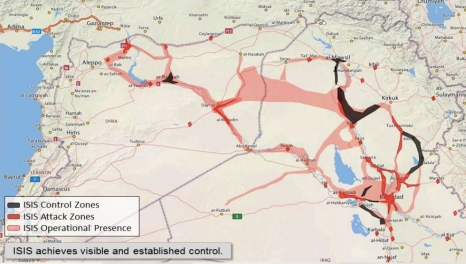

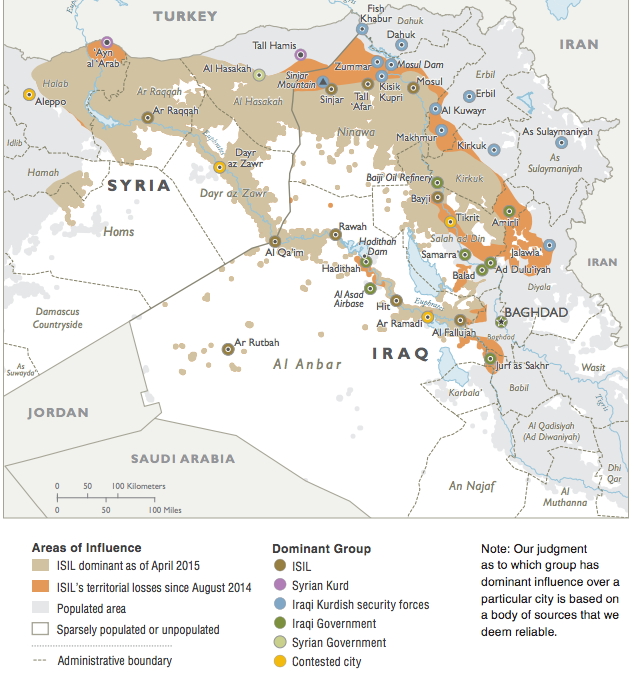

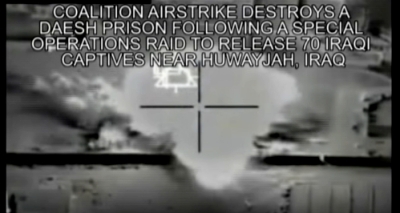

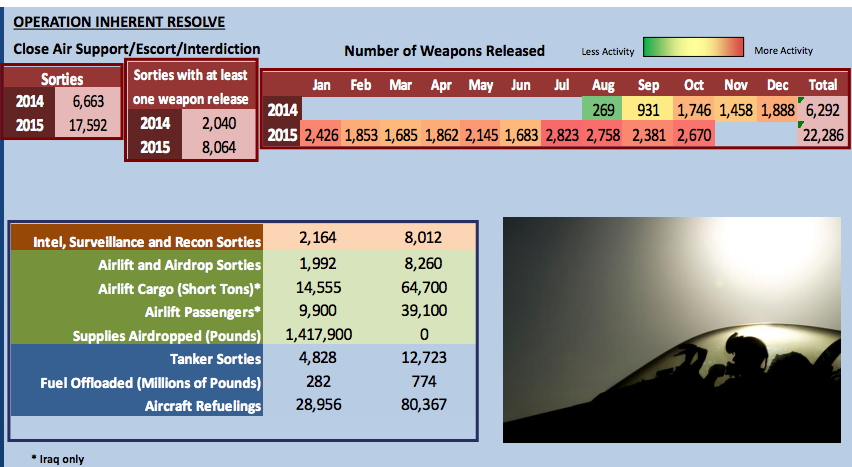

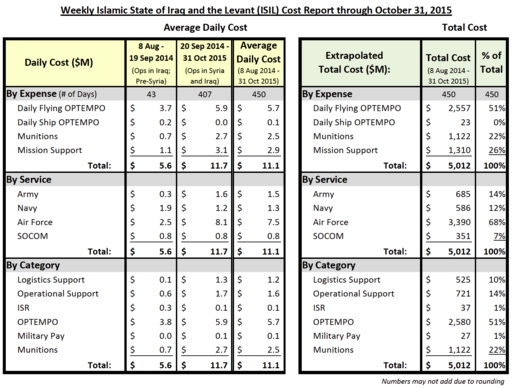

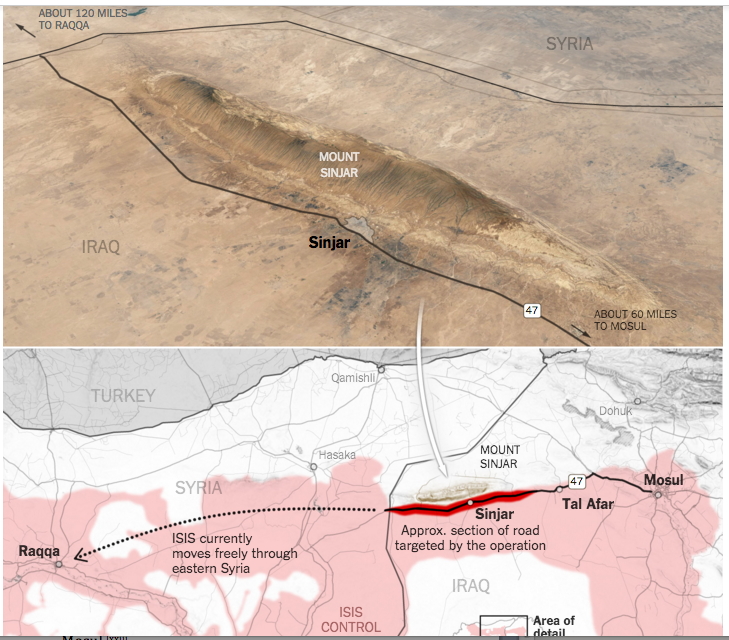

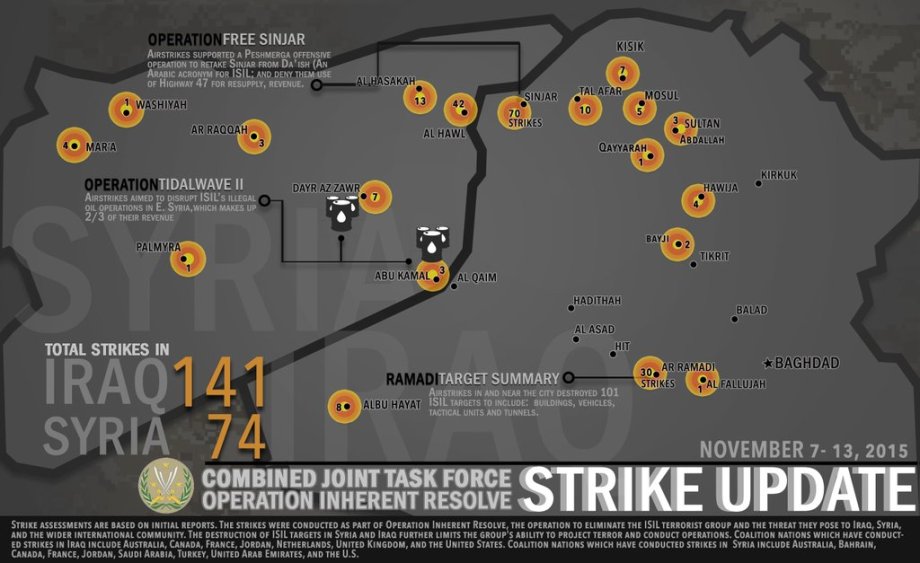

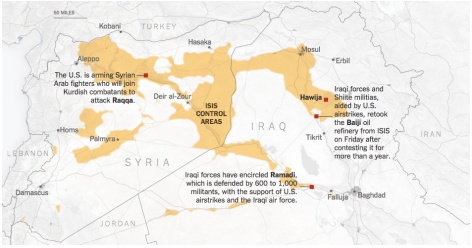

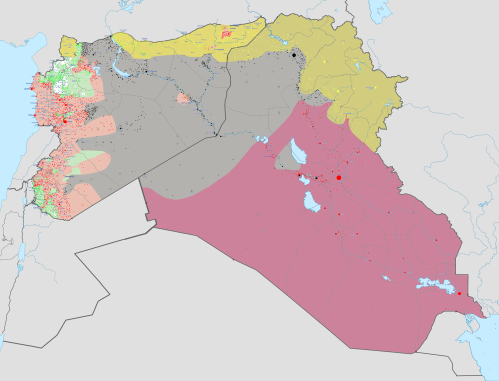

August 8th, Operation Inherent Resolve commences.

August 8th, Operation Inherent Resolve commences.

![militaria-cavalry-v-archers.-battle-of-crecy.-1894-wdjb--135735-p[ekm]400x243[ekm]](https://airspacehistorian.files.wordpress.com/2015/01/militaria-cavalry-v-archers-battle-of-crecy-1894-wdjb-135735-pekm400x243ekm.jpg?w=920)